By Alexander Ekemenah, Chief Analyst, NEXTMONEY

Introduction

Even though South China Sea has not been in the “breaking news” mode recently, the aggressive military activities by both the United States and China have not abated even after President Donald Trump exited the White House on January 20, 2021. Watchers of events in the region are, however, growing increasingly concerned about the possibility of war or major conflict being triggered off by an accident between the two superpowers through a third party.

The constellation of internal political conditions within China itself and regional hostility of geopolitical character against China by neighbouring countries, hostility in various degrees of objective concretization despite their various economic ties to China are a crucial factor that is heating up the South China Sea from the seabed, figuratively speaking. This is a powerful factor to be taken into serious consideration in the analysis of the overall scenario unfolding in the region.

While these countries have economic ties with China from one degree to another, ties that are expected to help douse the growing tension with China, they are mostly politically hostile to China. This is not only an accident of geography in which most of these countries are in close proximity with one another but also with China. Significant is the fact that most of these countries are democracies whereas China is a recognized unrepentant Communist dictatorship or hybrid authoritarianism.

Most of these countries have have one axe or the other to grind with China from one degree to another. However, in most cases, it is in the domain of maritime territorial disputes that the growing hostility with China is anchored. That is the bedrock of their hostility or antagonism towards China. Taiwan is probably the only exception in which China claims Taiwan belongs to it and, therefore, has no sovereign identity of its own. Hong Kong also falls into the same category of spurious claim of sovereignty over the two islands.

But Vietnam, Brunei, The Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, even South Korea and Japan have one dispute or another to settle with China over islands, reefs, waterways, fishing rights, and ownership of oil and gas resources surrounding the South China Sea. India is in a special category of its own. India, another juggernaut in the Indo-Pacific region, has been having overt and covert running battle with China over the years. The border clash in June 2020 was the latest in the series of age-long skirmishes with China.

The above forms part of the entire corpus of strategic thinking towards China in the last two or three decades back in Washington. Where is China really headed? Is China heading for showdown and/or war with its neighbouring countries and by extension the United States? Or are we to believe those propaganda about peaceful co-existence and cooperation with her neighbours? No one can really tell with any pin-point accuracy.

While previous US administrations have tried to hide behind the facade of diplomatic niceties in pushing their strategic interests in the Asia-Pacific region and South China Sea specifically, it was Trump administration that came out unabashedly to escalate the stakes to the stratosphere by pushing to the forefront the US national security interests as captured by the quest for freedom of open navigation operations (FONOP) in the South China Sea for the US and other South East Asian countries within the frameworks of UN Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and Sea Lanes of Communications (SLOC).

Core of Conflict in South China Sea

At the core of the territorial or geopolitical disputes and aggressive military posturings in the South China Sea from both the United States and China including neighbouring countries in the region are the estimated $3.37 trillion total trade passing through the South China Sea (2016 estimate) while 40 percent of global liquefied natural gas trade transited through the South China Sea in 2017 with 3,200 acres of new land China created in the Spratly Islands since 2013

China’s sweeping claims of sovereignty over the sea – and the sea’s estimated 11 billion barrels of untapped oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas – have antagonized competing claimants Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. As early as the 1970s, countries began to claim islands and various zones in the South China Sea, such as the Spratly Islands, which possess rich natural resources and fishing areas.1

China maintains that, under international law, foreign militaries are not able to conduct intelligence-gathering activities, such as reconnaissance flights, in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). According to the United States, claimant countries, under UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), should have freedom of navigation through EEZs in the sea and are not required to notify claimants of military activities. In July 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague issued its ruling on a claim brought against China by The Philippines under UNCLOS, ruling in favor of the Philippines on almost every count. While China is a signatory to the treaty, which established the tribunal, it refuses to accept the court’s authority.2

According to Christian Wirth (2019) [m]aritime security concerns related to shipping routes through the Malacca straits ‘chokepoint’ and the South China Sea have become the major drivers of post-Cold War international politics. Despite that the contestations in the two geographically distinct areas raise quite different legal and political questions, the issues of territorial disputes and the safety of maritime transport are intertwined, often conflated and therefore hardly separable in terms of their effects on international relations. Taken together, they are commonly seen as proof for the fact that rising China is limiting the free flow of goods at sea and, by consequence, challenging the ‘rules-based international order’. Yet, the concern with the security of the so-called Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOC) is not new. In the course of seeking to reorient their foreign and security politics after the Cold War, Japanese opinion-leaders had come to see the security of sea lanes through Southeast Asia as a ‘matter of life and death’ for their economy already in the mid-1990s. The Chinese leadership, by 2003, found itself facing this ‘Malacca Dilemma’ too. At the same time, extra-regional actors such as Australia and the US who would be among the least affected in the extreme scenario of sea lane closures, came to attach disproportionate importance to the freedom of navigation (FoN) in the ‘IndoPacific’. China’s large-scale land reclamations from 2014 onwards and an arbitration tribunal’s award for the Philippine and against the Chinese position in the South China Sea from 2016 finally brought the issue to the G-7 leaders’ and EU decision-makers’ attention, while reinforcing threat perceptions across the Asia-Pacific region.3

China sees the entire area in dispute as its sovereign territory, right or wrong, and further considers it a buffer maritime security zone to keep away foreign enemies that might have interest in laying claim of ownership or part-ownership to the zone. Hence its strong objections and counter-manouvering to the aggressive military (naval) incursion to the area especially by the United States.

While China view the South China Sea with strategic imperatives of defending China maritime zone which harbours the strategic mineral resources underneath the sea and the trade value of the sea lanes and waterways on the one hand, United States on the other hand is using the Freedom of Open Navigation Operations under the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as a cover to gain strategic access and/or bargaining power to the area in order to have its cut in the strategic oil and gas reserves in the area.

