By Alexander Ekemenah, Chief Analyst, NEXTMONEY

Introduction

“The president of the republic, head of state, supreme head of the army, Idriss Déby Itno, has just breathed his last while defending the territorial integrity on the battlefield. It is with deep bitterness that we announce to the Chadian people the death this Tuesday, April 20, 2021 of the Marshal of Chad,” announced the army spokesman, General Azem Bermandoa Agouna, in a statement read on TV Chad.1

Mr Déby, 68, a career military officer who seized power in 1990 in a coup, was promoted to the rank of Field Marshal last August [2020]. He was re-elected for a six-year term with 79.32% of the votes cast [April 11, 2021], according to provisional results announced … by the national electoral body. Ministers and senior officers said … that the head of state had visited the frontline between his army and a column of rebels who had launched an offensive from rear bases in Libya on Election Day, April 11.2

Today, May 20, marks exactly one month of the sudden death of President or Field Marshal Idriss Deby Itno of Chad. A lot of water has passed under the proverbial bridge in the last one month. The new regime headed by General Mahamat Deby Itno, who happened to be the son of the late President, has ostensibly stabilize itself in power, after throwing away the Constitution of the country that lays out the power structure, dissolution of the Parliament and proposing another general election in the next 18 months (already minus one month!).

Dying by the Bullets

The death of Field Marshal Idriss Deby Itno, the President of Chad who had ruled that unfortunate country with iron fist for the past thirty years did come as a surprise to many watchers of that country and the region. But to keen observers of that country and the region, it may not have come as a surprise because of the inevitability of the ways all dictators, no matter how benevolent they might be perceived, no matter how eulogized or deodorized, end up their lives in disgrace either through violent deaths, kicked out of power like soccer ball, debilitating ailment, etc.

President Idriss Deby Itno did not die as a hero contrary to what have been reportedly presented about his sudden and tragic demise in the media. The military which he helped build into a formidable fighting machine became his deux ex machina to which he was sacrificed like a dog. It was both his stronghold and his Achilles heel. It was a tragic ending.

He shot his way to power in D’Njamena in early December 1990, after overthrowing the then President Hissene Habre, through the barrel of the gun and went out through the same barrel of gun at the battlefront. The seed he sowed more than thirty years ago has grown to consume him. It was the harvest time. In the ripeness of time and at the zenith of his earthly power, he was plucked from pinnacle of power like a rotten fruit that was no longer fit for human consumption. He was consumed in the inferno he stoke through his iron-fisted rule for three decades, suppressing oppositions, mismanaging human and material resources of his country.

He was dispatched to the Greater Beyond with gunshots sustained at the battlefront where he has gone to fight the rebels against his dictatorial government. It was a date with destiny awaiting him but unknown to him.

But in the media reports examined for this review article, Idriss Deby was painted and deodorized as a hybrid dictator, a kind of benevolent leader, for maintaining a tight grip on his country, for helping to maintain “regional stability”, for having a “powerful military” (even stronger than Nigeria!), for doing the biddings of imperialist powers of the West, notably France and the United States, for winning six consecutive presidential elections (until he met his Waterloo at the battlefront) – but without regard to the enormous sufferings of Chadians in the last thirty years under his iron-fisted rule, without economic development of this country despite its considerable rich oil and other solid mineral resources.

It is an irony of life. Idriss Deby won his last (sixth) presidential election without waiting to give his victory speech before rushing to the battlefront where he tragically caught gunshots on April 19, and later died on April 20. What compelled him to rush to the battlefront to confront the rebel group fighting his regime in so shoddy a manner? What happened to his military commanders that he could not rely on them to direct the battle at the frontlines – instead of sticking out his head? Was he persuaded to go to the battlefront so as to entrap him and have him eliminated for reasons yet unknown to us? Who persuaded him to embark on such a reckless or perilous adventure to meet his sudden death? Was he a victim of conspiracy spurned and woven by unknown forces?

There can be no doubt that Deby loved soldiering. He can be considered a modern chevalier, who lived his life to the fullest but at the same gathering sundry enemies against his dictatorial regime over three decades. It is also obvious that he did not apply wisdom, did not look at the crystal ball, did not evaluate the available intelligence before rushing to the battlefront to meet his death. It was a foolhardy adventure that cannot be excused under his love of soldiering.

There can be no doubt that Deby left his country heavily shortchanged. He left his people under constant threat of the jihadist rebels fighting to take over Chad. He left his people in abject poverty with his 31 year-old iron-fisted rule despite the rich resources that could have made his country more stable and prosperous. He preferred to do the biddings of the imperialist West rather than protect the true sovereignty of his country by welding the various ethnic groups in his country together. For this unenviable but tragic achievement, Idriss Deby was being praised to the high heavens by the Western media.

According to The Guardian Editorial: “Déby was not known for democratic or developmental credentials, which is a cause for worry to today’s Chad. For 30 years that he led the oil-rich nation, he fought terrorists as hard as he cracked down on opponents, protesters and even the press. The capital was a seat of daily battles with protesters. In the build up to the last election, public dissenters risked it all with the police. Reports had it that several persons were killed or injured following Déby’s decision to contest for sixth-term. His was a repressive regime for as long as it lasted. And that legacy has survived with the imposition of his son as the next president. Shortly after his death was announced, the government and parliament were immediately dissolved and a military council led by 37-year-old Mahamat Idriss Déby took charge of affairs.”3

He also had Boko Haram insurgents from Nigeria to contend with. He also led the battle against the insurgent group to the chagrin of the Nigerian military High Command. To the eternal shame of Nigeria and its military commanders, Deby was reported to have defeated the insurgents, liberated some territories and handed same back to Nigeria – where the Nigerian military was going forward and backward unable to achieve a decisive victory against the deadly group. The same Boko Haram has now also established its foothold in North west Nigeria, Niger State to be precise, where it has hoisted its flag, collecting revenues from people and ultimately forming a parallel government or dual power in Nigeria. Boko Haram was also reported to be distributing economic palliatives to people in Yobe State during Ramadan. (When a violent non-state actor opposed to the sovereignty of a State goes about doing what it likes without challenge from the State, such a State is finished, technically speaking!)

The impotence, confused ideological and epistemological crisis of the Nigerian State is revealed by the press release issued by the Ministry of External Affairs aftermath the death of Deby, eulogizing his dictatorship and/or despotism, calling him the “true son of Africa”, etc. The raging crisis of the Nigerian State was practically lost on the Federal Government which, at any rate, did not come as a surprise because of the peculiar situation at hand in Nigeria.

Indeed, when the new President, General Mahamat Deby Itno, visited Nigeria on May 14, 2021, President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria received him but failed to condemn the coup that brought Mahamat Deby Itno to power. “President Muhammadu Buhari Friday [May 14, 2021] hosted Chad’s military ruler, Mahamat Deby, in Abuja. At the event, the Nigerian leader did not condemn the coup that brought Mr Deby to power but said Nigeria will assist Chad to stabilize and return to constitutional order.”4

General Mahamat Deby Itno had earlier visited Niger Republic on May 10, 2021 to meet the newly elected President of Niger Republic. During the visit, there were discussions between the two leaders over the security situation in the Sahel region. “Chad’s new leader, General Mahamat Idriss Deby, on Monday, made his first visit to Niger, a fellow Sahel country fighting jihadist insurgents, since coming to power at the head of a military junta after the shock death of his father last month.”5

After arriving in Niamey, the Niger capital, the 37-year-old general held talks with newly elected President Mohamed Bazoum, an aide to Bazoum said. He was then scheduled to head to the west of the country to meet Chadian troops deployed under a regional anti-jihadist mission. Deby “came to see his troops (who are deployed) in Tera, and he used the occasion to hold talks” with Bazoum, the source said, without giving further details.6

Chad has 1,200 troops in western Niger under a five-nation initiative, the G5 Sahel, aimed at pooling military resources to fight an expanding jihadist insurgency in the region. The Chadian military has high standing in the region as a relatively well-equipped and -trained force. Deby, in brief remarks to the Nigerien media, said, “We came here to affirm our friendship… to thank President Bazoum for all his support since the death of Field Marshal (Deby). We also came to show our support for our forces in Tera.”7

Thousands of people have been killed and more than a million have fled their homes since a jihadist revolt began in northern Mali in 2012 and spread to Burkina Faso and Niger in 2015. Niger, the poorest country in the world by the yardstick of the UN’s Human Development Index, is also struggling with jihadist attacks in its southeast, coming from neighbouring Nigeria.8 Bazoum last month was named by the G5 Sahel as a “facilitator” between the new Chadian authorities and FACT.9

It is a strange twist of fate, a strange outworking of the inner political dynamics in Nigeria. Thirty years ago, even till date, Nigeria is nostalgically regarded as the chief hegemon of West Africa, the giant of Africa to be precise. Today, unfortunately Nigeria is a derelict with a disarticulated political leadership, and an incompetent military that cannot defeat Boko Haram rebellious insurgency for the past 12 years or so. It has fallen into destitution of economic poverty amidst plenty compounded by Hobbesian insecurity of lives and properties. Chad, a beggarly nation some thirty years ago now has a powerful military adjudged as one of the best in sub-Sahara Africa.

