By Alexander Ekemenah, Chief Analyst NEXTMONEY

Introduction

The much expected military coup in Sudan has finally happened precisely a month after a failed attempt to overthrow the Sudan interim government headed by Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. For many keen watchers of the Sudanese politics in the last six months, if not more than this, this coup could not have come as a surprise at all. What may have come as a surprise is perhaps the lightning speed with which events unfolded and climaxed into the coup especially after the failed coup attempt on September 21, 2021.

In the early hours of October 25, a month after the failed coup attempt, the military struck again, arresting Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and his wife and putting them under lock and key in a house arrest in Khartoum including other high government civilian officials. The entire Sovereign Council and/or the Transitional Council was sacked and dissolved. The new military strongman, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan who was hitherto the head of the Sovereign Council and the de facto President made a broadcast to the nation announcing the dissolution of the interim government under the pretext of maintaining law and order and preventing chaos from swallowing up the country.

Al-Burhan declared a state of emergency, explaining that the military needed to protect the country’s safety and security. “We guarantee the armed forces’ commitment to completing the democratic transition until we hand over to a civilian elected government,” he said. “What the country is going through now is a real threat and danger to the dreams of the youth and the hopes of the nation.” In short, the coup was hatched and executed to protect the national security interests of Sudan – as defined by General al-Burhan and/or his military faction within the Sovereign Council.

What was surprising about the coup is that nobody had expected that the coup would happen so soon after the failed attempt on September 21. This, however, merely shows the tempest that has been raging within the bowel of Sudan in the last several months and the desperation of the coup plotters to oust the transitional government and grab power for themselves.

The Western governments were also probably caught by surprise especially the United States who’s Envoy to the Horn of Africa, Mr. Jeffrey Feltham, had earlier held a meeting with the warring groups in the early hours of the day in an attempt to diffuse the rising tension. Shortly after his departure from Sudan, General al-Burhan and his henchmen rolled out the armoured tanks and big guns to carry out the coup. The gunpowder barrel has finally exploded. It could be certain that the US did not see the coming of the coup at that point in time.

Nobody also knows that the green snake living under the green grass was none other than the head of the Sovereign Council, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, himself. This was not a coup from the middle-ranking soldiers, from below the military hierarchy that could have possibly swept out the Generals from their command posts. It is rather a coup by the Generals themselves, from the very top-echelon command of the military establishment. The Sovereign Council, cobbled together in August 2019 as a hybrid contraption, was the diarchic system of shared power between the military and civilians in a transition government that was assigned the main duty of supervising the transitional process towards election in 2023 that is expected to lead to democratic rule. The Transitional Military Council that was established in April 2019 after Omar al-Bashir was kicked out and which preceded the Sovereign Council was rejected by the Sudanese. Interestingly, since 2019, there has been no central electoral body and/or system on ground to start preparing for the general elections expected in early 2023 as the culmination of the transition process. There is no known election time-table anywhere to be seen. There is no voters’ registration exercise embarked upon at any point in time since the interim government was put in place in August 2019.

But a careful sorting out of facts would reveal that General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan has been publicly posturing and speaking body language that can only be interpreted to only mean that he does not like the contraption called Sovereign Council of which he was the head; and that he wants to rule unchallenged and to be able to call all the shots across the full political spectrum. Al-Burhan has been travelling overseas a lot, secretly garnering strategic contacts, publicity and other appurtenant of power. He has clearly demonstrated beyond all reasonable doubts that he is another Omar al-Bashir in the making. Only the unwary will not see this trend that has clearly established itself in the last couple of months in Sudan before the jackboot of the military finally came matching down on the Sovereign Council.

Right from the very beginning, there is no doubt that this diarchic system is bound to fail altogether because of its essential character flaw. Packing wolves and sheep together in a room or “Council” is bound to fail inevitably and in a miserable manner as the civilian preys are being pounced upon and devoured by the hungry military predators. The civilian sheep could only be heard bleating loudly while they were been torn apart by the pack of ferocious wolves sequestered among them. It was not only a huge strategic error but also a very sickening joke.

The situation was similar to what happened in Nigeria in August 1993 when an Interim National Government was hastily set up by the departing Ibrahim Babangida-led military dictatorship. The ING was headed by Chief Ernest Shodeinde Shonekan. The ING included General Sani Abacha who was expected to give a “military muscle” to the ING. On November 17, 1993, it was precisely General Sani Abacha that kicked out Chief Ernest Shodeinde Shonekan, dissolved the ING and subsequently embarked upon a full-blown military dictatorship, the type that has never been witnessed in the Nigerian political history.

The coup has thrown Sudan into another round of crisis that nobody can foresee how it will end. Sudan is consequently standing at an inflection point in its evolution as a Nation-State. Sudan has become an existential threat to itself. While the coup has been overwhelmingly condemned by the international community coupled with loud street protests including killing of protesters by the soldiers, the new military junta has dug itself into power and is not willing to relinquish it by any means. The fumbling and bungling of peace process are coming at a huge cost. All investment in the peaceful resolution of the raging crisis is being seen as a waste.

Since the overthrow of Omar al-Bashir in 2019, Sudan has been roiling and rolling from one crisis to another notably amidst economic crisis. Sudan has almost devolved into a Hobbesian state of nature: brutish, nasty and short, where dog eat dog! The political instability and coupled with the economic crisis that Sudan have had for a long time may have actually pushed the Sudan State to the verge of State collapse. There is a sense in which Sudan can indeed be argued to be a failed state already even with the existence of the Sovereign Council with whatever achievements have been ascribed to it since 2019 when it came into being. This is premised on the inability of the State to protect its citizens from socioeconomic vagaries of insecurity and ethnic-based clashes. The State, through the armed forces and paramilitary forces, that is statutorily and primarily responsible for the protection and safety of the citizens have ended up mowing down the same citizens on the streets of Sudan.

Sudan is now in the eyes of crossfire, caught between anti-democratic and pro-democratic forces thus turning Sudan into a geopolitical or geostrategic battleground between various global power blocs (certain Middle East countries – Egypt, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates – including Iran, Turkey; Russia and China on the one hand and Western countries including African Union on the other hand). It is a situation akin to being caught on a horn of a dilemma, about to be flung by the bull of the dilemma if it does not quickly find a way to dismount from the bull. Sudan has become a playing ground for all manners of players. The Middle East countries (Egypt, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates in particular) are still mortally afraid of the haunting ghosts of Arab Spring and do not want to see Sudan as a new bridgehead of democratic rule in the Horn of Africa/East Africa being the largest country in Africa in terms of land mass even though with a meagre demographic strength of about 42 million people. There are also countries like Iran and Turkey with their different agendas. So also are the positions of China and Russia that can be clearly discerned as far as their ideological and foreign policy thrusts are concerned in relation to the United States and other Western European powers. United States and several other Western European countries on the other hand clearly want to see Sudan joining the ranks of democratically-ruled countries in Africa and the world under their sphere of influence. However, nobody is exactly certain of the position of African Union – a rather unfortunate situation.

There is no doubt that a democratic Sudan will have enormous geopolitical impacts in the Horn of Africa. The echoes of its democratic regime will be far-reaching even beyond the immediate region, most probably reaching the Gulf of Aden and the Middle East in general. It is the possibility of this democratic rule being established in Sudan (by 2023) that has largely attracted Western countries which has manifested by the US dolling out $700 million for the transition programmes which has however been withheld until normalcy returns to Sudan. It is this possibility of democratic rule that has also become a source of mortal fear both for the reactionary Sudanese military and its Middle East backers.

Thus there is the sense in which the unfolding crisis in Sudan can be seen and regarded as an archetypal political clash between Sudanese Generals (the Old Guard trying to defend and safeguard the Old Order encapsulated in the interests of Omar al-Bashir-led National Congress Party on the one hand and the mass of the people whose political consciousness or social awareness has been raised to the highest level by events of the last few years who are now rooting for liberal democracy supported by several Western countries such as the United States on the other hand. It is not so much of a civilizational clash (though very close to it) between certain Middle East countries and their other allies that do not want to see democracy sprouting in Sudan and the Western countries that want to see democracy growing and sustainable in the country. It may be interesting to note that even though the majority of the populace is Muslim, they have, however, rejected political Islamism as represented by Hassan el-Turabi and Omar al-Bashir’ National Congress Party (the dominant Islamic party in Sudan). Of course it is a fierce battle for supremacy between the two different and opposing ideological camps and their worldviews – between political Islamism and Western political liberalism. That is why the Middle East countries are in full support of the military Junkers in Sudan because they are mostly Islamists who are susceptible to threading the path of fundamentalism with all the well-known historical and/or contemporary effects.