In direct relationship with the US, there are the adjacent issues of battle for technological supremacy and digital authoritarianism between the two superpowers. There is also the fear on the part of the US that China is upending the global rules-based order upon which Western powerdom currently rested and seeking to replace it with authoritarian order malleable to the dictats of China.

Who wins in this Thucydidean chess game in the South China Sea? This article seeks to unravel the disputes and lay it bare for the domino effects to become visible both in regional and global security environment and arrangement.

Culling Insights from History

Since China announced its expansive sovereignty claims in the South China Sea (SCS) in 2009, the region has become steadily militarized as Beijing seeks to legitimize and defend its claims. Other key maritime counter claimants within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), including most notably Vietnam, but also Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, have sought to modernize their naval and coast guard capabilities to preserve the status quo in the SCS. Their improvements, however, have been decidedly miniscule in comparison to Beijing’s dramatic military upgrades. Indeed, only Vietnam stands apart from its ASEAN brethren in the depth and breadth of its military modernization to offset China’s growing military footprint. Even so, Hanoi remains a very distant second to China. Taiwan—considered by Beijing to be a renegade province of China—has also been quietly upgrading its military infrastructure in the SCS. And major powers outside of the region, including Australia, France, India, Japan, the UK, and the US, are heightening their military presence in the SCS, though without installing permanent military structures to rival China’s expansion. Their activities take the form of periodic joint exercises, freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs), or both to uphold international law and rules of behaviour.4

The risk of conflict escalating from relatively minor events has increased in the South China Sea over the past two years with disputes now less open to negotiation or resolution. Originally, the disputes arose after World War II when the littoral states China and three countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, as well as Vietnam which joined later scrambled to occupy the islands there. Had the issue remained strictly a territorial one, it could have been resolved through Chinese efforts to reach out to ASEAN and forge stronger ties with the region.5

Around the 1990s, access to the sea’s oil and gas reserves as well as fishing and ocean resources began to complicate the claims. As global energy demand has risen, claimants have devised plans to exploit the sea’s hydrocarbon reserves with disputes not surprisingly ensuing, particularly between China and Vietnam. Nevertheless, these energy disputes need not result in conflict, as they have been and could continue to be managed through joint or multilateral development regimes, for which there are various precedents although none as complicated as the South China Sea.6

Now, however, the issue has gone beyond territorial claims and access to energy resources, as the South China Sea has become a focal point for U.S.—China rivalry in the Western Pacific. Since around 2010, the sea has started to become linked with wider strategic issues relating to China’s naval strategy and America’s forward presence in the area. This makes the dispute dangerous and a reason for concern, particularly as the United States has reaffirmed its interest in the Asia Pacific and strengthened security relations with the ASEAN claimants in the dispute.7

It was not President Donald Trump that first started aggressive military posturing against China nor ordered aircraft carriers to the South China Sea. The US aggressive military posturing in the region goes back many decades.

For instance when China moved aggressively towards Taiwan in 1996, former President Bill Clinton did not hesitate to send aircraft carriers to Taiwan Strait in order to counter and deter China from launching an invasion on Taiwan as it has always threatened to do. The US intervention in that brewing conflict put paid to Chinese aggressive move towards Taiwan and China has been fuming with rage since then having come to the strategic recognition that if it comes to exchange of blows over Taiwan or the entire South China Sea, China would be no match for the superior military firepower and fury that the US would unleash on China.

This strategic recognition or insight into its own military weakness or deficiency is probably what account as one of the many reasons for the progressive military modernization by China till date which has now seen China as having the accalimed largest naval forces in the world today. Contemporary China’s naval (including other branches) strength can no longer be denied even though the US naval power is completely of “deep blue sea” character and capacity which it has been flaunting at the Chinese face. US gained the mastery of the world seas after the Second World War.

While the algorithm of strength on both sides of the divide is of strategic importance, it is also undeniable that the theatre of conflict has also significantly changed to include the interplay of other dynamic factors such as the alignment or realignment of regional forces which has gone to reshape the security architecture of the area. In short, the balance of power and/or terror is more favourably disposed towards the United States than to China because of the growing hostility of host of neighbouring countries such as Vietnam and The Philippines that have also made claims of maritime rights in the South China Sea and its superjacent environment. There have been near exchange of fisticuffs over some of these claims.

Even though there is no formal military alliance among or between the South East Asian countries, with the exception of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (consisting of the US, India, Australia and Japan) there is individual hostility by these countries towards China for its aggressive posturing sometimes or oftentimes of military nature. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue has, however, not dissuaded China from aggressive moves towards its neighbouring countries.

The latest military foray into the South China Sea by the United States can be traced back to the era of Barack Obama. In other words, the US incursion into the South China Sea has been a continuum spanning four administrations uninterruptedly. Interestingly, President Joe Biden was part and parcel of the Obama administration as the Vice President then and had a seat at the table where most of the foreign policy and military strategic decisions towards China were taken. Joe Biden is back at the White House as the President and Commander-in-Chief. Therefore, his worldview, mindset and current policy thrusts and actions can be viewed from the lens of what he has contributed to the previous decisions taken towards China by Obama administration.