Alexandre Marc, a Non-resident Senior Fellow at Foreign Policy, Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology, Brookings Institution, captured the prevailing thinking in the corridors of power in Western capitals: “The sudden death on April 19, 2021 of Chadian President Idriss Déby Itno is creating a very dangerous vacuum in Central Africa and the Sahel. Déby, who ruled Chad for 30 years, was killed while fighting rebels trying to overthrow his government.10

“Few sub-Saharan African countries have the regional reach of Chad, and this is due essentially to its army — an army Déby was visiting when he was killed in a firefight, as Chadian troops battled with rebels from Libya. Chad has one of the most effective armies in sub-Saharan Africa and has, over the last 20 years, appeared on all fronts of the war against jihadist groups in the Sahel. It has also been involved in some neighboring civil wars, notably those in Sudan and the Central African Republic (CAR), and more indirectly in Libya.”11

But Marc aknowledges that “Déby built Chad’s powerful army for a few reasons: to protect his regime from the constant ethnic rivalries and ambitions of various warlords from the country’s north; and also to achieve international recognition, credibility, and leverage in order to manage internal politics and use economic resources without interference. Déby always received strong backing from the West, particularly France and the U.S., despite his autocratic rule and rampant government corruption.”12.

“Chad has been the strongest supporter of Barkhane, the French military operation to fight jihadist groups in the Sahel. It has repeatedly sent expeditionary forces into the region and has just positioned more than 1,000 troops in the tri-border region of Liptako-Gourma, where a bloody jihadist insurgency is wreaking havoc on the population and national armies. Chad is also widely recognized as an essential pillar of the G5 Sahel — a military alliance between Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger, and heavily supported by France and the U.S. — to fight the region’s powerful jihadist insurrection. The Chadian army is very familiar with the terrain, as its troops were critically involved in the 2013 French-led military operation to defend Mali from a takeover by well-organized Islamic armed groups. Chad is also one of the top troop contributors to the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, the peacekeeping operation set up in 2013 in Mali in response to the insurrection.”13

“Chad’s military presence in the region is not limited to the Sahel. In 2015, along with troops from neighboring Niger, it played a major role in dislodging Boko Haram from Northern Nigeria. It liberated some large Nigerian cities that had been under the terrorist organization control for months, and struck a near-fatal blow to the organization. In doing so, it shamed the Nigerian army — one of the largest in Africa — that had been paralyzed by Boko Haram for years. Chad continues to fight Boko Haram in and around Lake Chad. Recently, it lost around 100 men in clashes with Boko Haram and one of its splinter groups, the Islamic State in the West Africa Province (ISWAP). In response, it mounted massive offensive and destroyed the camps of these organizations, supposedly killing more than 1,000 militants. At that time, Déby complained bitterly that his army was the only one taking on militants in this region, and threatened to pause all support for the war against terrorist groups outside of his country. These threats were a recurrent strategy to remind the world of Chad’s centrality and to gain support and recognition from Western nations.”14

“Chad also played a role in the conflict in CAR. A few years ago, it got involved with armed groups in CAR’s northeast, assembled under a loose association called Seleka that occupied part of the country. Chad played a role in ending the conflict. Following the 2013 CAR civil war, Chad participated in the U.N. peacekeeping operation, contributing 850 troops, but left after being accused of human rights abuses and of being partial to the Muslim population. The situation was further complicated by members of the Chadian army having commercial interests in CAR linked to cattle raising and trading. In CAR, the Chadian army’s role varies: Sometimes it plays a stabilizing role, and at others it clearly contributes to violence and exactions.”15

“Déby always kept an eye on Darfur, and more broadly on Sudan — mostly for internal security reasons, but Chad also had a strong impact on its neighbor at times. His Zaghawa ethnic group (and of some of his most trusted generals) represents less than 5% of the Chadian population, but is one of the most populous groups in Darfur. Some Chadian Zaghawa people based in Darfur had long been Déby’s most vigorous armed opposition group. To manage his opponents, he made efforts to please Khartoum, while always showing that he could influence the civil war that was ravaging the west of the country through his ethnic and family connections. He did this with the Justice and Equality Movement (MJE), one of the main armed groups opposing President Omar al-Bashir. In 2005, tensions between the two countries became heated, with armed clashes at the border. Twice, armed groups coming from Sudan to overthrow Déby nearly reached the capital, N’Djamena. In response, Déby sent his troops to track the rebels and reached the suburbs of Khartoum, clearly showing that he could bring Chad’s military might to bear.”16

“By the same logic, Déby tried to manage his relations with Libyan groups, and it is understood that he had a good relationship with General Khalifa Haftar. Today, the most active military opposition to Déby’s regime comes from southern Libya (the Fezan), where some Chadian rebels helped General Haftar and where the Goran tribe — which constitutes the majority of the rebels — are active in illicit trading activities. The group that entered Chad and ended up killing Deby last week came from southern Libya; they built up an impressive arsenal, probably through their involvement in the Libyan civil war.”17

Déby’s powerful army is an interesting mix of rebel groups and a modern army, making it very powerful but also highly dependent on Déby’s personal involvement. Most of the high-ranking officers and elite troops are recruited from the northern tribes — principally the Zaghawa, but also the Goran and other groups more broadly known as Toubous. They possess very old and solid combat traditions, excellent knowledge of the desert, an astonishing physical endurance, and a lot of courage. The elite units are often comprised of family and clan members who know each other well. At the same time, the army uses well-trained technicians such as helicopter and combat plane pilots who benefit from heavy support from France and other Western countries. Oil revenues fund generous salaries for officers and elite troops, as well as an impressive arsenal of relatively sophisticated equipment, including combat aircraft and helicopters. The International Crisis Group estimates that 40% to 50% of Chad’s budget goes to the country’s defense and security expenses.”18

In 2000, Chad started to exploit relatively important oil reserves situated in the country’s south. Worried about corruption, the World Bank and a number of development partners set up a complex mechanism by which they would finance an essential pipeline to export the oil to the coast, on the condition that the revenue would be channeled to a special fund monitored by donors. This mechanism was set up to ensure that resources would be used for development and poverty alleviation. At that time, this mechanism was hailed as a great innovation in good governance. But starting in 2006, Déby managed to change the original system to channel significant oil revenues to his army and to large public work programs of his choice, which did not always benefit the poor. Given the regional geopolitics, however, Western donors averted their eyes and accepted the situation.”19

“Despite its strength, the Chadian army also has significant weaknesses that could feed instability. First, the way the army acts toward the civilian population, with frequent exactions, limits its capacity to build up trust in ways that are essential for stability. Second, the army is marred by internal rivalry between commanders. Family rivalries or clan-based rivalries often extend inside the army. The fact that so many of the elite soldiers are northerners means that they also tend to have strong connections to some of the rebel movements based in Sudan or Libya, which are often comprised of former soldiers of the Chadian army. Also, Déby’s strong involvement in the army — which he often commanded directly in the field — is probably the biggest risk. He kept the army’s internal cohesion through personal negotiations, meaning that many loyalties are to him and not to other high-ranking officers.”20