This is the broad or panoramic context in which the latest crisis occasioned by the October Coup can be viewed and analyzed in order to bring out its overt strategic implications and subtle nuances.

Statement of the Problem

The Sudanese crisis is more of a crisis of State legitimacy than anything else because of its current diarchic arrangement and character of the transitional government. The Sudanese State is highly suspected not to be performing its main statutory functions of security and welfare of the citizens but only seen to be keeping certain men (and women) power for its own stake. This crisis is historical in origin. The Sudanese State has long ago delegitimized itself by its gross inability to function as a modern State characterized and driven by rule of law and respect for fundamental human rights of its citizens in its governance landscape.

This history started with Omar al-Bashir, if not during the time of Jafaar Numeiri. Of all the post-Independence Sudanese leaders, Omar al-Bashir is perhaps the most prominent. He bestrode Sudan like a colossus. But he ruled Sudan with unparalleled iron fist to his satisfaction and succeeded in bringing the country to its knees, to the lowest depth. Sudan was already practically at the precipice of complete collapse by the time al-Bashir was toppled on April 11, 2019 and later hounded to imprisonment. The same forces that raised him and sustained him in power for almost three decades finally turned against him, threw him out of the Presidential Palace and into Kobar jail.

Omar al-Bashir though much liked by the militants had however become a heavy liability to Sudan. South Sudan has already broken away eight years earlier in May 2011 under his watch and clumsy authoritarian hands. Al-Bashir was increasingly imperiling Sudan. It is better for Omar al-Bashir to be sacrificed than for the whole Sudan or its military to disintegrate or be brought to total public disrepute. It is better for one man to die than for the whole nation to perish – in accordance with the biblical Caiaphas Principle! This was the fundamental axiom upon which he was finally removed and dumped into jail.

The Western governments, especially the United States were up in arms against Sudan for sponsoring global terrorism and harboring well-known international terrorists. The United States imposed all sorts of sanctions which bit hard at Sudan. But Omar al-Bashir would not budge until it was too late in the day. The fundamental questions have not been asked: what led Sudan under Omar al-Bashir to support international terrorism, to harbor Al Qae’da terrorist organization including Osama bin Laden for many years knowing fully well this will draw the ire of the United States which was already demanding and hunting for the head of Osama bin Laden worldwide as its Public Enemy No 1? Why was Sudan seemingly been supported by certain Middle East countries in its terrorist and criminal enterprise, sending Sudan into the dungeon of hell while they are sunning themselves in Paradise-like developed environments?

One of the factors that led to the overthrow of the former military regime led by Omar al-Bashir, apart from the predilection for hobnobbing with international terrorism, was that it has lost its moral high ground and the basis for its rule on all accounts – as well as previous regimes. Omar al-Bashir had held Sudan by the jugular for nearly three decades. Omar al-Bashir can be singularly held responsible for bringing the Sudanese into a cul-de-sac. The military image was badly tarnished as a result of repressive and authoritarian character of Omar al-Bashir-led military-cum-civilian (hybrid) regime. The National Congress Party which he led became tired of him especially after breaking up with Hassan Abdullah el-Turabi, the Islamic fundamentalist ideologue. Supporters of NCP were abandoning the party in droves. The awe with which the military was hitherto held vanished over time and space. This was what led to huge loud street protests that started in 2018 which led to the climax of the Sudanese state crisis in 2019 that led to throwing out of Omar al-Bashir. Omar al-Bashir himself was thrown into jail without hesitation, pushed into two-year imprisonment after been found guilty of corruption charges; and he is already wanted by the International Criminal Court on the charges of genocide and war crimes in Darfour. Sudan finds itself in a dilemma whether to hand over al-Bashir to the ICC or not.

But reviewing the momentous events of 2019, it can be concluded that the Sovereign Council/Transitional Council was a product of the time. There was no other viable alternative. It could probably not have been otherwise because there seemed to be no substitute at the time as the State was lurching from one crisis to another – ultimately towards State collapse itself. The Transitional Military Council that preceded it was disbanded after it was wholly rejected by the masses of the populace who wanted a clean break from authoritarian or despotic rule under President Omar al-Bashir. The Sovereign Council that replaced the Transitional Military Council reflects the delicate balance of forces or power in Sudan at the time; the deep division within the Sudanese society; and the desperation to hang on to a kind of State structure that can mediate power and prevent the State from complete collapse.

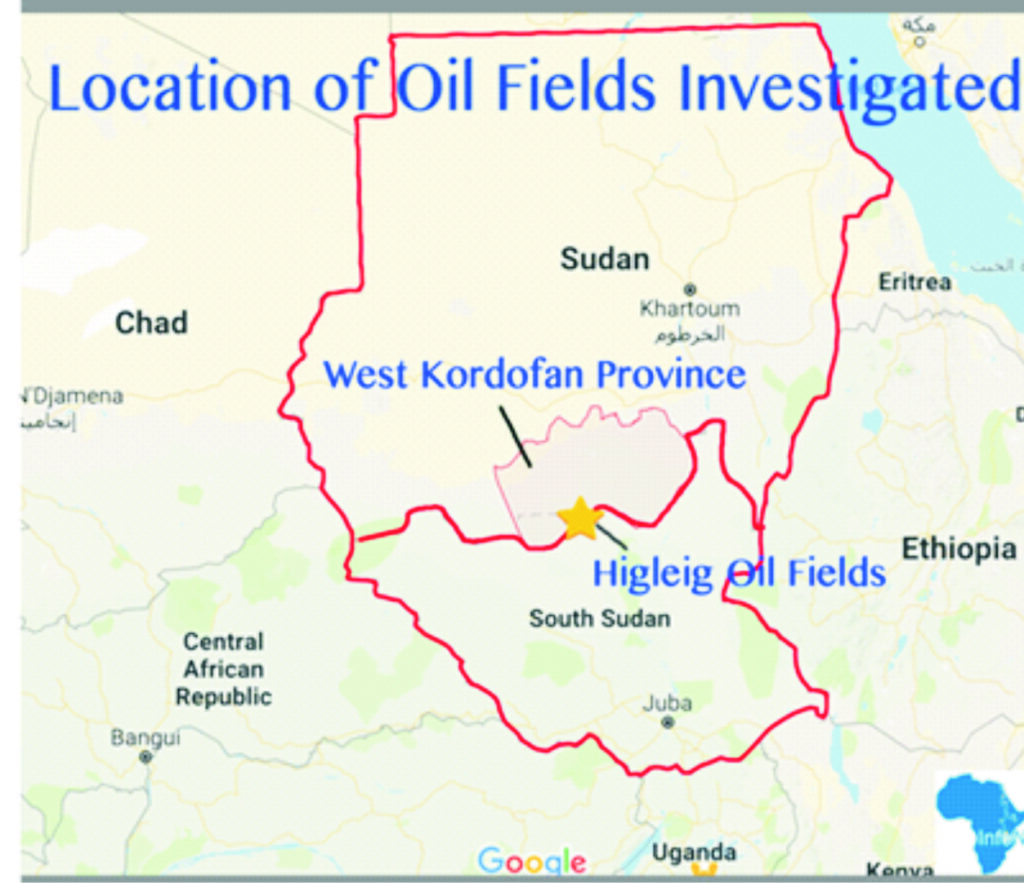

The agreement to divide the government between military and civilians, which followed decades of Bashir’s dictatorship, also offered some hope that it could solve some of the impoverished country’s economic problems, finance its paralyzing external debt and attract foreign investment, especially after it signed a normalization agreement with Israel and former U.S. President Donald Trump removed it from America’s list of state sponsors of terrorism. After the Sovereignty Council was formed [in August 2019], Sudan got several billion dollars from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates as recompense for participating in the war in Yemen, and international oil companies expressed interest in exploring for oil there.1

Yet the ruling clique thrown up by the departure of al-Bashir from power still harbored elements loyal to the disgraced regime.