David Larter (2020) dislosed that [t]he Obama administration authorized two FONOPs in 2015 and three in 2016. The program has escalated under the Trump administration, with the Navy conducting six in 2017 and five in 2018. However, during Trump’s first two years in office, Navy transits of the Taiwan Strait dropped precipitously from 12 in 2016 to five in 2017, then just three in 2018. The Taiwan Strait transits picked up again in 2019, with nine transits conducted through the year.8

[But] [t]he U.S. Navy conducted more freedom of navigation operations in 2019 than in any year since the U.S. began more aggressively challenging China’s claims in the South China Sea in 2015.9 The Navy conducted nine FONOPs in the South China Sea last year [2019], according to records provided by U.S. Pacific Fleet. The FONOPs are designed to challenge China’s claim to maritime rights and dominion over several island chains in the region, which have put the U.S. and its allies at loggerheads with China.10 Patrols by U.S. warships come within 12 miles of features claimed by China, including features that the Asian nation has converted into military installations. The patrols are meant to signal that the U.S. considers the claims excessive. China views the patrols as irritating and unlawful intrusions into its waters.11

In a statement, Pacific Fleet spokesperson Lt. J.G. Rachel McMarr said the Navy was committed to continuing to demonstrate its willingness to challenge excessive claims. “U.S. forces routinely conduct freedom of navigation assertions throughout the world,” McMarr said in a statement. “All of our operations are designed to be conducted in accordance with international law and demonstrate that the United States will fly, sail, and operate wherever international law allows – regardless of the location of excessive maritime claims and regardless of current events.”12

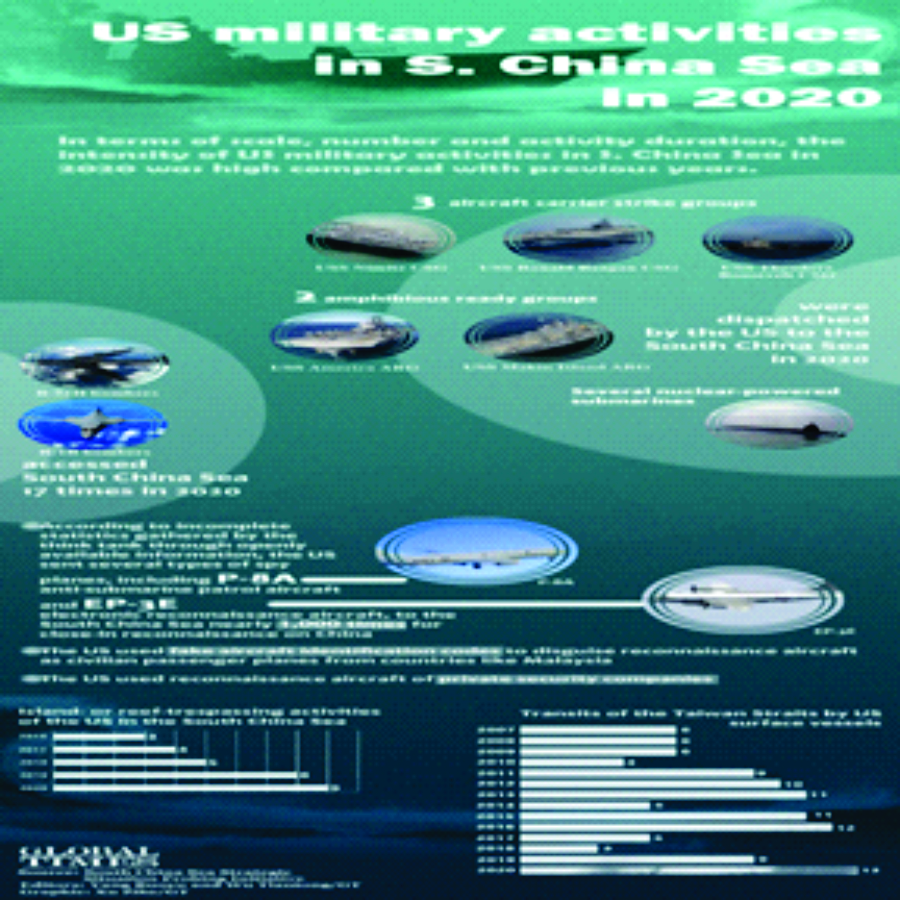

The year 2020 was perhaps the climax. And it all started in the second quarter of 2020. However, the entry of the American aircraft supercarriers into the South China Sea in July 2020, which can be considered a major turning period in the growing conflict in the South China Sea, was preceeded by smaller American warships sailing into the disputed waters of the South China Sea. In other words, there have been early signals of trouble brewing in the region.

According to a detailed report by Hannah Beech (2020) American warships have sailed into disputed waters in the South China Sea, according to military analysts, heightening a standoff in the waterway and sharpening the rivalry between the United States and China, even as much of the world is in lockdown because of the coronavirus.

The America, an amphibious assault ship, and the Bunker Hill, a guided missile cruiser, entered contested waters off Malaysia. At the same time, a Chinese government ship in the area has for days been tailing a Malaysian state oil company ship carrying out exploratory drilling. Chinese and Australian warships have also powered into nearby waters, according to the defense experts.13

Despite working to control a pandemic that spread from China earlier this year, Beijing has not reduced its activities in the South China Sea, a strategic waterway through which one-third of global shipping flows. Instead, the Chinese government’s years-long pattern of assertiveness has only intensified, military analysts said. “It’s a quite deliberate Chinese strategy to try to maximize what they perceive as being a moment of distraction and the reduced capability of the United States to pressure neighbors,” said Peter Jennings, a former Australian defense official who is the executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.14