“An additional source of instability is Chad’s tense and fragmented political landscape. Just days before his death, Déby was reelected for a sixth consecutive term, with 80% of the vote; however, his hold on power was largely seen as a parody of democracy. His regime was autocratic, and while a decade ago he was making efforts to accommodate opponents and had some pretense of inclusiveness, his regime is now opaque, with most decisions made by a small group of friends and relatives. Just after his death, a Transitional Military Council was established, with 15 generals all very close to Déby; it is chaired by his son, a 37-year-old general.”21

“The council has suspended the constitution and declared an 18-month transition period. One of the main reasons for the move is certainly the fear that the army could disintegrate, but it is also to ensure that the clan of Déby keeps control of the army and the country. The political opposition and civil society have called the move a military coup and called for protests, as did the African Union. Neither France nor the U.S. said anything immediately, but after protesters died during demonstrations, they weighed in with condemnation of the killing.22

These are very delicate times for Chad and the entire region. The personalization of Déby’s regime has left the country with extremely weak institutions. There is a real risk of serious infighting inside the army and the circles of power, even inside Déby’s own family. Also, tensions with the political opposition are rapidly increasing. It seems clear that suspending the constitution will only make things worse.”23

“France, the European Union, and the U.S. — the main donors to Chad — should put strong pressure on the Transitional Military Council so that it engages in a more substantive dialogue with political factions and civil society than it has done so far. The council should also show that it is serious about organizing elections, as it said it would, much earlier than in 18 months, as announced. Under pressure, the council has just nominated a civilian prime minister. This is a good step. It should also nominate a government sufficiently representative of the country’s different social groups, particularly ethnic groups from the south and center that have been marginalized. It would also be important for Western nations to pressure the new Libyan authorities, particularly General Haftar, to rapidly improve their control of various militias and armed groups in Libya. The ceasefire in this country has created opportunities for highly armed groups to look for opportunities abroad, as was the case when the Gadhafi regime fell.”24

None of the above reasons have bearing or direct impact on the welfare and security of the Chadian people. Conversely, those very reasons helped to stoke the embers of rebellion against his corrupt and ruthless regime. One of the first questions to be asked is this: what shalt it profiteth a country to have a strong military but without strong economy, without security and welfare for the citizens? Deby’s efforts to have total control of the country for his narrow and selfish interests with a powerful military force became his comeopuance, his undoing that sent him to the Greater Beyond. It is perhaps the ways cookies crumble.

But his strong-arm tactics, though eulogized to the high heavens by the Western powers, did not have significant geopolitical bearing and strategic advantage for neighbouring Nigeria where the political conditions are fundamentally different from that of Chad even though there is a rebel insurgent group also fighting the Nigerian State and the domination of the Hausa-Fulani oligarchy or Caliphate. While the Nigerian democracy has thrown up different personalities as leaders from 1999 to date, Chad has been tragically stuck with the same man for six consecutive elections. While both countries have gone through different political trajectories they have also found a common ground in their respective task of combating internal rebellion stoked primarily by failure of democratic governance in both countries. Unfortunately, their joint collaboration especially in fighting the deadly Boko Haram insurgency and the encroachment of climate change in the Lake Chad Basin has been a resounding failure.

Chad had not known true or genuine democratic rule for the past thirty or more years. It has always been a one-man or one-party rule because Deby and Habre before him had always make sure the opposition or all oppositions are stifled under severe political repressions. Where, in historical comparisons, Ibrahim Babangida in 1993 and Sani Abacha in 1998 failed to impose their hybrid dictatorship by transforming from military leaders to civilian leaders, Habre and Deby succeeded beyond all expectations to transform from military to civilian leaders. However, this came at huge expense of the country that was inevitably plunged into quagmire of abject poverty and destitution. Habre and Deby were not transforming development leadership!

Mystery Death

There were many questions surrounding Mr. Déby’s death, including how exactly he was killed and whether and why he was visiting an area where conflict was raging.25

The circumstances in which Deby was shot at the battlefront on April 19 and the gunshots from which he later died the following day, April 20, in D’Njamena remain shrouded in mystery or secrecy as no precise information has been made available by the Chadian authorities except the official announcement of his death.

However, the understanding of these circumstances must be linked with the political dynamics that have been at play over the past one year or so before he met his Waterloo at the battlefront.

First, the fact that Deby took the title of Field Marshal of the Chadian military or the political Generalismo of the Republic eight months earlier, in August 2020, before his death clearly indicated that he did not want to leave power peacefully at all. He wanted to die in power. And he did die in power, violently, felled by bullets at the battlefront.

Second, the fact that Deby decided to contest the presidential election for the sixth consecutive term is also an additional indication that his greed for power remain untrammeled and unparalleled, similar to all other African dictators who clung to power until they died in power or got thrown out in social upheavals and/or revolutions. This indicator was ignored in the analysis of the holistic situation that framed his death. This indicator or factor itself is a trigger in the network of circumstances that led to his death.

The mystery, however, is how he died. Nobody seems to know precisely how he died as this seemed to have been classified by the Chadian authorities. How did he die? Did he die by bullets from the gunfires of the rebels? Or did he die from friendly fires i.e. from his own troops? What exactly did France know about his death? Was Deby a victim of coup de’tat executed at the battlefront but neatly packaged and presented as “death by gunshots he sustained at the battlefront”? Are there certain power blocs within the Chadian military or political class that got tired of Deby’s misrule of three decades and wanted him out of the way at all costs? Is his son, General Mahamat Deby Itno part of this conspiracy or power blocs despite the pretence to the contrary – given his sinister silence so far? (Idris Deby Itno had many wives and children. Therefore this might not be an insignificant factor in his sudden death.)

If the pattern of toppling of African dictators in the last two decades or so can be any guide to the understanding of what has happened to Deby in Chad, then it can be safely argued that Deby was a victim of wider conspiracy that is yet to be unravelled. The refusal of the current Chadian authorities interestingly led by Deby’s son, General Mahamat Deby Itno, to disclose how Deby died lend credence to this conspiracy theory. The lack of reprisal for the killing is an indication that Deby died by consensus at the battlefront. This line of reasoning can be escalated or extended further. With the degree of involvement of France in the internal affairs of Chad militarily (including espionage or intelligence gathering), politically, and socioeconomically, it cannot claim ignorance of what happened to Deby at the battlefront. There is no plausible deniability for France because of its stanglehold over Chad.

All that the media regalled the public with was that Deby died from gunshots sustained at the battlefront while directing offensive against the rebels fighting against his regime – but not the details of how he sustained those gunshots. There were no details where the gunshots came from.

Killed while directing an offensive against the armed group FACT, which had entered Chad through southern Libya, the late president Idriss Déby had always known that his power was coveted by and under threat from rebel movements, many of which established rear bases in Libya or Sudan. Here we break down the groups since his rise to power.26

Much like his forerunners, Idriss Déby, who became president of Chad through a military coup in late 1990, had to contend with rebel groups early on in his rule. In 1995, the president’s former army chief of staff, Mahamat Garfa, took up arms against him with the help of his nephew, Mahamat Nour Abdelkerim.27

Ultimately killed on 18 [?] April in Kanem region, Déby had always known that his power was under threat from rebels, most of whom were welcomed or even supported by neighbouring countries, Libya and Sudan chief among them.28

There have been a few close calls, like in May 2005 when Abdelkerim’s forces nearly captured the capital, N’Djamena. And in February 2008, Déby, at the ready to fight, decided to confront Mahamat Nouri’s troops in Massaguet, a city 80 kilometres north-east of N’Djamena. In the end, the rebels were forced to retreat, but his presidency had come close to being upended.29

Re-elected six times, President Déby never went unchallenged. But the 2011 collapse of Muammar Gaddafi’s rule in Libya only added to the climate of instability. Since 2018, he had been grappling with a new wave of rebel movements coming from northern Chad.30

According to Mahamat Adamou, Ruth Maclean, Declan Walsh and Eric Schmitt, writing in the New York Times: “Mr. Déby had been scheduled to give a victory speech on Monday to celebrate winning his sixth term in office, but his campaign director said that he had instead decided to visit Chadian soldiers battling insurgents advancing on Ndjamena.”31