The October 25 coup, unlike the coup elsewhere (such as in Guinea), was met with hostility from the streets from the very beginning by thousands of people protesting against the coup and vowing not to leave the streets until the transitional government headed by Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok is restored back to power. Again, this was not only a continuation of the struggle of the masses of ordinary Sudanese that saw the end of Omar al-Bashir-led authoritarian regime in 2019, but also the vow to edge out the military completely from the governance space in Sudan. How this protest would restore Abdalla Hamdok back to power is unknown. Has the coup not thrown up new dynamics? Are we still looking at status quo ante or a new constellation of power?

Soldiers have already fired and killed over score protesters. Fourteen people have reported died from the bullets of soldiers as at November 12, 2021. This showed the readiness of the military to hang on to power at all cost including sacrificing the lives of Sudanese on the streets. It is also obvious that the military is finding it increasingly difficult maintaining itself in power because it does not enjoy popular support coupled with pressures from the international community.

Never before has a military takeover been met with such stiff opposition from the very beginning from the majority of the citizens including the international community in defense of the idealistic principles of democratic rule that is still hanging in the air. Democracy has won the hearts and minds of the majority of Sudanese. Al-Burhan and his fellow military Junkers did not bargain nor make contingency plan for such a poor reception or high-tension opposition to their power grab. Their propaganda machine is exceedingly weak and seemingly overwhelmed by that of the opposition. The military junta can only hang on to power by sheer brute force. The military intervention has lost its moral high ground of legitimacy even before gaining it because the intervention was mis-prioritized, and evil in nature exclusively directed at scuttling the transition process to democratic rule in 2023.

The new military junta is evidently not in control of all vectors of State power up to a point in time, at least a week after the coup. The Ministry of Information, ostensibly under the control of the civilians was issuing counter-narratives and even directives against the military – even though certain media houses were invaded by soldiers and ransacked. The Ministry called on Sudanese to oppose the military attempt “to block the democratic transition”. “We raise our voices loudly to reject this coup attempt,” it said in a statement at the heat of the crisis. While one may speak of temporary existence of dual power in the State, events of few days after the coup clearly indicated that the military has gained the upper hand and is perhaps ready to face all odds and obstacles that may come its way both from within Sudan and from the international community. That was why the military junta shut down the internet in order to disrupt communications among the citizens.

There is need for a united front (as witnessed in 2019) galvanizing the populace against the military Junkers. But this united front must have a clear focus and goals that reflect the genuine interests of the Sudanese. While there are, for instance, Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), Sudanese Professional Association (SPA), the Communist Party, the Umma Party, the Sudanese Congress, and various resistance committees including labour unions and civil society organizations, there does not seem to be a central coordinating committee managing and directing the revolutionary energy of the masses of the populace towards a particular goal thus making the protests look more like a barefoot revolutionary movement. There is no clear revolutionary leadership anywhere to be seen – a major deficit on the part of the civilian populace. This has led the military junta to gain the upper hand in this epochal clash between the military and the masses.

However, the civilian leaders seemed to have enjoyed enormous sympathy and support of the populace initially, the latter that has borne the brunt of military repression, brutality and general insecurity of lives and properties including economic crisis over the decades. Yet these civilian leaders have not shown how to mobilize and harness the kinetic energy of the masses and domicile it within a particular framework for liberating Sudan from the vicious grip of the military Junkers. Sudan has been in the grip of insecurity, economic crisis, political instability and nationalist agitations of its own making over the decades escalated by the incompetence and stinking corruption of the military Junkers while the civilian leaders have not been able to point the way forward. Nationalist agitations, for instance, along religious lines have led to the breakaway of South Sudan in May 2011 till date. The people who have died so far may have done so in vain because of the ineffectiveness of the civilian leadership and not just the brutality of the military.

Why this coup at this point in time? Even though the military can be said to still be in charge of the country with the facilities of inflicting violence on the populace under its control, the fact that it hitherto has to share power with the civilians under any pretext is abhorrent to it. It is this abhorrence that has contributed to the hatching of the October Coup. Part of the reasons for the coup include the expected changes in personnel to the Sovereign Council where the headship of the council was expected to pass from General Abdel Fattah al-Burham to a civilian figure including other changes. The reasons also include the looming reform of the military and the security sector (especially the paramilitary bodies such as the Rapid Support Forces and the mortal fear among the military high command with which these impending reforms are being regarded.

However, the Sovereign Council has been embroiled in intense internal debate on many issues which include the direction of the transition process and what it demands, the question of how to handle the case of Omar al-Bashir that is already in prison: whether to hand him over to the International Criminal Court for prosecution on charges of war crimes and other ancillary matters or not. Also in the crucible of debate is the raging economic crisis signposted by skyrocketing inflation, devaluation of currency and imposition (lifting) of fuel subsidies. There was no clarity and clear focus from the office of the Prime Minister and the military adventurists were able to exploit this confusion or lack of direction to their own strategic advantages. Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok was left like a fish out of water fighting for his life.

Africa Confidential gave insights into what might have possibly caused so much rancor and/or virulent disagreements within the Sovereign Council, or between the two main factions within the Sovereign Council, i.e. between the military wing and the civilian wing. The first insight perhaps is the economic reforms embarked upon by Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and the effects of these reforms on the overall economy and how these reforms have impacted on people’s standards of living. The second insight is the plan to restructure and review the accounts of some 600 state companies most of which are in the hands of military men both serving and retired including security sector reform.

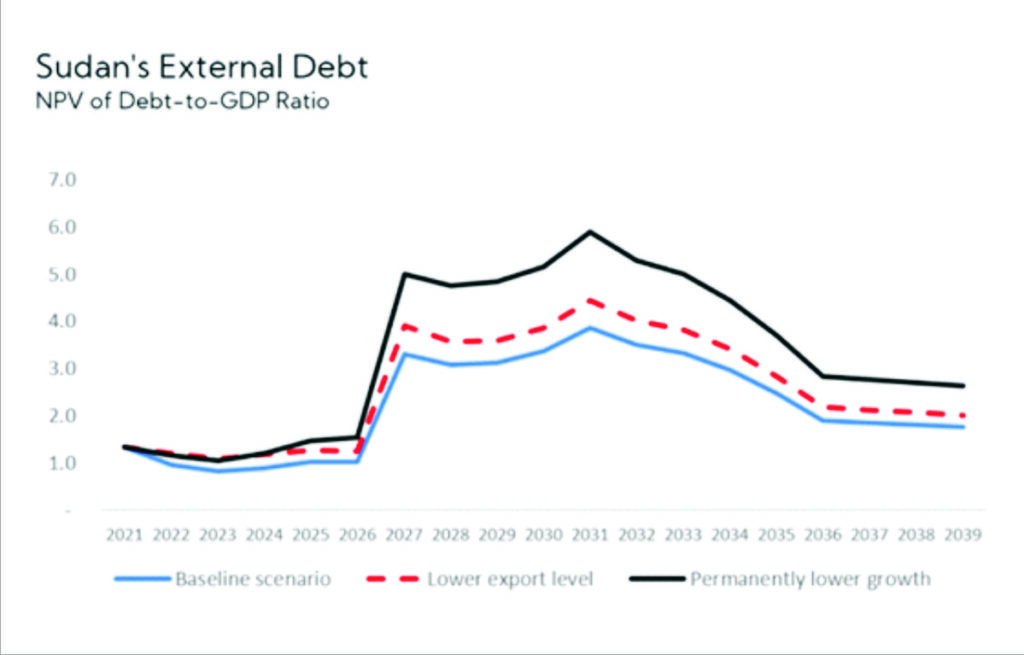

Africa Confidential referenced the Paris Economic Summit that took place in May 2021, a Summit superintended by French President, Emmanuel Macron, and many African countries that trooped to Paris like beggars. “The two days of economic brainstorming on African economies in Paris started well on the morning of 17 May when Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok set out his government’s reform plans which could unblock a plan to restructure much of the country’s $60 billion foreign debt”2