Since January [2020], when the coronavirus epidemic began to surge, the Chinese government and Coast Guard ships, along with maritime militias, have been plying contested waters in the South China Sea, tangling with regional maritime enforcement agencies and harassing fishermen. Earlier this month [April 2020], the Vietnamese accused a Chinese patrol ship of ramming and sinking a Vietnamese fishing boat. Last month [March 2020], China opened two new research stations on artificial reefs it has built on maritime turf claimed by the Philippines and others. The reefs are also equipped with defense silos and military-grade runways.15

[T]he Chinese government announced that it had formally established two new districts in the South China Sea that include dozens of contested islets and reefs. Many are submerged bits of atoll that do not confer territorial rights, according to international law. “It seems that even as China was fighting a disease outbreak, it was also thinking in terms of its long-term strategic goals,” said Alexander Vuving, a professor at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies in Honolulu. “The Chinese want to create a new normal in the South China Sea, where they are in charge, and to do that they’ve become more and more aggressive.”16

From early July to late October 2020, US held five naval exercises within the region as authorized by former President Donald Trump. If Donald Trump has won the reelection bid in November 3, 2020 presidential election, it is arguable that the naval exercises would have most probably continued uninterrupted. And it would have also been likely that an accident could have happened leading to a larger conflict between the two superpowers – given the aggressive stance adopted by Trump administration towards China over serial disputes over the South China Sea.

What was perhaps most significant about the naval exercises during the time of Trump administration was that they took place during the rage of coronavirus pandemic that earlier broke out in late December 2019. Indeed, the naval exercises have nothing to do whatsoever with the virulent disagreements over the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. The US did not go to the South China Sea under the pretext of the coronavirus pandemic. At least there is no evidence to this effect. Both are parallel when it was largely expected that the two countries should have cooperated to stem the tidal wave of the raging pandemic. While the US failed to exercise global leadership to roll back the encroachment of the pandemic, US was seen at the same time conducting gunboat diplomacy to South China Sea in an apparent hegemonic struggle with China for strategic dominance or supremacy in the South China Sea.

While the number of aircraft supercarriers are known alongside their capacities, details of other military hardwares and softwares, for instance, the number of combat aircrafts, submarines and their types and capacities, warships and their various capacities and cyber platforms are not publicly known ostensibly for national security reasons. However, it is now known through some media reports and the South China Sea Situation Probing Initiative (SCSPI) that B-52H Stratofortress long range strategic bomber (a nuclear delivery aircraft), B-1B Lancer long range strategic bomber (another nuclear delivery aircraft), F-35 Lightning II Stealth combat aircrafts, F-18A Hornet combat aircrafts, several reconnaisance planes including AWACS plane participated in the naval drills in 2020.

Tony Walker (2020) an Adjunct Professor at Schools of Communications, La Trobe University, Australia, said [t]he deployment of three US nuclear-powered aircraft carriers to the South China Sea have further tested [and] strained relations between China and the United States.17 The US naval exercises represent an enormous aggregation of firepower. Adding to tensions, the US deployment coincides with Chinese war games in the same vicinity. These waters are becoming congested naval space.18 This is the first time since 2017 that America has deployed three carrier battle groups into contested waters of the South China Sea and its environs. You would have to go back a further ten years for another such display of raw American naval power in the Asia-Pacific.19

In 2017, the US sent a three-carrier force into the region to exert pressure on nuclear-armed North Korea to cease provocative missile tests and the further development of its nuclear capability.20 On this occasion, it is China that is being reminded of American capacity to assert itself in what has become known as the Indo-Pacific. This describes a vast swathe that laps at China’s borders from India in the west to Japan in the north-east.21 Washington seems bent on conveying a message. However, it is not clear that China is in a mood to heed such messages in an atmosphere of escalating rhetoric.22

Under Trump Administration, the year 2018 might be considered significant not just for the number of naval exercises conducted in the South China Sea but in the number of Western allies participating in these exercises. It was the year Trump Administration released the Indo-Pacific (Maritime) Strategy. The multilateral character of the naval exercises is clearly indisputable given the number of countries that participated in them in this year. According to Ralph Jennings (2018), a surge in naval maneuvers in the South China Sea by Western allies this year is keeping China from any further expansion into the contested waters, analysts say.23 Vessels from Australia, France, Japan and the United States have sent ships to the 3.5 million-square-kilometer sea in 2018. They believe the sea rich in fisheries and fossil fuel reserves to be an international waterway, but China claims about 90 percent of it and has militarized several key islets.24

Jennings further revealed in his report that “The foreign military exercises, naval ship passages and ports of call, along with one U.S. B-52 flyby have effectively stopped China from pushing ahead with expansion that’s also opposed by five other maritime claimants in Asia, experts believe. “You take a realist perspective of power, and it’s a way of ensuring the South China Sea is permanently contested,” said Alan Chong, Associate Professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. “So, the Chinese will issue angry statements and so on, warning of consequences, but the fact that all these multinational navies keep doing it in spite of Chinese warnings, it defies Beijing,” he said.25

The number of hours that navy ships have spent in the South China Sea has hit a high this year, said Carl Thayer, Asia-specialized Emeritus Professor at the University of New South Wales in Australia. The U.S. Navy has sailed naval vessels into the South China Sea eight times over the past 18 months and flew two B-52 bombers over it last month [June 2018]. This month [July 2018] the United States and the Philippines kicked off their own joint naval exercises to train Manila’s navy. Australia passed three ships though the sea in April en route to a goodwill visit to Vietnam, and Japan anticipates sending an Izumo-class helicopter carrier through the sea again this year as it did in 2017. Last year military officers from the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations bloc boarded the Izumo. France passed a frigate and an assault ship through near Chinese-held islets in May [2018].26