On the same day as the presidential election, April 11, rebels crossed the northern border from Libya, according to local media outlets. Those rebels, from a group called the Front for Change and Concord in Chad (F.A.C.T., by its French acronym), moved southward in several columns and claimed to have “liberated” a province of the country last week.32

They reportedly beat a retreat to the north on Monday night after reports of heavy losses on both rebel and government sides. The government’s spokesman said the rebels’ “adventure had come to an end,” but the group said it had killed or wounded 15 top-ranking army officers, and was merely regrouping.33

On Tuesday night, the F.A.C.T. rebel group announced on Twitter that its forces were on their way to the capital. Kingabe Ogouzeimi de Tapol, a spokesman for the group, said, “Chad is not a monarchy. There cannot be any dynastic devolution of power in our country.”34

A French official with long experience in the Sahel said on Tuesday that Mr. Déby had been in the north participating in the fight against the rebels. “We’ll never know if he was injured by a rebel bullet or by simply falling from his command car,” the official said, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss delicate security issues.35

Testifying to Congress in Washington on Tuesday, Gen. Stephen Townsend, the top American commander for Africa, said the circumstances surrounding Mr. Déby’s death were very murky.36 “He’s a retired general, and he has in the past, gone to the front,” General Townsend told the House Armed Services Committee. “We don’t know exactly how he got killed.”37

General Townsend said that a combination of Chadian and French forces confronted a rebel column, and as it appeared to be withdrawing, Mr. Déby was killed. Several analysts said that the dramatic ouster of Mr. Déby, one of Africa’s most entrenched autocrats, appeared to be a self-inflicted error by France.38

According to Mathieu Olivier and Vincent Duhem: Saturday 17 April. Night has fallen on N’Djamena and most Chadians have only one thing on their minds: breaking the Ramadan fast, which began less than a week earlier. Idriss Déby Itno (IDI) is thinking of something else. Since 11 April, columns of rebels have entered Chadian territory from Libya.39

According to the latest French and Chadian intelligence in his possession, the rebels of the Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT) had made a breakthrough in Kanem. They are north of the town of Mao, some 300 kilometres from the capital.40

The Marshal has sent reinforcements, but the insurgents are well armed and have military equipment, some of it Russian, amassed in Libya. IDI has his doubts. As is often the case, he decides to go to the front. As in 2020 on the shores of Lake Chad, he intends to show himself and galvanise his troops.41

At the stroke of 10pm, he climbs aboard an armoured Toyota vehicle.42

According to one report, the soldiers were attacked by militants from the Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT) who had arrived from their base in Libya and had entered Chadian soil on 11 April. Their stated goal was to rid the country of Déby’s 31 years of power.43

In an interview with Radio-France Internationale, Mahamat Mahadi Ali, the rebel leader of FACT, said Déby had attended the battle on Sunday and Monday (18 and 19 April), where the fighting was taking place in the centre-west of the country, near Nokou in Kanem. Déby was reportedly wounded on the battlefield on Sunday, and was then flown to the capital 400km way by helicopter.44

From the above narratives, it is very clear that nobody is willing to disclose how Idriss Deby died at the warfront. Not even his son who now took over as the Chadian leader. That in itself is a great disservice to the memory of Deby, whatever anybody wish to remember about him. The Chadian authorities have created an impression that they do not care about the death of Deby; they do not care about what the public think of his death; that it does not matter how he died or that he is not indispensable after all, etc. This is rather unfortunate for a man who had ruled his country for three decades.

But if we follow the descriptive analysis of some of the experts quoted, it is quite possible to create the scenario of how he might have been shot at the battlefront. First, if the French official with long experience in the Sahel quoted above is anything to reckon with, then it is possible that Deby was killed by the rebel troops. On the other hand, if he had fallen off the command car then he could have been shot from either side or he fell off as a result of physical exhaustion.

Second, General Stephen Townsend, the top American commander for Africa, seems to be suggesting that Deby might might have been shot at the back while withdrawn from the battle field alongside French forces.

Nobody is really sure of what happened to Deby. But several analysts are suspicious that he might have been upstaged at the battlefront with the connivance of the French.

Magnetic Pole of Attraction

Deby and Chad provide modern case study of how not to be a neocolony for former colonial overlord. In this scenario stands France with its powerful military providing all technical advisories to Idriss Deby Itno since he took power in early December 1990. And through Deby, France has been technically milking Chad dry in its resources and holding the country hostage to French imperialism and its selfish interests.

The military-political relationship between Deby and France can be gleaned from Wikipedia.

After attending the Qur’anic School in Tine, Déby studied at the École Française in Fada and at the Franco-Arab school (Lycée Franco-Arabe) in Abeche. He also attended the Lycée Jacques Moudeina in Bongor and held a bachelor’s degree in science.45

After finishing school, he entered the Officers’ School in N’Djamena. From there he was sent to France for training, returning to Chad in 1976 with a professional pilot certificate. He remained loyal to the army and President Felix Malloum even after Chad’s central authority crumbled in 1979. He returned from France in February 1979 and found Chad had become a battleground for many armed groups. Déby tied his fortunes to those of Hissene Habre, one of the chief Chadian warlords. A year after Habre became president in 1982, Déby was made commander-in-chief of the army.46

He distinguished himself in 1984 by destroying pro-Libyan forces in eastern Chad. In 1985, Habré sent him to Paris to follow a course at the Ecole de Guerre and upon his return in 1986, he was made chief military advisor to the president. In 1987, he confronted Libyan forces on the field, with the help of France in the so-called “Toyota War”, adopting tactics that inflicted heavy losses on enemy forces. During the war, he also led a raid on Maaten al-Sarra Air Base in Kufrah, in Libyan territory. A rift emerged on 1 April 1989 between Habré and Déby over the increasing power of the Presidential Guard.47

In short, Deby was breast-fed and baby-sitted by France to the point where he became no more than a puppet. That is why French President Emmanuel Macron was shedding crocodile tears during the funeral of Deby.

Western media ignored the escalating geopolitical crisis in North Africa (in the Magreb to be specific) over the last two decades or so that threw up Islamic fundamentalism and jihadism which spread to West Africa (including Nigeria through Boko Haram) and Central Africa. This geopolitical crisis consumed Libya, Mali, and to a large extent too, Tunisia and Egypt, causing toppling of age-long dictators in these countries. This same crisis spread to Chad and widened the rifts among the various ethnic groups and tribal clans in the country. This was what generated both political crisis and jihadist wars being waged against Deby’s government by various rebel groups notably the

Libya-based Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT).

Even though Deby had been able to cling to power for over three decades he cannot be said to have known peace. He was constantly at the battlefield fighting for his regime survival. He succeeded to a very large until luck ran out on him. He cannot be said to have achieved any other major feat that impacted significantly on the lives and welfare of ordinary Chadians. He built a powerful military that is the backbone of his power base and also part of the ruling political class in Chad. But this brutal class, though riven with internal dissensions, only succeeded in holding down economic development of Chad.

As part of the geopolitical and strategic game for his regime survival, Deby wisely signed into the global war on terrorism launched by the United States and her allies aftermath the September 11 attack on the US by Al Qa’eda in 2001. He therefore became a darling boy to the West. As a result of this, Deby had no choice than to stand and wage war against Islamic extremism and through mounting repression against perceived political enemies within and outside Chad.

Deby’s wars against Islamist extremists in West and Central Africa and heavily supported by Western power is seen to be the main attraction for the West. But that is a cover for the exploitation of Chad’s natural resources and wealth which Deby allowed to take place without resistance. The oil resource is cornered by Western multinational oil corporations. Its strategic solid mineral resources are also highly coveted by the West especially France that has become the grandmaster of the Chadian political scenario over the years.