France’s Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire added the pledge of a $1.5bn bridging loan to settle Sudan’s arrears to the International Monetary Fund. Britain, Ireland and Sweden have made similar loans to repay Khartoum’s arrears to the African Development Bank, and the United States has provided a bridging loan to pay off arrears to the World Bank.3 That means Sudan could start its debt-relief programme, under the IMF and Bank’s Heavily Indebted Poor Country Initiative, late next month [June/July 2021]. It would allow the country to borrow another $2bn from the Bank to fund urgent development projects, and bring in the IMF to finance more economic restructuring.4

Those initial economic changes – ending fuel subsidies, raising the power tariffs and liberalising forex policy – have all pushed up prices and are politically risky. The introduction of the government’s Family Support Programme, designed to compensate most Sudanese, is helping.5

But the next stage of economic reforms, which includes restructuring and reviewing the accounts of some 600 state companies, may be riskier still.6 Many of these companies, which have corruptly benefited from public funds, are in the hands of Islamist acolytes of the former ruling party or the military and intelligence services.7

Under new Finance Minister Jibril Ibrahim, many of these companies are meant to be under treasury surveillance but local anti-corruption activists say that political ideologues and security officials are pushing back hard. This year about 22% of the national budget is allocated to the military whose management is opaque.8 But individual officers also get access to funds directly from the ‘military-industrial’ companies such as Giad, which comes under the ministry of defence, as part of a complex network of companies and subsidiaries.9

A new report by Sudanese researcher Suliman Baldo, now of the US-based Sentry Group, highlights the role of Al Sabika Al Zahabia, a gold mining company which it says is still controlled by the General Intelligence Service.10 It adds that Lieutenant-General Abdul Rahim Hamdan Dagalo, the second-in-command of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the rebadged Janjaweed militia operating in Darfur, and Deputy Chair of the ruling Sovereign Council has incorporated several private companies in Sudan and the United Arab Emirates. These companies are reported to be carrying out contracts for the RSF under opaque arrangements.11 Depriving the Hamdok government of this revenue adds to the political risks it faces. Should it fail to convince young Sudanese that it is able to resuscitate the economy it could face the same sort of popular protests that led to the toppling of the Islamist National Congress Party regime in April 2019.12

It is very clear that the Sovereign Council inherited a financially bankrupt State by the time it took over in August 2019. Sudan was barely coasting along. Sudan can be seen to be lying on a financial stretcher being taken for emergency treatment in the IMF/World Bank “hospital” where there is 50/50 survival chance. Had France, including other European powers, not pledged to bail out Sudan with soft loans to repay IMF loan, Sudan would have buckled under the weight of its suffocating external debt. It is these countries that donated water, oxygen and blood to save Sudan, give a chance for survival. The vultures would have landed to tear apart Sudan financially.

The working relationship between the members of the Sovereignty Council was tenuous, reflecting their sometimes competing interests as well as general ideological divisions in the country. In addition to the primary civilian-military divide, there were also internecine squabbles on both sides. Furthermore, the country’s economy was in crisis, which also fomented discontent among the general population. There were multiple instances of coup plotting or attempted coups during the transition period, including one attempt on September 21, 2021, launched by Bashir loyalists. The military subdued the coup action but also laid blame for the attempt at the feet of the civilian leaders, whom they deemed ineffective, and called for them to be replaced. Civilian leaders accused the military of using the attempted coup as an excuse to try to secure more positions of power in the transitional government. They also reiterated the need to restructure the military, review its business interests, and bring them under civilian oversight—propositions not popular with many in the military. Thus, the level of tension between the military and civilian leaders, which had already been simmering at dangerous levels, further increased in the aftermath of the coup attempt. Several protests were held in October, with some demonstrators calling for the military to oust the civilian leaders while still more called for the military to respect civilian rule and the democratic transition.13

On October 25 the military launched a coup with the backing of Burhan and other top military officials. Hamdok and other cabinet ministers were arrested. Burhan dissolved the Sovereignty Council, declared a state of emergency, and pledged to hold new elections in July 2023. In Khartoum, Omdurman, and other locations across the country, protesters rallied against the coup, and several civil and professional organizations called for strikes and acts of civil disobedience. The next day Burhan claimed the military took the actions that it did in order to avoid a civil war; those supporting a return to civilian rule were not mollified by his words, and protests continued. Meanwhile, the military coup was widely condemned on the international stage and jeopardized plans for much-needed aid and debt relief for the country. The AU suspended the country once again.14

It is evident that the Sovereign Council was sharply divided mostly between the military men and the civilians. Whoever move first and fast enough will definitely gain the upper hand in the struggle for hegemony or domination within the Council. General al-Burhan was the first to move and fast enough to brush or shove aside the civilian members of the Council. He moved like a lightning speed to prevent himself from been removed or dropped as the head of the Sovereign Council. It was a desperate instinctive act of self-preservation from a looming political annihilation. The September 21 attempted coup was a rehearsal. Interestingly nobody knows what has happened to those who allegedly carried out the coup till date. But it is noteworthy that in carrying out the coup, al-Burhan hardly mentioned anything about the state of the economy.

Burhan argued it was incumbent on the armed forces to act after infighting between some political forces and “the striving for power” and “incitement to chaos and violence” in which he himself is involved and is now the main beneficiary. In the televised address, Burhan said infighting between politicians, ambition and incitement to violence had forced him to act to protect the safety of the nation and to “rectify the revolution’s course”. He said Sudan was still committed to “international accords” and the transition to civilian rule, with elections planned for July 2023. Al-Burhan did not per chance mention the raging economic crisis. None of the corpus of his stated arguments can be argued to amount to doctrine of necessity as the basis of the coup. While the Sovereign Council was in crisis of disagreements within itself, there is no evidence to show that the Sudanese State has completely lost focus and is drifting into total chaos. General al-Burhan concocted those arguments as political reasons to help create the crisis to grab power for himself and his coterie of supporters within the military and their external backers.

There is no doubt that the key players especially the civilian leaders in the government are most probably aware that a coup was on its way and that it will happen inevitably one way or the other. But they were seemingly impotent to do anything to avert it. The storm has been gathering momentum since the failed coup attempt on September 21 if not before that time. The storm became a typhoon on October 25 with all the visible ripple effects across the social and national boundaries. It can also be speculated very strongly that General al-Burhan has not only positioned himself as the new grandmaster of Sudanese politics, he was most probably the brain behind the failed coup attempt on September 21 – using his remote control to manipulate events in his favour. The Western intelligence agencies may have only become aware of this fact only too late in the day.

The intervention of the United States through its Ambassador, Jeffrey Feltham, did and could not persuade General al-Burhan from his Manichean quest to become the new sole leader in Sudan. How al-Burhan played this epistemological subterfuge (neuroweaponry) on the Envoy may not be known for a long time to come. Al-Burhan did not believe in the democratic rule scheduled for installation in 2023 despite his lip-service to it. General al-Burhan orchestrated the coup in his interest of self-preservation and not in the interest of the so-called security and stability (the usual excuses). His career is already on the line including the prospects of being called upon to account for his stewardship as one of the key actors behind-the-scene during Omar al-Bashir reign and the arrowhead of the June 2019 Massacre and the shady deals involved with the military-industrial complex.

The above provides the backdrop or contextual problematique that formed the canvass or general context of the coup.

The General Context

Sudan has been unable to find a workable political system since independence in 1956 and has seen numerous coups and coup attempts or general sociopolitical instability. The Transitional Military Council that came into being in April 2019 after the overthrow of President Omar al-Bashir later transmuted into a Sovereign Council, the latter which has been struggling to stabilize the country, end the pariah stigma of Sudan, improve the economy that has largely bellied-up and sustain the transition amid bitter factional dogfights between the military and civilian elements within the Sovereign Council, the larger Sudanese intelligentsia and society. The Sovereign Council succeeded in securing a reprieve from the United States when the latter finally bent backward and removed Sudan from the list of global State Sponsors of Terrorism in December 2020 by former President Donald Trump.