Reports in May [2018] of Chinese missiles deployed to the sea’s Spratly Islands galvanized much for the foreign naval attention this year, Thayer said. [T]he U.S. Navy wrapped up its biennial RIMPAC exercises, which are based out of Honolulu. The series of live-fire drills and scenario-based exercises brought together 25,000 people from 25 countries including South China Sea claimant states such as Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. The Philippines gained from RIMPAC by “becoming comfortable” with allies and learning to “operate smoothly with them,” said Jay Batongbacal, a University of the Philippines international maritime affairs Professor. All four Southeast Asian countries contest some of the waters that China calls its own. The United States dis-invited Beijing from RIMPAC this year.27

China criticizes these movements and often responds with its own. It cites historical records to back its claim to most of the sea. Chinese vessels followed their Australian and French counterparts. Its navy sent an auxiliary general intelligence ship this month to track the RIMPAC exercises near Honolulu, according to American media reports quoting a Pacific Fleet spokesman. In April, China held military drills for two days in the sea. They brought together about 10,000 personnel and 48 naval vessels.28

China wants to keep the others away, said Jonathan Spangler, director of the South China Sea Think Tank in Taipei. “There’s the demonstrating that you are a world leader politically and militarily, the power projection thing, and there’s the deterrent aspect,” Spangler said. “There’s also the sort of insurance policy aspect. In the off-chance there’s a conflict, then (China) will be prepared.”29

But use of the sea by Western navies effectively keeps China from building up more islets – many of which it has landfilled since 2010 – or testing the patience of the Southeast Asian maritime claimants, experts say. China “cannot assume on a role and can take the South China Sea by stealth” as they build economic ties to get on the good side of other claimants, Chong said. Too much pushback against other navies would scuttle Chinese statements that it’s a good neighbor in Asia, he added. Western-allied ship movement now follows a Cold War pattern where American and Soviet ships tested each other’s influence, Thayer said. U.S. and Soviet vessels had faced off, for example, in the Indian Ocean.30

China may have called off plans to build on Scarborough Shoal, which is contested by Beijing and Manila, as former U.S. President Barack Obama sent ships, he said. A U.S. carrier strike group reached the sea in 2015. “Both sides are contributing to the tensions in the sense that anything America does China will push back,” he said. “Several years ago, the expression was you do 1 we do 1.5 times, you do two, we do 2.5.”31

In early July 2020, in the midst of global raging and panic over the outbreak of coronavirus pandemic, the US launched an aggressive naval exercise into the South China Sea. Trump administration sent two nuclear-powered aircraft supercarriers (USS Nimitz and USS Ronald Reagan) to the area which was later joined by another supercarrier (USS Theodore Roosevelt) all commanding hitherto uncommon naval firepower. Interestingly, USS Theodore Roosevelt contracted the coronavirus pandemic in which one of its sailor died in late March/early April 2020 and the supercarrier has to dock at the home port for detoxification after which it returned to active duties in early June 2020. Naturally, the gunboat exercises drew the ire of the Chinese who accused the US of trying to destabilize the region.

The U.S. and Chinese navies are holding competing naval exercises in the South China Sea, as the Beijing accuses Washington of militarizing the region. [T]he U.S. Navy’s Reagan and Nimitz carrier strike groups transited from the Philippine Sea to the South China Sea and held the first dual-carrier drills there since 2014.32

USS Nimitz (CVN-68) and its strike group have been involved in near-constant dual-carrier stike group operations since June 21, first with the Theodore Roosevelt CSG and then the Reagan CSG. USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) operated with Nimitz in the Philippine Sea. The exercises follow a lull in U.S. carrier operations in the Western Pacific while Theodore Roosevelt was sidelined in Guam dealing with a COVID-19 outbreak.33

After Nimitz and its escorts took a quick break in Guam, Japan-based USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76) and its strike group joined for a lengthier round of dual-carrier, or carrier strike force, operations that have spanned first the Philippine Sea and now the South China Sea. “The Nimitz Carrier Strike Force celebrated Independence Day with unmatched sea power while deployed to the South China Sea conducting dual-carrier operations and exercises in support of a free and open Indo-Pacific,” reads a Saturday statement from the Navy.34

Beijing conducted parallel drills off of the Paracel Islands in contested waters. “The military exercises are the latest in a long string of [People’s Republic of China] actions to assert unlawful maritime claims and disadvantage its Southeast Asian neighbors in the South China Sea,” reads a statement from the Defense Department. “The PRC’s actions stand in contrast to its pledge to not militarize the South China Sea and the United States’ vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific region, in which all nations, large and small, are secure in their sovereignty, free from coercion, and able to pursue economic growth consistent with accepted international rules and norms.”35

The Pentagon said the Chinese exercises are a departure from the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea in which China and other nations with overlapping claims agreed to curtail military exercises in the region.36

In a press conference, Chinese officials pushed back against the assertion that their exercises violated any agreement and reaffirmed their territorial claims in and around the islands off the coast of Vietnam. “I want to stress once again that the Xisha Islands are indisputably China’s territory. China’s military training in the waters surrounding the Xisha Islands is within China’s sovereignty and beyond reproach,” Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Zhao Lijian said, using the Chinese term for the Paracel Islands. “At present, thanks to the joint efforts by China and ASEAN countries, the situation in the South China Sea is generally stable and witnessing sound development. Under such circumstances, it is completely out of ulterior motives that the U.S. flexes its muscles by purposely sending powerful military force to the relevant waters for large-scale exercises. The U.S. intends to drive a wedge between regional countries, promote militarization of the South China Sea and undermine peace and stability in the region. The international community, especially the regional countries, have seen this very clearly.”37