Deby was solidly backed by former colonial power France, which in 2008 and in 2019 used military force to help defeat rebels who tried to oust him. “We safeguarded an absolutely major ally in the struggle against terrorism in the Sahel,” French Defence Minister Florence Parly told parliament in 2019.48

Deby supported French intervention in northern Mali in 2013 to repel jihadists, and the following year stepped in to end chaos in the Central African Republic. Experts consider Chadian soldiers the strongest in the G5 Sahel – the regional bloc transformed into a military alliance at Paris’ behest in 2017, bringing together forces from Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso and Mauritania. In 2015, Deby launched a regional offensive in Cameroon, Nigeria and Niger against Nigeria-based Boko Haram jihadists, dubbing the Islamic State affiliate “a horde of crazies and drug addicts”.49

Deby’s power base, the army, comprises mainly troops from the president’s Zaghawa ethnic group and is commanded by loyalists. It is considered one of the best in Sahel. According to the International Crisis Group think tank, defence spending accounts for between 30 and 40 percent of Chad’s annual budget.50 The late president also named relatives and cronies to key positions, and failed to address the poverty that afflicts many of Chad’s 13 million people despite oil wealth.51 The country ranks 187th out of 189 in the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI).52

Marielle Debos gave a quick run-down of French engagement in Chad in the last few years.

Between 3 and 6 February [2019], the French army launched airstrikes against a rebel convoy in Chad. The intervention came at the request of Chadian authorities, who welcomed France’s cooperation and the “neutralisation” of the fighters.53

Considering the long history of French involvement in its former African colonies, there is nothing exceptional about these strikes. In fact, Chad has experienced more French military interventions since independence than any other African country.54

But the justifications for France’s presence and the military techniques have changed recently in important ways.55 In the 1960s and 1970s, the former colonial power waged a counter-insurgency war against the Chad National Liberation Front (Frolinat). In 1986, France then established Operation Epervier (Sparrow Hawk) to contain Libyan expansionism. Chadian dictator Hissène Habré – who was sentenced in 2017 for war crimes, crimes against humanity and torture – was a key ally of France and the US against Gaddafi.56

Then as now, France supported the existing regime in the name of “stability”, and over the decades, France’s military presence has allowed it to prop up subsequent regimes in Chad. They first supported Habré before switching allegiance to Idriss Déby who has been president since seizing power with French support in 1990.57 Since then, Déby has faced several serious rebellions. In both April 2006 and February 2008, rebels even managed to reach the capital N’Djamena. France’s support at these times was more discreet than today. It involved sharing intelligence with the Chadian army, “shows of force” (low-level flight over the rebel column) and warning shots. In 2008, it also included facilitating the supply of ammunition from Libya and protecting the capital’s airport.58

In 2019, however, the French approach has changed significantly. They are no longer content to create conditions favourable to a victory for the Chadian army: they launch airstrikes against rebels themselves.59France’s Operation Epervier remained active despite the resolution of the Chad-Libya conflict and the end of the Cold War until it was replaced in August 2014 by Operation Barkhane. This new French initiative absorbed Epervier in Chad and Operation Serval in Mali. With approximately 4,500 soldiers deployed in five Sahelian countries, Barkhane is currently the largest French deployment abroad.60

Barkhane’s objective is to support the “war on terror” in the Sahel and Sahara. However, its most recent targets have been rebels attempting to seize power in N’Djamena. These Chadian fighters are far from nice democrats. They use the rhetoric of democracy and change, but many were close to Déby before their defection. Timan Erdimi, leader of the Union of Resistance Forces (UFR), who happens to be the president’s cousin, was a pillar of the regime until he joined the rebellion in 2004.61

Whatever we think of their past and current politics, however, the UFR has little to do with the jihadist armed groups in the Sahel and Lake Chad basin that France is purportedly in the region to combat. Chadian rebels, who found refuge in Libya and made alliances with other armed groups there and in Sudan, are driven by politics not ideology.62

From a legal point of view, France’s February intervention falls within the framework of a military cooperation agreement dating back to 1976 since when it has been interpreted excessively broadly. But unless we believe that anything that helps Déby is part of the fight against terrorism, there is little connection between France’s February airstrikes and Barkhane’s raison d’être.63

Chadian authorities have strategically instrumentalised the “war on terror” by rebranding rebels as “mercenaries and terrorists”. Since its army’s intervention alongside the French in Mali in 2013, Déby has also played up the military diplomacy card and made himself indispensable to Western allies. As a result, the conflict-ridden country has acquired the status of regional power in just a few years.64

Chad’s army is currently engaged in the war against jihadist armed groups in the Sahel and Boko Haram in the Lake Chad basin. It is now badly overstretched, however, and is facing difficulties in trying to cope with a rebellion on its own territory. This is especially the case as many soldiers and rebels have been recruited among the same ethnic groups and share strong social ties.65

This is why France’s airstrikes are particularly important. They are part of an escalation and are a sign that France is now supporting Déby at all costs while ignoring the regime’s authoritarian practices and human rights violations.66 In France, this means very little. Debates on foreign policy and its consequences in the Sahel are staggeringly poor. Few French MPs have voiced concern over the strikes. But in Chad, the role of the former colonial power does not go unnoticed and continues to fuel a strong anti-French sentiment.67

According to Mahamat Adamou, Ruth Maclean, Declan Walsh and Eric Schmitt, writing in the New York Times: “Chad is a desert nation three times the size of California, surrounded on all sides by countries facing serious instability, like Libya, to the north, and Nigeria to the south. Its military forces have been key to both the war in the Sahel, a vast stretch of territory to the south of the Sahara, and the fight against Boko Haram and its splinter groups in the Lake Chad region.”68 “For that reason, Mr. Déby enjoyed the support of France and the United States, despite the repression of his political opponents and many accusations of human rights violations.”69

American officials have mostly ignored complaints that Mr. Déby has overseen an authoritarian regime, Africa experts said, in large part because of his staunch support for counterterrorism operations.70

Chad’s military has worked closely with Americans, playing host to exercises conducted by the United States. The U.S. military now has fewer than 70 troops in Chad, mostly training and equipping Chadian military and counterterrorism forces, said Col. Christopher Karns, a spokesman for the Pentagon’s Africa Command. “Chad’s ability to contribute to regional security initiatives helps reduce instability in the region,” Colonel Karns said in an email.71

Over the three decades since Mr. Déby seized power from Mr. Habré, he faced other threats to his rule. Rebels led by Mr. Déby’s nephew reached the capital in 2006 and 2008. The president’s forces fought them off, with the “discreet” support of France, according to who study Chad.72

But in 2019, when Chad asked the French force in the Sahel for help in dealing with another incursion, Paris was less discreet about the support, and obliged by launching a series of airstrikes on the rebels. Jean-Yves Le Drian, the French foreign minister, told Parliament at the time, “France intervened militarily to prevent a coup d’état.”73

Petrodollars

While it is true that the fight against Islamic extremism and jihadism is geopolitically significant to both the United States and France, a fight that is part and parcel of the global war on terror since 2001, petrodollars are perhaps the most attractive point for the Western powers in their involvement in Chad even though the petroleum industry in Chad is not yet fully developed.

Chad ranks as the tenth-largest oil reserve holder among African countries, with 1.5 billion barrels of proven reserves as of 2018 and production of over 140,000 barrels per day in 2020. Petroleum is Chad’s primary source of public revenue, and around 90 percent of oil production is exported.