Sudan faced epochal crisis which was largely self-inflicted over the arch of time and space. Sudan has been ruled for most of its post-colonial history by military leaders who seized power in coups. It had become a pariah to the West and was on the U.S. terrorism blacklist under Bashir, who hosted Osama bin Laden in the 1990s and is wanted by the International Criminal Court in The Hague for war crimes.15

To fast-forward, [t]he country had been on edge since last month [September] when a failed coup plot, blamed on Bashir supporters, unleashed recriminations between the military and civilians in the transitional cabinet.16 In weeks [prior to the coup] a coalition of rebel groups and political parties aligned themselves with the military and called on it to dissolve the civilian government, while cabinet ministers took part in protests against the prospect of military rule.17 Sudan has also been suffering a grave economic crisis. Helped by foreign aid, civilian officials have claimed credit for some tentative signs of stabilisation after a sharp devaluation of the currency and the lifting of fuel subsidies.18

Washington had tried to avert the collapse of the power-sharing agreement by sending [its] special envoy, Jeffrey Feltman. [When the coup finally happened] [t]he director of Hamdok’s office, Adam Hereika, told Reuters the military had mounted the takeover despite “positive movements” towards an agreement after meetings with Feltman in recent days.19 White House spokesperson Karine Jean-Pierre said: “We reject the actions by the military and call for the immediate release of the prime minister and others who have been placed under house arrest.” Democratic Senator Chris Coons, chairman of the Senate subcommittee that oversees foreign aid, said on Twitter U.S. support for Sudan would “end if the authority of PM Hamdok & the full transitional government is not restored”. A U.S. law bars funding governments brought to power by a military coup.20

The United Nations, Arab League and African Union all expressed concern. Sudan’s political leaders should be released and human rights respected, AU Commission Chair Moussa Faki Mahamat said in a statement. Britain called the coup an unacceptable betrayal of the Sudanese people. France called for the immediate release of Hamdok and other civilian leaders. Egypt called on all parties to exercise self-restraint. Saudi Arabia said it was following developments with extreme concern.21

The Sudanese Professionals Association, an activist coalition in the uprising against Bashir, called for a strike. Burhan’s “reckless decisions will increase the ferocity of the street’s resistance and unity after all illusions of partnership are removed,” it said on its Facebook page. The main opposition Forces of Freedom and Change alliance called for civil disobedience and protests across the country.22

Military forces stormed Sudanese Radio and Television headquarters in Omdurman and arrested employees, the information ministry said on its Facebook page. Two major political parties, the Umma and the Sudanese Congress, condemned what they called a coup and campaign of arrests.23 Internet access was widely disrupted and the country’s state news channel played patriotic traditional music. At one point, military forces stormed the offices of Sudan’s state-run television in Omdurman and detained a number of workers, the Information Ministry said.24

Since al-Bashir was forced from power [in April 2019], Sudan has worked to slowly rid itself of the international pariah status it held under the autocrat. The country was removed from the United States’ state supporter of terror list in [December] 2020, opening the door for badly needed foreign loans and investment. But the country’s economy has struggled with the shock of a number economic reforms called for by international lending institutions.25

Multiple videos posted to social media on Monday [on the day of the coup] showed hundreds of demonstrators walking towards army headquarters, chanting: “We are walking holding worry in our hearts — and worry sleeps in people’s chests.” Some videos showed protestors removing razor wire that had been placed across a road amid reports of street closures in several parts of the city.26

Bullets were fired at protesters demonstrating against the coup outside Sudan’s General Command in the city, the Ministry of Information said in another statement. The Ministry said there were casualties, but did not clarify how many shots were fired, or who was shooting at demonstrators. The Central Committee of Sudan Doctors, who are aligned with the civil component of the now-dissolved Sovereign Council, said that two people were killed and more than 80 were injured in the incident.27

One eyewitness told CNN demonstrators had blocked three main bridges in Khartoum, including one that connects Omdurman to the capital and leads to the presidential palace. Security forces briefly fired tear gas near that bridge to disperse protesters, the eyewitness said, explaining that the security forces patrolling the streets are mainly military and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. There was minimal police presence on the streets, the eyewitness added. As chaotic scenes played out across the capital, flights from Khartoum International Airport were canceled, and mobile phone networks and internet access were disrupted.28

According to Anne Soy, [r]ecent weeks have seen a rapid build-up of tension in Khartoum. A hostile takeover of power is what many in Sudan and beyond have feared could happen anytime. The signs have been all too clear. A pro-military sit-in right in front of the presidential palace in Khartoum was seen as choreographed to lead to a coup. No attempt was made to disguise its purpose. The protesters demanded that the military overthrow “failed” civilian leaders. It was an unusual attempt at legitimising a military takeover, using the guise of a popular protest. Nearly a week later, a counter-protest was held. This time, huge crowds came out in support of the civilian government.29

According to Joseph Tucker, “[d]isagreements over power wielded by civilian and military components of Sudan’s government led to this moment. On the surface, the planned leadership transfer of Sudan’s ruling Sovereign Council – the mixed military and civilian body led by Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan – to civilian control likely increased resistance within the military to cede power, as did calls for accountability and comprehensive security sector reform. However, the splintering of civilian political coalitions, increasing overtures to the military from signatories to the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement (JPA) and tensions within the security sector all contributed to a volatile political situation ripe for such an action. The military appears to have seen a need to protect its interests, and more importantly, an opportunity to do so.”30

The relationship between the military, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) under Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti) and the Sudanese public provides the sobering backdrop for the coup. The armed forces have often played an outsized role in Sudanese politics, and the litany of attempted and successful coups attests to this. The military often projects itself as the defender of the nation, and it appears to be reinforcing this narrative after the takeover.31

Citizens’ frustration with political deadlock, impatience with the pace of economic recovery and perceived regional support may have led the military to think its action would at least be tolerated. During a press conference on October 26, al-Burhan bluntly noted that the military took action to get the transition back on track and avoid conflict. He expressed frustration that the military had been excluded from key discussions and unfairly targeted. These suggestions were met with derision and anger among many Sudanese, including those protesting on the streets and among the diaspora. While the military tries to recruit members of what will probably be a controversial new government, a central theme will remain: What role should the military have going forward and how can this be shaped given the coup?32

But the ease with which the coup was carried out showed the fragility of the Sudanese State especially its lack of conflict or coup-prevention institutional mechanisms. The structure of the Sovereign Council, the highest ruling body, makes it easy for the coup to take place. It is evident that General al-Burhan calls all the shots within and from without the Council. But that is precisely the fundamental character flaw of the Council which has a careered military officer as the supreme head and a deputy in the person of Major General Hamdan Dagalo, the head of the Rapid Support Forces and a man with questionable track record, who can easily kick the Prime Minister in the ass or groin and boot him out of the Presidential Palace – precisely what has happened.

The situation is similar to what happened in Mali earlier in the year when “the Malian military also struck in its own fashion leading to the arrest, detention and forced resignation of the government led by President Bah N’Daw and Prime Minister Moctar Ouane, including the Defence Minister, Souleymane Doucoure on May 24, 2021.”33 Colonel Assimi Goita, who was the Vice President, accused the President of carrying out a cabinet reshuffle that removed his own supporters from the loop of power. But it was also an act of self-preservation, knowing unmistakably fully well that the President was also coming for him inevitably.