According to press reports, Chinese ships were operating near the U.S. carrier formations. “They have seen us, and we have seen them,” Nimitz Carrier Strike Group commander Rear Admiral James Kirk told Reuters. “We have the expectation that we will always have interactions that are professional and safe. … We are operating in some pretty congested waters, lots of maritime traffic of all sorts.”38

“Two US aircraft carriers conducted exercises in the disputed South China Sea on Saturday with China also carrying out manoeuvres that have been criticised by the Pentagon and neighbouring states.”39 The USS Nimitz and USS Ronald Reagan performed operations and exercises in the South China Sea “to support a free and open Indo-Pacific”, a US Navy statement said.40 It did not say exactly where the exercises were being conducted in the South China Sea, which extends for 1,500 km (900 miles) and 90 percent of which is claimed by China despite the protests of its neighbours. “The purpose is to show an unambiguous signal to our partners and allies that we are committed to regional security and stability,” Rear Admiral George M Wikoff was quoted as saying by the Wall Street Journal, which first reported the exercises.41 China and the United States have accused each other of stoking tension in the strategic waterway at a time of strained relations over everything from coronavirus to trade to Hong Kong.42

Interestingly, if there is any area where Joe Biden and Donald Trump have intersectional agreement or concurrence of view and action thrust, despite the virulent disagreement over many issues and the bad name that Donald Trump finally earned for himself as the most cantakerous US President ever, it is China. This is precisely where Joe Biden has hardened his tone and position and does not look willing to moderate this hardened stance.

While Donald Trump was defeated in the November 3, 2020 presidential election in a landslide electoral victory that has not been witnessed in US political history, the expectation was that the new administration would completely overturn the entire policy legacy left behind by Trump administration especially in the foreign policy arena and strategic military domain in what would have been a justified policy discontinuity given the acrimonies and antagonisms that accompanied the 2020 presidential election. But interestingly, it was precisely in the foreign policy firmament and military domain that we see a concurrence of views between the previous and the new administration.

In the core of the US political class (cutting across both parties) there have been grave concerns whether there would a continuity or reversal of foreign policy objectives and priorities under Trump administration by the new Biden administration.

In an international security environment described as one of renewed great power competition, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS formed an element of the Trump Administration’s confrontational overall approach toward China and its efforts for promoting its construct for the Indo-Pacific region, called the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP).43

China’s actions in the SCS in recent years – including extensive island-building and base-construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, as well as actions by its maritime forces to assert China’s claims against competing claims by regional neighbors such as the Philippines and Vietnam – have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China’s maritime forces at the Japan-administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. Chinese domination of China’s near-seas region – meaning the SCS and ECS, along with the Yellow Sea – could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere.44

Potential general U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. security relationships with treaty allies and partner states; maintaining a regional balance of power favorable to the United States and its allies and partners; defending the principle of peaceful resolution of disputes and resisting the emergence of an alternative “might-makes-right” approach to international affairs; defending the principle of freedom of the seas, also sometimes called freedom of navigation; preventing China from becoming a regional hegemon in East Asia; and pursing these goals as part of a larger U.S. strategy for competing strategically and managing relations with China.45

Potential specific U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: dissuading China from carrying out additional base-construction activities in the SCS, moving additional military personnel, equipment, and supplies to bases at sites that it occupies in the SCS, initiating island-building or base-construction activities at Scarborough Shoal in the SCS, declaring straight baselines around land features it claims in the SCS, or declaring an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the SCS; and encouraging China to reduce or end operations by its maritime forces at the Senkaku Islands in the ECS, halt actions intended to put pressure against Philippine-occupied sites in the Spratly Islands, provide greater access by Philippine fisherman to waters surrounding Scarborough Shoal or in the Spratly Islands, adopt the U.S./Western definition regarding freedom of the seas, and accept and abide by the July 2016 tribunal award in the SCS arbitration case involving the Philippines and China.46

The issue for Congress is whether and how the Biden Administration’s strategy for competing strategically with China in the SCS and ECS will differ from the Trump Administration’s strategy, whether the Biden Administration’s strategy is appropriate and correctly resourced, and whether Congress should approve, reject, or modify the strategy, the level of resources for implementing it, or both.47

But it is precisely on China that served as a meeting ground by both the previous Trump Administration and the new Biden Administration.

While [t]he new Biden administration has been reversing many of the Trump administration’s policies in areas such as immigration and energy, but when it comes to confronting China’s actions in the South China Sea, at the highest levels of power the song remains the same.48

In its opening weeks, the Biden administration has signaled it will continue many of the Trump administration’s hardline policies towards China. And it has not backed off heavy naval presence in the Indo-Pacific region, after a U.S. ship conducted “freedom of navigation operation” (FONOP) earlier this month. Then Feb. 9 the Navy announced that two carriers were operating together in the hotly disputed South China Sea.49

The destroyer John S. McCain transited the Taiwan Strait Feb. 4, which China denounced as a provocation, and the following day the McCain performed a FONOP challenging competing claims in the disputed Paracel Islands, a patrol that was accompanied by what experts noted was an extraordinarily detailed explanation.50 On Feb. 9, China’s Foreign Ministry slammed the Navy’s two-carrier exercise in the South China Sea, saying it was “not conducive to peace and stability in the region,” and that China would “work together with regional countries to safeguard peace and stability in the South China Sea.”51

Just 21 days into Biden’s presidency, and with a remarkably small sample size, the emerging policy on China looks nearly indistinguishable from the Trump policy, which has led many China watchers to believe that a policy of strategic competition with Beijing — in the maritime realm and beyond — is here for the long term. Or at least for Biden’s.52