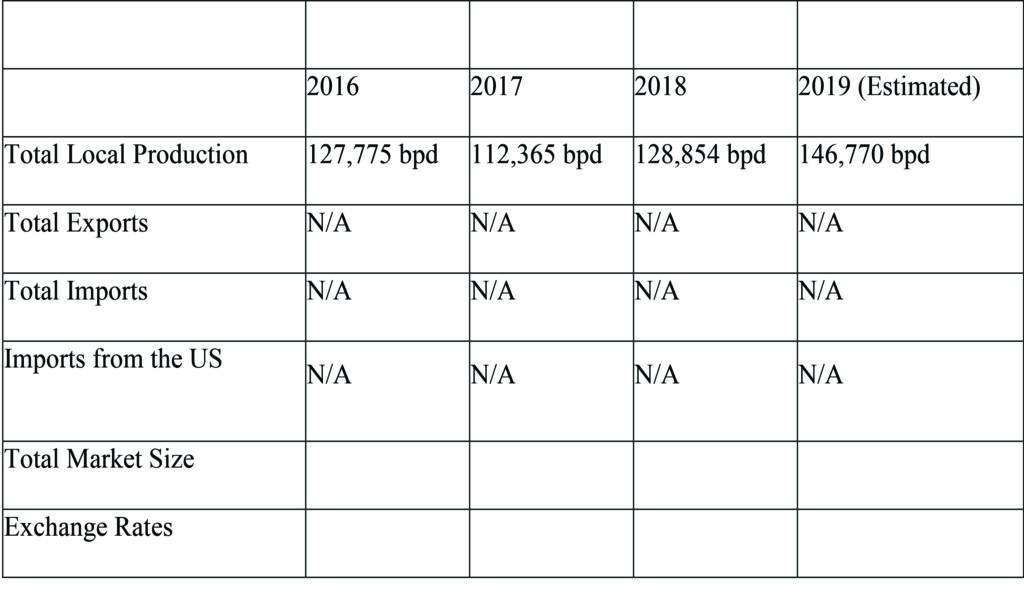

Chad is a leading producer of crude oil in Central Africa. International companies, represented by the Esso Exploration & Production Chad Inc (EEPCI), the China National Petroleum Corporation International (CNPCI) and the Glencore consortiums, are key actors in the exploration, production and refining of oil, alongside the Hydrocarbons Company of Chad (Société des Hydrocarbures du Tchad, SHT). Its nascent gold sector is primarily artisanal, alongside industrial mining of limestone. Chad however ranks 187 out of 189 countries in the United Nations Development Programme’s 2019 human development index. Social conflicts and public debate have arisen around the management of oil revenues, including the oil-backed loans granted by Glencore in 2013 and 2014, environmental impact of extractive industries and poverty alleviation.74

Chad was the first country to include oil transport (the Chad-Cameroon pipeline) and refining (the Djermaya refinery) in the scope of its EITI reporting. This led to better public understanding of the midstream hydrocarbons sector. Chad EITI pioneered efforts to publicly disclose information about the terms of the oil-backed loans granted by Glencore, showing that most of Chad’s revenues from the oil sector were primarily directed to reimbursing the loan. Chad also participates in the EITI’s targeted efforts on commodity trading, achieving progress in disclosing information about the sale of the government’s shares of oil. The government is also starting to open up its own systems, with detailed quarterly notes about the oil sector on the Ministry of Finance website and access to SHT’s audited financial statements. After the government committed to disclosing all oil and gas contracts in April 2018, Chad EITI published them online. In december 2020 the EITI in Chad published an EITI report under flexible reporting for the 2018 fiscal year.75

Chad ranks as the tenth-largest oil reserve holder among African countries, with 1.5 billion barrels of proven reserves as of January 1, 2013. Petroleum is Chad’s primary source of public revenue, contributing approximately 60 percent of the national budget. Chad’s petroleum exports are produced primarily by the Esso Exploration & Production Chad Inc. (EEPCI) consortium and the China National Petroleum Company in Chad (CNPCIC). EEPCI signed a new agreement with the GOC to extend its operations until 2050. There are small oil companies doing exploration projects on new blocs. The Esso consortium began extracting oil from southern Chad in 2003. The 1,100 km Chad-Cameroon pipeline carries Chadian oil exports through Cameroon to the port of Douala. Canadian, British, Taiwanese, Russian, and Nigerian companies are currently working towards exporting oil from their respective fields via the consortium’s Chad-Cameroon pipeline. A joint venture between the Government of Chad’s state-owned oil company, Societé des Hydrocarbures du Tchad (SHT), and the CNPCIC refines petroleum for export and domestic consumption at a 20,000 barrel-per-day refinery 40 km outside N’Djamena.76

Chad’s mining sector is underdeveloped and the country’s mineral resources are under-explored. The only mineral currently exported from Chad is sodium carbonate, also known as natron. According to a 2010 geologic survey by the Government of Chad, Chad may contain deposits of gold, silver, diamonds, quartz, bauxite, granite, tin, tungsten, uranium, limestone, sand, gravel, kaolin, and salt.77

The Government of Chad created the National Mining and Geology Company (SONAMIG) with the aim to boost the mining sector that remained unexplored and unexploited. The SONAMIG allows the State to organize and to manage minerals through mining protection, realization of the geological mapping and mining inventory projects, rational financial mobilization and the establishment of the counters for the Gold trade.78

Chad’s natural gas sector is also largely underdeveloped. Less than 1 percent of Chad’s 999.5 billion cubic meters of proven natural gas reserves are exploited for domestic consumption, Chad is not an exporter of natural gas.79

Although the full hydrocarbon potential of the landlocked West African country of Chad has still to be fully assessed, discoveries during the 1990s show the existence of viable oil reserves. The Komé, Miandoum, Bolobo and Sédigi oil fields could produce an estimated 150,000 barrels per day. However whether they are ever developed depends entirely on whether the crude pipeline from Chad to the coast of Cameroon is ever developed. There is the potential for a viable upstream oil industry.80

The downstream oil industry is dependent on the importation of refined petroleum products from neighbouring Nigeria and Cameroon. Oil-derived products supply the majority of the country’s commercial energy needs. The Sedigi project, if it goes ahead however, could supply all Chad’s petroleum requirements.81

Chad has proven recoverable oil reserves estimated at approximately one billion barrels and has the potential to be a significant energy producer with a viable upstream industry.82

Oil exploration began in the 1970’s and several early discoveries were made in both the Lake Chad Basin and the Doba Basin in southern Chad by a consortium comprising Chevron, Conoco, ExxonMobil and Shell. (Ibid)Exploration and development activities were suspended due to the outbreak of civil war in 1979. After Conoco withdrew from Chad in 1981, Exxon took over operations and discovered the Bolobo field in 1989. Chevron sold its stake to Elf Aquitaine in 1993.83

Since November 1996, however, there have been renewed efforts to implement projects to develop and transport crude from the oilfields in Chad. The Chad to Cameroon Pipeline which is anticipated to cost in the region of US$ 3.5 billion is a project designed to produce from the oilfields in the Doba Basin and transport the crude by pipeline through Cameroon to Kribe offshore terminal.84

Another project plans to make Chad self sufficient with respect to oil products by building a small refinery in N’Djamena to process the product from the Sedigi oilfield in the Lake Chad Basin.85

In addition to the planned exploitation of these fields exploration activities have continued. In 1999, three companies, US-based Trinity Gas and Carlton Energy, and Nigerian Oriental Energy Resources signed an exploration agreement with the Chad government for Block H. Block H is 430,000 square kilometres and the group plans to spend $59 million on exploration.86

Despite having proven oil reserves, Chad has no facilities for the production or refining of its own oil and is therefore totally dependent on fuel imports mainly from neighbouring Nigeria and Cameroon.87 Oil-derived products supply the majority of the country’s commercial energy needs. Current estimates of consumption of petroleum products include the quantity of products that are smuggled from Nigeria where the prices are lower. Oil consumption in 1998, is estimated at 1,200 bpd.88

Refinery production problems in Nigeria and Cameroon caused fuel shortages and the prices to rise in Chad. Distribution and marketing of fuels and lubricants products is carried out by local private Chadian companies as well as Shell (25%), Mobil (20%) and TotalFinaElf (20%).89

Thus it can be seen how the oil sector has gone through its own internal evolution over the arch of time and space, the role played and is still being played by multinational oil corporations considering the fact that the sector is totally dependent on oil exploration and prospecting by the multinational oil corporations notably from the United States, France and recently China.

Thus it can also be seen how Chadian oil sector is intricately connected with that of multinational oil corporations, geopolitical relationships with neighbouring countries especially Nigeria, Cameroon and Niger. Lake Chad Basin is particularly interesting in the scenario it represent and has presented in connection with Nigeria. Here we see the reason why Chad is vehemently opposed to Boko Haram insurgency because of the threat it presents to Lake Chad Basin and its oil potential to both Nigeria and Chad, including Cameroon.