On Sunday September 5, 2021, the elite Special Forces soldiers of the Guinean Army announced that they have toppled the “democratic” government headed by 83-year old President Alpha Conde. Thus, another setback to democratic rule was recorded on the African continent shortly after Chad and Mali followed the same route of coup d’état this year.34 In announcing the take-over, the new head of the military junta, Lt. Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, a former French foreign legionnaire, said on national television that “We have dissolved government and institutions.” “We are going to rewrite a constitution together.”35

Within the week of the military takeover in Sudan, the new military strongman, General al-Burhan, was already calling the shots across the national boundary by relieving six Sudanese ambassadors from their posts, including in Washington and Paris, state TV reported on Wednesday [October 27] –thus showing the whole world who is now in charge of Sudanese State. The decision included Sudan’s ambassadors to the US, EU, France, China, Qatar and the head of Sudan’s mission to Geneva. The West has called for Hamdok’s government to be reinstated immediately, stressing that they only recognize the prime minister and his cabinet as the constitutional leaders of Sudan. The African Union suspended Sudan on Wednesday [October 27] until civilian rule is restored, rejecting the military takeover as an “unconstitutional” seizure of power.36

Also as part of the fallouts from the coup (a week after the coup) a number of high-ranking members of Omar al Bashir’s now-dissolved National Congress party (NCP), including its former leader, Ibrahim Gandour, were released by military authorities as demonstrators continued to take to the streets to protest the military coup. Gandour was arrested in June 2020 for allegedly planning sabotage operations against the government of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. Sudan state TV reported that Anas Omer, the former East Darfur governor, and former intelligence service communications head Mohamed Hamid Tabidi were also released. Mohamed Ali Al-Jazoli, the leader of the State of Law and Justice party (SLJP), a jihadist group, was also allowed to leave prison.37

After the releases were announced, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan dismissed acting attorney-general Mubarak Osman but gave no reason why. Osman had been working on investigations on the Islamists who were released.38

Demonstrations rocked Omdurman and Khartoum on Sunday [after the coup]. Khartoum has largely been shut down as protesters set up roadblocks. Civil servants are refusing to work and shopkeepers have shuttered businesses. The Sudan Doctors Committee said that the overall toll was 12 dead since the coup started on 25 October. At least three people were shot dead and 100 wounded on Saturday (October 30, 2021) during the protests. The police denied using live rounds but doctors report that dead protesters have bullet wounds in the head, chest and stomach. The paramilitary Rapid Support Forces remained on the streets of Khartoum and twin city Omdurman on Monday. The group gained notoriety under al-Bashir for its operations in Darfur. It was also part of the bloody crackdown on a sit-in outside the military headquarters in Khartoum in June 2019.39

A Much-anticipated Coup

According to Africa Confidential, prior to the Coup, a shadowy alliance with links to the ousted Beshir regime is calling for a coup against the transitional government.40 Efforts to derail Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok’s reform agenda and oust the civilian-dominated council of ministers have intensified with a military-backed protest in Khartoum on 16 October. This follows an attempted putsch, seen by many as a rehearsal, on 21 September and weeks of orchestrated disruption at Port Sudan ratcheting up the country’s economic woes.41 The pro-military demonstrators called on General Abdel Fattah Burhan, commander of the armed forces and current head of the joint civil-military Sovereignty Council, to mount a coup against the civilians in the power-sharing government.42

Their timing is critical. This year, Gen Burhan is due to step down as the military’s chair of the Sovereignty Council to be replaced by a civilian appointee. And the council of ministers is organising an international conference next month to raise funds for its economic reform programme.43 Civilian activists suspect collusion between the organisers of the Khartoum protests, and the security forces. Many of the demonstrators were bussed in from outside the city.44 Khartoum’s State Governor Ayman Khalid accused an armed group, apparently with links to the military command, of removing guard rails around key government buildings. Police and other security officers meant to protect civilians in the government were withdrawn on the day of the pro-military protests.45

This transfer of power was supposed to have taken place next month [November 2021], thereby completing a temporary arrangement that was supposed to lay the groundwork for democracy in the country. But when Gen. Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, the Sovereignty Council’s vice chairman, asserted that “we’ll never transfer intelligence and the police to civilian management,” it became clear that an orderly transfer of the council’s leadership wasn’t part of the military’s game plan.46

Dagalo’s remarks also revealed a deep disagreement within the army’s ranks between those considered loyal to Bashir – including Dagalo himself – and those loyal to al-Burhan, who decided on Monday to dissolve the government and declare a state of emergency. Al-Burhan was primarily afraid of Dagalo’s forces, which are thought to total around 30,000 soldiers, but also of the independent militias, which waged violent battles until an agreement was reached in October 2020 on a cease-fire and division of the spoils.47 That agreement, which was signed in and named after Juba, the capital of South Sudan, was supposed to calm the militias and the tribes that opposed the new government. But it also included the seeds of the civil unrest that broke out last month.48

Six days before the coup, Middle East Eye also published an article which raised fear about a likely coup.49 But it is very doubtful whether Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and his supporters ever paid sufficient attention to this likelihood even with the failed coup of September 21 which served as a serious warning or harbinger of what is to come later.

Pro-democracy protesters, analysts and politicians in Sudan are worried the recent rise in tensions between military and civilian factions of the transitional government could lead to a power grab by the army, warning of a scenario similar to the 2013 coup in Egypt some three years since the ousting of autocrat Omar al-Bashir.50

The Sudanese army, backed by paramilitary groups, is strongly pushing for dissolution of the civilian wing of the government headed by Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, marking the biggest political crisis in the country’s transition to civilian rule.51

The situation has heated up since [the previous] Saturday, when thousands of military supporters began a sit-in near the presidential palace, sparking sporadic confrontations between the backers of the army and the civilian authorities amid acute shortages of bread and fuel in the entire country.52 Plans for a pro-civilian march on Thursday also raise the possibility of further escalation in coming days, while sources told Middle East Eye that negotiations have already begun to dissolve – or, at least, significantly reshuffle – the current cabinet.53

Since August 2019 – four months after Bashir was ousted by a mass protest movement against his nearly 30 years of rule – Sudan has been led by the Transitional Sovereign Council, made up of five civilians chosen by the leading organisations of the anti-Bashir movement, five military representatives, and a chairperson alternating between the two factions.54

However, the two branches of government have been at odds from the beginning, and a failed coup in September – blamed on Bashir supporters backed by armed forces – has heightened fears that the military is seeking to undo efforts to bring democracy to Sudan. The head of the army and current chairman of the Sovereign Council, Abdul Fattah al-Burhan, called for the dissolution of the civilian government led by Hamdok, arguing that the move would resolve the current political deadlock in the country.55

Apprehension has only intensified since Saturday, when thousands of former armed militants and supporters of the army first staged a sit-in around the presidential palace in the capital, calling for the immediate dissolution of the civilian cabinet. The streets of downtown Khartoum near the palace and not far from the Council of Ministers were filled with thousands of former members of the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM/A) rebel group, whose leader Minni Arko Minnawi is also the current governor of Darfur, and of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) headed by Finance Minister Jibril Ibrahim.56

While the SLM and JEM once fought against Bashir at the height of the VBNM conflict in Darfur in the 2000s, the rebels now hold the civilian factions responsible for delays in implementing the Juba peace agreement, signed in 2020 between the transitional government and the country’s many warring factions. “We won’t leave this square until this government is dissolved,” former Darfuri rebel Ahmed Al-Mukhtar told MEE. “Those civilians have hijacked the revolution and this is the attitude of a dictatorship in itself. They are saying they are against any potential military coup, but let me tell you that the civilians have committed a coup against the revolution and we are here to address that.”57

On the other side of the aisle, the current political civilian coalition – composed of the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), the Sudanese Professional Association (SPA), resistance committees, unions and other civil society organisations – has called for a “million-man march” on 21 October against the military. “We will fill these streets to show them our power and our representation of this revolution,” a statement by neighbourhood resistance committees in Khartoum read. “We are willing to die like our brothers who were killed by the same forces that now want to return to power. “We will show those remnants of the old regime, including the army, how the fight for freedom is rooted amongst our people,” the statement added.58

Amid the ongoing power struggle in Khartoum, the army scored another advance as pro-military protesters in eastern Sudan, headed by tribal leader Mohamed al-Amin Tirik, shut down ports and blockaded roads leading to the rest of the country, affecting the supply and distribution of food, bread, fuel and other materials. Deputy chairman of the Beja Congress political group, Shaiba Dirar, said that the port and road closures would continue until the demands of the ethnic Beja group were addressed, notably the cancellation of the sections of the Juba peace agreement pertaining to eastern Sudan. “Our demands mainly are against the eastern Sudan track in the Juba peace agreement, because it’s unfair and doesn’t represent the real and genuine leaders of eastern Sudan,” Dirar told MEE, arguing that the agreement affected “the security, politics and economy of the entire region”.59