Despite radically different positions on a range of national security issues, when it comes to the China relationship, Presidents Joe Biden and Donald Trump have charted similar courses thus far.53 Both Biden and new Secretary of State Antony Blinken have signaled the need for some cooperation, particularly on tackling climate change. But the Biden administration has also held the line on the 2020 decision by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to formally reject China’s expansive claims in the South China Sea and has backed Pompeo’s late-hour determination that China’s actions against Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang province constituted genocide.54

During calls with counterparts in Vietnam and the Philippines, new Secretary of State Antony Blinken made clear the U.S. was not backing off its rejection of excessive Chinese claims of maritime rights and that the U.S. was committed to maintaining a rules-based order in the South China Sea.55 In a State Department readout of a Jan. 27 call between Blinken and Philippines Secretary of Foreign Affairs Teodoro Locsin, Blinken said the United States rejected China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea “to the extent they exceed the maritime zones that China is permitted to claim under international law as reflected in the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention,” according to a statement from State spokesman Ned Price.56 “Secretary Blinken pledged to stand with Southeast Asian claimants in the face of PRC pressure,” the statement reads.57

It also made clear the U.S. would defend against attacks on Philippines military or government assets. “Secretary Blinken stressed the importance of the Mutual Defense Treaty for the security of both nations, and its clear application to armed attacks against the Philippine armed forces, public vessels, or aircraft in the Pacific, which includes the South China Sea,” the statement reads.58

The direct language and restating of U.S. policy so early in the Biden White House was a deliberate signal that there has been no significant shift in policy with the new team, said Bonnie Glaser, who leads the China Power Project at Center for Strategic and International Studies. “It is essentially a restatement of Trump policy, articulated by Pompeo in mid-2018 and mid-2020,” Glaser said. “It reaffirms that the Mutual Defense Treaty applies to the South China Sea and that the U.S. opposes Chinese maritime claims that are inconsistent with UNCLOS. …The fact that U.S. policy was stated very clearly within the first week of the Biden administration demonstrates U.S. commitment to alliances and U.S. willingness to push back against Chinese actions in the South China Sea that undermine the interests of the U.S. and its allies and partners.”59

What is further interesting about the new posturing from Biden administration is the review of the China’s strategy that is already being carried out at the Pentagon and the acompanying geostrategic elements of thinking that further up the game.

On Feb. 4, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin launched a force-wide posture review to address if the military has the right capabilities in the right places to address the threats the country faces. And in comments Feb. 10 at the Pentagon, Biden said Austin had ordered a China task force to ensure the DoD is pursuing the right concepts and technologies. “Today I was briefed on a new DoD-wide China task force that Secretary Austin is standing up to look at our strategy, operational concepts technology and force posture and so much more,” Biden said. He added that the task force would map out the course that would incorporate allies and partners and a whole-of-government approach to meet the China challenge.60

There have been some clues as to what the administration is thinking coming in the door. In response to a question about the Trump administration’s late-hour force structure assessment, new Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks said she was inclined to support many, but not all, of the themes in the assessment. “There’s some really interesting operational themes that I’m attracted to,” Hicks said. “There’s a focus on increasing use of autonomy. There’s a focus on dispersal of forces and there’s a focus on growing the number of small surface combatants relative to today.”61

Hicks’ discussion of “dispersal of forces” is seemingly a reference to the Navy’s plans to fight in a more spread-out manner, using sensors on unmanned autonomous platforms linked to manned platforms to push capabilities to more places for less money than it would cost to spread those sensors around on manned platforms.62 That likely means the Navy’s networking effort, Project Overmatch, upon which the whole concept depends will go forward. By extension, the broader Air Force-led Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control network will likely be a priority as well.63

She also pointed to increasing investments in small surface combatants, which is another means of starting to reduce the cost of spreading around significant capabilities for less money.64 The next-generation Constellation-class Frigate was awarded last April to Fincantieri and its Wisconsin shipyard Marinette Marine.65 It is unclear if hypersonic missiles, a key Trump-era priority aimed at giving the military the ability to rapidly strike Chinese targets at extremely long ranges, will endure as a priority in the Biden administration.66

In the highest-level to date interaction between the U.S. and China since the new administration took office, Blinken released a statement saying the U.S. was not backing down on China’s destabilizing role in the region. “Secretary Blinken stressed the United States will continue to stand up for human rights and democratic values, including in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong, and pressed China to join the international community in condemning the military coup in Burma,” Price’s statement read.67

For its part, China released a statement saying it wanted the U.S. to “uphold the spirit of no conflict, no confrontation, mutual respect and win-win cooperation, focus on cooperation and manage differences, so as to push forward the healthy and stable development of bilateral relations.”68

Seth Cropsey, a Reagan and George H.W. Bush-era DoD official who is now a senior fellow at the conservative Hudson Institute, said that so far Biden’s policies have been encouraging. “They are a little tougher than what I thought I was going to see,” Cropsey said. “For example, I don’t think that any of Taiwan’s representatives to Washington had been invited to attend the inauguration and Biden did that. They have said that they’re going to continue to arm sales to Taiwan … and we don’t know what that means but it’s a positive thing to say.”69

Cropsey said holding off on high-level engagements with China until consulting with allies in the region was a smart move, and he was impressed with Blinken’s upholding of Pompeo’s determination that China was committing genocide against the Uighur population in Xinjiang and the continuation of naval activity in the South China Sea. “Look, it’s impossible to tell where this is going to lead and whether it is the keel of the Biden administration policy, but it looks encouraging so far.”70

The growing confrontation in the South China Sea and in the Asia-Pacific in general is not only of political but also of military strategic significance. It is both a test of political will or resolve and demonstration of military kinetic and non-kinetic powers. Both superpowers have been breast-feeding each for decades. But this era of cooperation has probably drawn to a clangorous close. Both superpowers can now be said be in an era of cooperation within the fulcrum of competition i.e. cooperation-competition management nexus. They are now shaking their fists at each other’s face but without hitting at each other. The hitherto political understanding or tolerance that underpines their decades-long relationship has been exhausted and has ended in a cul-de-sac. The global political environment underpined by liberalism has emasculated the ability of the last strongholds of hybrid dictatorship (such as China) to exercise authoritarian control over the global order.