The Doba region and Lake Chad Basin are particular flashpoints. This is why the battle for military victory and supremacy is most fierce, for instance, in Lake Chad Basin between the Nigerian military, the Chadian military on the one hand and Boko Haram insurgents on the other hand.

According to Remadji Hoinathy (2020): On 23 March [2020], Jama’atu Ahlis-Sunnah Lidda’Awati Wal-Jihad (JAS) [or Boko Haram] attacked an army position in Boma, a Chadian peninsula on the Lake Chad Basin. Ninety-eight Chadian soldiers were killed – the most ever in an attack. Around 40 were wounded and military equipment was captured. Chad’s retaliation was as unprecedented as the JAS attack. The Wrath of Boma military campaign spans three countries – Chad, Niger and Nigeria.90

The Boma attack confirms that JAS remains as formidable a foe to the Lake Chad Basin countries as the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). More than eight hours of fighting on a swampy semi-island with heavy casualties for Chad demonstrates JAS’s combat capacity, which included significant amphibious equipment, diligent planning and meticulous intelligence work.91

It also shows that the JAS and ISWAP operational sectors often intersect and overlap. The sub-faction of JAS led by Ibrahim Bakura, operating around the northern part of the lake, has since 2019 allowed JAS leader AbubakarShekau to extend his area of operation beyond Southern Borno in Nigeria, into Niger and Chad.92

On the same day as the Boma attack, a Nigerian army unit was ambushed by ISWAP in the Konduga area in Borno State, resulting in around 100 casualties. A Nigerien military reconnaissance outpost in Chetima Wangou, Diffa Region, was attacked two weeks earlier, resulting in eight deaths.93

Attacks for resupply and hostage-taking for ransom have persisted across the Lake Chad Basin, but assaults on military positions have intensified across the region since March 2020. These events are part of a trend since the last quarter of 2018 that show the resilience of Boko Haram factions, particularly ISWAP.94

Recent attacks on civilians and humanitarian actors in the region have raised concerns about JAS’s enduring capacity to execute large-scale assaults. Since Boko Haram splintered in August 2016 and its strategic camp in the Sambisa Forest was dismantled in December that year, JAS was thought to have been diminished, disorganised and confined to Southern Borno.95

Persistent attacks have also raised questions about the effectiveness of the Lake Chad Basin states’ responses to eradicate Boko Haram. The ability of governments in the region to enhance their legitimacy and deliver much-needed services to their communities has also come under scrutiny.96

In March this year, before engaging in Lake Chad’s swamps and islands, Chad obtained agreement from Niger and Nigeria for its troops to deploy on their territory. Niger and Nigeria also agreed to block their respective territorial lake shores to prevent JAS fighters from fleeing. This large-scale military response has Shekau’s troops on the run, as is clear in his audio message from 11 April urging his troops to stand firm.97

In 2000, with the north/south dispute quelled, Déby’s government started building the country’s first oil pipeline, the 1,070 kilometer Chad-Cameroon project. The pipeline was completed in 2003 and praised by the World Bank as “an unprecedented framework to transform oil wealth into direct benefits for the poor, the vulnerable and the environment”.98

Oil exploitation in the southern Doba region began in June 2000, with World Bank Board approval to finance a small portion of a project, the Chad-Cameroon Petroleum Development Project, aimed at transport of Chadian crude through a 1000-km buried pipeline through Cameroon to the Gulf of Guinea. The project established unique mechanisms for World Bank, private sector, government, and civil society collaboration to guarantee that future oil revenues benefit populations and result in poverty alleviation.99

However, with Chad receiving only 12.5% of profits from oil production, and the agreement for these revenues to be deposited into a London-based Citibank escrow account monitored by an independent body to ensure the funds were used for public services and development, not much wealth was immediately transferred to the country. In 2006, Déby made international news after calling for his country to have a 60 percent stake in the Chad-Cameroon oil output after receiving “crumbs” from foreign companies running the industry. He said Chevron and Petronas were refusing to pay taxes totalling $486.2 million. Chad passed a World Bank-backed oil revenues law that required most of its oil revenue to be allocated to health, education, and infrastructure projects. The World Bank had previously frozen an oil revenue account in a dispute over how Chad spent its oil profits, with Déby accused of using the funds to consolidate his power. Déby rejected those claims, arguing that the country does not receive nearly enough royalties to make meaningful change in the fight against poverty.100

Chad’s recent history, under Déby’s leadership, has been characterized as having been rife with endemic corruption and a deeply entrenched patronage system that permeated society, according to Transparency International. The recent exploitation of oil has fueled corruption, as revenues have been misused by the government to strengthen its armed forces and reward its cronies, which contributes to the undermining of the country’s governance system. In 2006, Chad was placed at the top of the list of the world’s most corrupt nations by Forbes magazine, In 2012, Déby launched a nationwide anticorruption campaign called Operation Cobra, which reportedly recovered some $50 million in embezzled funds Nongovernmental organizations say, however, that Déby has used such initiatives to punish rivals and reward cronies.As of 2016, Transparency International ranked Chad 147 out of 168 nations on its corruption index.101

Faced with a growing threat from Boko Haram, Déby increased Chad’s participation in the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), a combined multinational formation comprising units from Niger, Nigeria, Benin, and Cameroon.In August 2015, Déby claimed in an interview that the MNJTF has successfully “decapitated” Boko Haram.102

In January 2016, Déby succeeded Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe to become the chairman of the African Union for a one-year term. Upon his inauguration, Déby told presidents that conflicts around the continent had to end “Through diplomacy or by force… We must put an end to these tragedies of our time. We cannot make progress and talk of development if part of our body is sick. We should be the main actors in the search for solution to Africa’s crises”.One of Déby’s first priorities was to accelerate the fight against Boko Haram. On 4 March, the African Union agreed to expand the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) to 10,000 troops.103

In 2017 the US Justice Department accused Deby for accepting $2 million bribe in return for providing a People’s Republic of China company with an opportunity to obtain oil rights in Chad without international competition.104

According to a market survey: The Chadian oil and gas market is expected to register a CAGR of more than 0.54 % during the forecast period of 2020 – 2025. Factors, such as increasing investments and increasing production of gas in the country, are expected to boost the demand in the Chadian oil and gas market during the forecast period. However, issues, such as political instability and terrorism in the country, are impeding the growth of the oil and gas sector.105

- The midstream sector in Chad is expected to witness significant growth in the forecast period. Investment in the midstream infrastructure is likely to boost the midstream sector, in the country, in the coming years.

- Investment is being made into the exploration and production of oil reserves in the country. The investment is expected to continue in the forecast period. It is likely to act as an opportunity for the midstream and downstream players in the country’s oil and gas market.

- Decreasing oil production is expected to act as a restraint and impede the growth of the Chadian oil and gas market. Low proven reserves of oil are also expected to act as a hindrance for growth of the sector.

- The pipelines are mostly clustered in the southern region of the country, with one of the pipelines connecting Cameroon with Chad. Few proposals are in the initial stage and may get approved during the forecast period.

- Niger-Chad oil pipeline is a proposed oil pipeline in Central Africa. It was expected to be fully completed by 2019, but due to economic viability issues, little progress has been made. The pipeline is expected to maintain a capacity of 60,000 barrels per day.

- The Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline is an oil pipeline in Central Africa that runs from Doba Basin, Chad, to Kribi, Cameroon. The pipeline has a length of 1,070 kilometers and has a capacity of 225,000 barrels per day.

- Hence, the midstream sector is expected to witness significant growth in the forecast period, due to the increasing investment in the midstream infrastructure.106

The US, France and other superpowers are most probably not in Chad to protect Deby’s authoritarian regime but to protect their investments in the oil and gas industry that is just coming into being in that country and open up opportunities for prospecting for more resources especially solid mineral resources that are of strategic values to them which Chad could not mine on its own and turn to booming industries like most other African countries.

Yet Deby had enjoyed the protection of the Western superpowers in this case precisely because he was able to latch on to this opportunity and hold his country in his tight grip of iron-fisted rule for the past thirty years. The logics fitted themselves neatly and perfectly into each other aided and abetted by favourable geopolitical dynamics in the region – or the ability to turn and/or manipulate those dynamics in his favour over the last three decades.