Supporters of Hamdok’s cabinet have accused Beja leaders of being manipulated by the army, an allegation that has caused anger among the Bejas. “Eastern Sudan has very fair demands of equality and a stoppage of the historical marginalisation of our region and people,” Dirar stressed. “We are very frustrated with the civilians who are leading the country now, this is why we believe that the military component in the transitional government has a great role to play now to protect the country and defend its sovereignty and its national unity.”60

Western diplomats and sources close to Hamdok have meanwhile disclosed that talks have begun between the two sides to broker a solution to the current crisis. The sources, who requested anonymity because they were not authorised to talk to the media, revealed that the talks were seeking to negotiate a new power-sharing agreement. “It may not be a direct dissolution of the government or major changes to the constitutional declaration signed in August 2019, but a kind of wide reshuffle that can grant a larger percentage of the power-sharing quota to the rebels and pro-military supporters,” the sources said.61

A Sudanese scholar at an international think tank told MEE they believed Sudan could witness a setback in its transition through a “soft coup” that would allow some former associates of Bashir to take part in the transitional government. “It may not be a traditional military coup like the Egyptian and Tunisian scenario, but it has a lot of similarities, and in the end it will change the balance of power in favour of the old regime and the military,” the expert, who asked not to be named, predicted. The academic said many factors were at play in the current power struggle in Sudan – including army generals’ concerns over calls for accountability in the mass killing of protesters on 3 June 2019, as well as their economic and political ties to the former Bashir administration.62

Meanwhile, the 2019 constitutional declaration that had paved the way for Burhan to head the Sovereign Council for 21 months meant the general should have handed over the seat to a civilian representative back in May – a transition that has yet to take place. “We are somehow facing a scenario similar to Bashir’s last years in power, when he wanted to secure a safe exit from being tried by the ICC, so dealing with the military needs some flexibility in terms of opening a narrow door for a way out with some guarantees,” the academic concluded.63

Atlantic Council fellow and former US diplomat Cameron Hudson also believes that Sudanese forces are securing means for themselves to evade accountability. “Is any compromise possible here? The security services must have an exit strategy, they are cornered and fearful of what will happen to them if civilian protesters ultimately get their way,” he told MEE. “We also know that these leaders are not going to walk willingly into the arms of the ICC or into Kobar prison. They must feel that if they relinquish power they will survive in a future Sudan; this will require trade-offs that could be unpopular.”64

In recent weeks, there have been concerns that the military might be planning a takeover, and in fact there was a failed coup attempt in September. Tensions only rose from there, as the country fractured along old lines, with more conservative Islamists who want a military government pitted against those who toppled al-Bashir in protests. In recent days, both camps have taken to the street in demonstrations.65

Amid the standoff, the generals have called repeatedly for dissolving Hamdok’s transitional government – and Burhan, who leads the ruling Sovereign Council, said frequently that the military would only hand over power to an elected government, an indication that the generals might not stick to the plan to hand leadership of the body to a civilian sometime in November. The council is the ultimate decision maker, though the Hamdok’s government is tasked with running Sudan’s day-to-day affairs.66

As part of efforts to resolve the crisis, Jeffrey Feltman, the U.S. special envoy to the Horn of Africa, met with Sudanese officials over the weekend, and a senior Sudanese military official said he tried unsuccessfully during his visit to get the generals to stick to the agreed plan. The arrests began a few hours later, said the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to brief media.67

In recent weeks, the military has been emboldened in its dispute with civilian leaders by the support of tribal protesters, who blocked the country’s main Red Sea port for weeks. The most two senior military officials, Burhan and his deputy Gen. Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, also have close ties with Egypt and the wealthy Gulf nations of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.68

The first reports of a possible military takeover emerged before dawn, and the Information Ministry later confirmed them hours later, saying Hamdok and several senior government figures had been arrested and their whereabouts were unknown. Internet access was widely disrupted and the country’s state news channel played patriotic traditional music. Hamdok’s office denounced the detentions on Facebook as a “complete coup.” It said his wife was also arrested.69

Sudan has suffered other coups since it gained its independence from Britain and Egypt in 1956. Al-Bashir came to power in 1989 in one such takeover, which removed the country’s last elected government.70

Among those detained Monday were senior government figures and political leaders, including the information and industry ministers, a media adviser to Hamdok and the governor of the state that includes the capital, according to the senior military official and another official. Both spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to share the information with the media.71

After news of the arrests spread, the country’s main pro-democracy group and two political parties issued appeals to the Sudanese to take to the streets. The Communist Party called on workers to protest what it described as a “full military coup” orchestrated by Burhan.72

What became apparent was that Sudan has run into a political gridlock even when the Sovereign Council was still in charge. But what caused this gridlock might not unconnected with crisis of governance or administration, again with active involvement of the Sovereign Council in this crisis. Sudan is sharply divided into a binary opposite: those who want military rule and those who want civilian democratic rule. It is apparent that the military would not take orders from the civilian leaders and this inevitably led to breakdown of authority with the consequence of “everybody taking law into their hands” thus returning the State into a kind of Hobbesian state of nature where every man is for himself God for everybody!

It was equally evident that Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok is not in any way in control of any vector of State power. He saw the handwritings on the wall but could do nothing to prevent the handwritings from coming into materialization. He could not single-handedly sack General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan but preferring to wait till he was legally replaced by a civilian in accordance with the internal agreement about rotation of the chairmanship of the Sovereign Council between the military and the civilians. Al-Burhan moved first and kicked Hamdok in the ass out of the Presidential Palace. Hamdok could only engage in knee-jerk protests.

What can also be deduced from the events before the coup was that the coup was already afoot despite the pretension to the contrary. There have been maneuvering and counter-maneuvering among the governing elites jockeying for vantage positions or battling for supremacy. The pro-military demonstrators were the first to come out to the streets calling for a coup and/or the dissolution of the Sovereign Council. This could not have taken place without the knowledge of the military high command. It in fact can be accused to have encouraged it to prepare the ground for its eventual strike. The pro-civilian demonstrators were evidently caught napping because they had no premonition of what was looming on the horizon until the pro-military demonstrators came out to the streets. The pro-civilian demonstrators were caught off-side on the “football field”. In short, the military putschists carefully planned the coup, orchestrated it by using the pro-military demonstrators as auxiliary forces and alibi to mount their coup. It is the Western intelligence community that failed to see the coup coming at the time it did.

Justifying the Military Coup with Specious Arguments

General al-Burhan defended the military takeover of government at the same time double-speaking that the takeover was not a coup but that the Army was [only] trying to rectify the path of the political transition. Burhan says Army ousted the transitional council to avoid civil war but did not show the evidence of this looming civil war.

In an address to the nation on October 25, coup leader Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan justified his actions and reiterated his commitment to “the constitutional path” and the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement with various rebel groups. On the latter front, he called on the last two rebel holdouts – Abdel Wahid al-Nur of the Darfur-based Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) and Abdelaziz al-Hilu of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), based in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan – to fully join the peace process and help usher in “a new Sudan…of freedom, peace and justice.” Burhan, who was previously the country’s de facto head of state before spearheading the coup, sought to portray the military’s action as a “correction” to the transitional process, emphasizing that the revolution was in danger and pledging to appoint a technocratic government that will guide the country to democratic elections in July 2023. Yet the essential question to be decided on the streets of Sudan in the coming days is clear: will the military solidify its rule enough to make and unmake governments for the long term, or will its power decrease in accordance with the framework guiding the post-Bashir democratic transition?73

While speaking at the first news conference after the announced takeover, General al-Burhan accused politicians of incitement against the armed forces as if the armed forces are a sacred cow that cannot be blamed. “Burhan is trying to craft a narrative that posits the military as the savior of an ineffectual and divided civilian government. On Monday he claimed that he only wants the military to hold power until democratic elections can be held in July 2023. This is a lie. The goal here is for the military to retain power in perpetuity”.74

While devastating, there is nothing surprising in Monday’s developments. Opponents of democracy in Sudan’s military and security services have been trying to thwart Sudan’s transition since it began. There have already been several attempted coups, with the latest foiled by Hamdok’s government just last month [September 21]75 “The whole country was deadlocked due to political rivalries,” Gen. Burhan said on Tuesday. “The experience during the past two years has proven that the participation of political forces in the transitional period is flawed and stirs up strife.”76