However, beneath this perfect-looking surface or landscape of favourable geopolitical dynamics are factors and forces that have been slowly eating away at the foundation and structures of this perfect edifice of authoritarian rule analogous to those dangerous termites that eat away at any wooden edifice only for one day for the entire edifice to totter and collapse.

The factors and forces are the internal dissensions, ethnic cleavages, factions jihadist guerrilla warfare that finally coalesced and magnetically lured Idriss Deby to the battlefront where he met his Waterloo on April 19, 2021.

Shedding Crocodile Tears

As far as France is concerned, Idriss Deby is definitely dispensable since there are no permanent friends in statescraft but permanent interests. This is what France has demonstrated beyond reasonable doubts in the death of Deby. That is why France came out unequivocally to defend the Army’s takeover of power after Deby’s death, throwing out the Constitution, dissolving the Parliament and setting an extended date of eighteen months for transition to civil rule again.

France defended the Chadian army’s takeover of power on Thursday after the battlefield death of President Idriss Deby presented Paris with an uncomfortable choice – back an unconstitutional military leader or risk undermining its fight against Islamists.107

While the opaque political and business ties that once bound France to its ex-colonies in Africa have frayed over the last decade, interests remain closely intertwined and under Deby’s rule Chad was a key ally in combatting Islamists in the Sahel.108 Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian justified the installation of a military council headed by Deby’s son on the grounds that stability and security were paramount at this time.109

It is not about a dilemma backing an unconstitutional military takeover of government or risking its alleged fight against Islamist jihadists. It is all about by protecting French economic and security interests in the country which have been well served under Deby’s authoritarian regime which in turn has received support from France. These so-called security interests are actually the cover for its massive business interests in the country – or put another way, its security interests are inextricably interwoven with its business interests, the latter which do not receive public attention or scrutiny.

President Emmanuel Macron has repeatedly said he wants to break from a past in which France appeared to call the shots in its former colonies, and he has urged the older generation to hand over to Africa’s younger politicians.110 This kind of statement, which has largely gone unchallenged by African intelligentsia, is an insult to Africa. France is not in any position to dictate what it wants for African countries nor is concerned African countries bound in any way to accept such an insulting suggestion.

But after a coup in Mali that saw Paris forced to accept a fait accompli and incumbent presidents in Ivory Coast and Guinea returning to power, that policy has been increasingly tested.111

Nowhere more so than in the Sahel, where France’s 5,100 troops, which includes a base in the Chadian capital N’Djamena, remain entrenched fighting groups backed by al Qaeda and Islamic State with few prospects of being able to pull out.112

France has backed Deby over the decades because he has proven himself to be a lackey of French interests. He was such a stooge because that was most probably the only way he can remain in power.

An authoritarian ruler for more than 30 years, he was nonetheless a lynchpin in France’s security strategy in Africa. Two years ago Paris came to his help dispatching warplanes to stop a Sudan-backed rebel advance. (Ibid) “France’s interpretation of the national interest dictates that they have to support a transition that keeps as much continuity as possible,” said Nathaniel Powell, Research Associate at Lancaster University and author of “France’s Wars in Chad”.113

“Mahamat’s military council is probably the best case scenario for that kind situation. The French are just hoping that military and civil discontent don’t undermine the transition too much.”114

Key in the immediate term for Paris is ensuring that the deployment of a battalion of 1,200 men to the tri-border theatre between Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger earlier this year remains in place. It is seen as vital to enable French and other forces to re-orient their military mission to central Mali and to target Islamist leaders linked to al Qaeda.115

Among the foreign leaders there was France’s President Emmanuel Macron, for whom Chad is a key ally in the fight against jihadists in region. He addressed his words to the casket, saying “you lived as a soldier, you died as a soldier with weapons in hand. “You gave your life for Chad in defence of its citizens.” He told attendees at N’Djamena packed main square, la Place de la Nation: “We will not let anybody put into question or threaten today or tomorrow Chad’s stability and territorial integrity.”116

Other visiting heads of state at Friday’s ceremony included the leaders of Guinea, Mali, Mauritania and Nigeria – who all ignored warnings from the rebels that they should not attend for security reasons. After the military honours and speeches, prayers were said at the Grand Mosque of N’Djamena. Then Mr Déby’s remains were being flown to Amdjarass, a small village next to his hometown of Berdoba, more than 1,000 km (600 miles) from the capital, near the Sudanese border.117

News of his shock death on Tuesday was met with tributes from numerous presidents – France’s Emmanuel Macron called him a “brave friend”, Cameroon’s Paul Biya said he served “tirelessly”, DR Congo’s Felix Tshisikedi called it a “a great loss for Chad and for all of Africa”, Mali’s President Bah Ndaw lamented his “brutal” death and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa called it “disturbing”.118

In mourning Déby, African neighbours extolled his commitment to peace in the subregion; Cameroon’s President Paul Biya said his death was an “immense loss for Central Africa and our continent” while Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari described the 68-year-old as “a friend of Nigeria who had enthusiastically lent his hand in our efforts to defeat the murderous Boko Haram terrorists.”119

France’s foreign minister [defended] the takeover of Chad’s government by a transitional military council.120 Jean-Yves Le Drian said during a television interview Thursday that “exceptional circumstances” made it necessary for Chad’s military to dissolve the National Assembly and form an 18-month transitional council, following the death of President Idriss Deby.121 The speaker of the National Assembly should have become president under Chad’s constitution, but speaker Haroun Kabadi issued a statement that he agreed with the council’s takeover “given the military, security and political context.”122 Le Drian said Kabadi’s position justified the military taking control.123

Gen Déby, 37, has said the army will hold democratic elections in 18 months, but opposition leaders have condemned his succession as a “coup” and an army general said many officers were opposed to the transition. A general strike has been called in protest. Fact rebels also reject it but have called a temporary ceasefire while Friday’s funeral takes place.124

Lalla Sy of BBC News provides analytical insights into the scenario unfolding in Chad: “Chad’s president was one of Africa’s longest-serving rulers and a close ally of the Western powers, especially France.The support given to president Idriss Déby – officially aimed at fighting against rebel groups and Islamist militants in West and Central Africa – consisted of intelligence for the Chadian army, aerial surveillance, and even protecting strategic points for the Chadian army. The presence of a foreign army is never well received by the local population, especially when they are soldiers of the former colonial power. The idea that France deliberately maintains a certain chaos in the region to defend its interests is believed by many. But divisions within Chad’s military – who only partially support the new leader while rebels reject him outright – raises fears of instability as a fragile transition gets underway.”125

The question has been why is Chad so important an ally to Western powers?

Déby had been a key player in security strategy in the Sahel region – and Chad is reputed for having one of the best-trained and best-equipped armies in West Africa, which is battling militants link to both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group. According to Tangi Salaun and John Irish (2021): Nestled in between Libya, Niger, Central African Republic, Sudan, Nigeria and Cameroon, Chad is a strategic outpost for France and the United States in the fight against Islamist militants across the Sahel and Boko Haram in Nigeria as well as for monitoring political instability in neighbouring countries.126

Deby has in recent years stepped into a void left by Africa’s traditional heavyweights and turned his desert nation into a powerbroker as France sought to disengage from its former colonies, most notably after a rebellion in Central African Republic in 2013.127

Highlighting his importance, in February 2019, French warplanes and drones struck Chadian rebels advancing on the capital to ensure its interests were not put at risk during a critical stage in operations against Islamist militants in the region. Sources said Paris would only intervene directly again if those interests were put in danger.128

France provided intelligence and logistical support against a new rebellion launched this month, but stopped short of direct action amid growing unease in French domestic political circles at the prospect of Deby winning re-election for a sixth time, extending his 30 years in power.128

This is where the ideological and/epistemological trap is set for the unwary international scholars, journalists and most important of all, African intelligentsia. Fighting against Islamic jihadism has been a very powerful and mesmerizing argument in the justification of imperialist involvement in Africa after the fall of Soviet communism in the early 1990s. There is probably no doubt about the clear and present dangers posed by the advancing match of Islamic jihadism in Africa in the last three decades especially after the Arab Spring.