However, shortly after Gen. Burhan spoke, Mr. Hamdok’s office issued a statement, voicing concerns about the safety of the premier and other detained officials. It did not say where the politician was being held. The statement accused the military leaders of acting in concert with Islamists, who have argued for a military government, and other politicians linked to al-Bashir’s National Congress Party, which was dissolved in 2019. Mariam al-Mahdi, the Foreign Minister in the government that the military dissolved, was defiant on Tuesday, declaring that she and other members of Mr. Hamdok’s administration remained the legitimate authority in Sudan. “We are still in our positions. We reject such coup and such unconstitutional measures,” she said. “We will continue our peaceful disobedience and resistance.”77

Western governments and the UN have condemned the coup and called for the release of Mr. Hamdok and other senior officials. U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration announced the suspension of $700 million in emergency assistance to Sudan.78

Middle East Eye has noted five strange contradictions in Burhan’s speech at the first press conference which “have raised eyebrows amongst those who have been watching events unfold in Sudan”.79

- ‘This is not a coup,’ says coup leader: Burhan, the leader of the army who on Monday dissolved the government and the Sovereign Council in charge of the country’s transition to democracy since 2019, denied in his speech that the operation carried out by the military constituted a coup. Instead, he chose to describe the move as an attempt to “rectify the path” to democratic transition by taking matters into the armed forces’ own hands. Civilian leadership in Sudan – as well as swathes of the international community – have strongly denounced the move as a coup. Army forces raided television and radio headquarters and shut down the internet in Sudan, a textbook approach for a putsch – while Burhan vowed that the internet would be restored “in phases”.80

- Premier not kidnapped, but ‘at my home’: Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and five ministers and civilian members of the country’s ruling council were disappeared in the early hours of Monday. But according to Burhan, there is nothing concerning about that. “Yes, we arrested ministers and politicians, but not all,” he said in the news conference in Khartoum, claiming that all detained officials would have access to due process. Burhan went on to say that Hamdok was “at my home” and “in good health”, adding that the arrest of a sitting prime minister in the middle of the night was “for his own good”. It remained unclear whether Hamdok was indeed being held in the general’s home. Although the premier’s statement from detention on Monday, calling the moves by the military a “complete coup d’état”, cast doubts that Burhan was hosting the politician over for tea. The international community has, meanwhile, called for Hamdok’s immediate release.89

- An army takeover against ‘racism’: Burhan insisted that the coup had to be done to avoid a civil war ignited by a “racist and sectarian” political class, arguing that the seizure of state powers was meant to fulfil the people’s demands and revive the 2019 revolution that toppled longtime ruler Omar al-Bashir. Burhan stressed that telephone and internet networks were shut across the country due to worries about “misinformation and racist behaviour online”. While the military has sought in recent weeks to ratchet up animosity against the civilian leadership among rebel groups across the country, thousands of protesters have taken to the streets since Monday to denounce the coup, chanting one of the slogans of the 2019 uprising: “Freedom, peace and justice.” Patchy internet access has also meant that footage of violent repression against demonstrators – which is reported to have killed several people – has come out of the country in fits and starts.90

- It’s not political: Despite dissolving the country’s political bodies, Burhan said that the decision to seize power was “a national duty, not an agenda”. He vouched that by Wednesday, a new, technocratic governmental structure would be in place to replace the Sovereign Council and that the military would lead the country until elections set for July 2023 – a year later than initially scheduled. However, recent history casts doubts on Burhan’s willingness to follow a timeline. Under a 2019 power-sharing agreement with the civilian leadership, Burhan was supposed to serve as head of state for 21 months before handing over the seat to a civilian representative. The military leader was due to pass the baton in May, but instead held on to the position.91

- Coup seeks atypical politicians: Eager to prove his magnanimity, Burhan said he was open to civilian rule – as long as those leaders wanted to collaborate with the military and were not “typical” politicians. He vowed that the new legislature would include young people from the revolution and would respect democratic principles. “The armed forces will continue completing the democratic transition until the handover of the country’s leadership to a civilian, elected government,” Burhan said. It remains to be seen whether members of Sudan’s popular pro-democracy movement will decide to join forces with the military. But for now, it certainly does not look like any are buying it.92, 93

It is interesting to note that al-Burhan did not state specifically what are his goals apart from the specious arguments mounted as raison de’tre for the coup. He did not state how he is going to tackle the economic problems facing Sudan even though he did not repudiate any of the existing agreements reached with the multilateral financial institutions and country donors. Nothing can be inferred from all his initial statements that can be interpreted to mean his ideas about the Sudanese State as an “engineering vehicle” or “solution provider” to the whole gamut of contemporary or epochal crisis facing Sudan. Rather, it can be deduced that he see the State as a mercantilist or transactional machine to protect the narrow interests of the military faction that is not interested in democratic rule at all.

The military takeover has effectively and inevitably brought the Sudan’s transition to democracy to a grinding halt despite the assurances by General al-Burhan. The $700 million promised by the United States has been suspended pending the resolution of the crisis. And if the crisis remains unresolved for a long time, there is likelihood that the money will be completely withdrawn and it is very unlikely that any Middle East country or Russia or China will give out such a huge sum for installation of democratic rule.

With all the contradictions clearly thrown up by the coup, nobody can be sure of how they will be resolved. It is, of course, Either-Or. If the military finally gains the upper hand, the contradictions will be “resolved” in its own way by deploying brute force. On the other hand, if the civilians were restored back to power, a very unlikely event, they will have a hard time resolving those contradictions because the military Junkers will resist very stoutly.

Unresolved Contradictions

Indeed something grave must have gone wrong within the Sovereign Council to have not only caused the coup but for the new helmsman, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, not to want to have anything to do with the overthrown Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. This is evident by al-Burhan’s promise to appoint a new “technocratic” Prime Minister as reported by Arab Weekly on October 29, 2021. Bowing down to appoint a “technocratic” Prime Minister is evident of the fact that al-Burhan may not have the expertise knowledge to administer the daily affairs of the State especially the knowledge required to pull the Sudanese economy out of the woods it has been for decades.

According to Arab Weekly, “[a]s international pressure mounted on military rulers to restore a civilian government, Abdel-Fattah Burhan who seized power in a coup this week said the military he heads will appoint a technocratic prime minister to rule alongside it within a week. In an interview with Russia’s state-owned Sputnik news agency published Friday, Burhan said the new premier will form a cabinet that will share leadership of the country with the armed forces. “We have a patriotic duty to lead the people and help them in the transition period until elections are held,” Burhan said in the interview.94

The army chief said that he had installed himself as head of a military council that will rule Sudan until elections in July 2023. The United States and United Nations dialled up the pressure on Sudan’s new military junta as confrontations between soldiers and anti-coup protesters took the death toll to at least 11. After the 15-member U.N. Security Council called for the restoration of Sudan’s civilian-led government, US President Joe Biden said his nation like others stood with the demonstrators. “Together, our message to Sudan’s military authorities is overwhelming and clear: the Sudanese people must be allowed to protest peacefully and the civilian-led transitional government must be restored,” he said in a statement. “The events of recent days are a grave setback, but the United States will continue to stand with the people of Sudan and their non-violent struggle,” said Biden, whose government has frozen aid.95

On Thursday night, Burhan said in a speech to groups who helped remove dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019 that consultations were underway to select a prime minister. He said that the army is negotiating with Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok of the now dissolved transitional council to form the new government. “Until this night, we were sending him people and telling him … complete the path with us, until this meeting with you, we were sending him people to negotiate with him and we are still having hope,” Burhan said. “We told him that we cleaned the stage for you … he is free to form the government, we will not intervene in the government formation, anyone he will bring, we will not intervene at all”.96

Sudan is in the midst of a deep economic crisis with record inflation and shortages of basics. Improvement relies on aid that Western donors say will end unless the coup is reversed. More than half the population is in poverty and child malnutrition stands at 38%, according to the United Nations.97