On the military strategic domain, the increasing modernization of the China’s PLA and the advent of new technologies especially on the part of the United States, for instance, the advent of 5th-generation fighter planes and maritime dominance by nuclear-powered aircraft supercarriers, submarines and sophisticated warships such as the stealthy USS Zumwalt, have changed the military equations between the two superpowers. This has inevitably spilled over to the Asia-Pacific region where the countries there have gained access to some of these advanced military hardwares and therefore helping to tilt the balance of power in the region. While China can bully some of the smaller South East Asian countries, it cannot do so in the case of India, South Korea and Japan with their widely acknowledged military firepower within global ranking order. India, South Korea and Japan are within the ten topmost powerful military bracket in the world. While Taiwan is mostly under-rated, it has sat quitely like a fortress for the past seventy years right under the very nose of China – less than 200 kilometers away from the mainland.

What China is saying

It would be apposite to have a bird’s eyes view of the unfolding scenario of disputes in the South China Sea (within a period of four months) that have been pitting the two superpowers against each other in recent times.

May 8, 2020: China announces a unilateral fishing ban from May 1 to Aug. 16 in the South China Sea (SCS), drawing criticism from Vietnam.

May 12, 2020: A Chinese survey ship and two coast guard vessels in the SCS leave the disputed waters after an oil exploration vessel contracted by Malaysian state energy company Petronas left the disputed waters earlier the same day.

May 28, 2020: Indonesia submits a diplomatic note to United Nations Secretary-General reiterating the validity of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and endorsing the 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration on the South China Sea.

June 4, 2020: Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen publicly denies claims that China has set up a military presence in the Ream Naval Base.

June 10, 2020: Chinese President Xi Jinping exchanges congratulatory messages with Philippine counterpart Rodrigo Duterte to celebrate the 45th anniversary of bilateral diplomatic ties. Xi says China is ready to promote closer political, economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties to new levels.

June 10, 2020: Philippine Defense Minister Delfin Lorenzana arrives on Thitu Island to launch a beaching ramp for construction of infrastructure on the disputed island reef in the SCS.

June 13, 2020: Vietnam protests the laying of undersea cables at the disputed Paracel Islands by China, citing the activity as a violation of Vietnam’s territorial sovereignty and a potential source of concern for militarizing the disputed islands in the South China Sea.

July 1, 2020: Chinese Premier Li Keqiang exchanges congratulatory messages with Thai counterpart Prayut Chan-o-cha on the 45th anniversary of bilateral diplomatic ties. The two leaders reaffirm the importance of Sino-Thai strategic partnership and of collaboration in containing COVID-19.

July 13, 2020: Trade and commerce officials from China and Myanmar hold an online planning meeting to discuss cross-border electronic commerce between China’s Yunnan province and Myanmar’s Mandalay region. The two sides emphasize the increasing importance of digital and mobile platforms for payments and retail trade in furthering bilateral business, economic, and trade ties.

Aug. 6, 2020: Vietnam lodges protests against China’s recent military drills near the Parcel and Spratly Islands in the South China Sea.

Aug. 8, 2020: ASEAN foreign ministers reiterate their call on all countries to refrain from the use of force and exercise self-restraint in the South China Sea.

Aug. 10, 2020: Myanmar’s government formally approves China’s strategic deep seaport project in the Rakhine State. The project is part of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor and China’s Belt and Road Initiative and will, when complete, provide China with direct access to the Indian Ocean and allow it to bypass the Malacca Strait for oil and other imports.

Aug. 20, 2020: Yang Jiechi, member of China’s Politburo and director of the Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Affairs Office, arrives in Singapore for a three-day visit and meets Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. The two leaders discuss bilateral cooperation and the COVID-19 situation, as well as regional security and global developments. The two countries are keen to strengthen supply chain and cross-border connectivity to facilitate economic recovery amidst the global pandemic.

Aug. 24, 2020: The third Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Leaders’ Meeting convenes via videoconference. Chinese Premier Li co-chairs the meeting with Laotian counterpart Thongloun Sisoulith. At the meeting, China pledges to share water management data on the Mekong River, which would enable downstream countries to make plans and adjustments in the river’s flow for fishing and farming practices.

Aug. 26, 2020: Philippines’ Foreign Minister Teodoro Locsin indicates in a public interview that Manila will continue to patrol the Spratlys, ignoring warnings from China to stop “illegal provocations” in the disputed island chain.

Aug. 27, 2020: Regional trade ministers indicate that they are making significant progress to finalize the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a sprawling trade agreement that spans 15 countries in the Asia-Pacific, including China and all 10-member states in ASEAN. The ministers are hopeful that the deal will be ready for signing at the summit of RCEP leaders in November.71

China, [however], criticized joint naval exercises conducted by two U.S. Navy aircraft carrier groups in the South China Sea on July 4, accusing the U.S of undermining stability in the region.72 In a daily briefing, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said that the exercises were performed “totally out of ulterior motives,” adding that the U.S. “deliberately dispatched massive forces…to flex its military muscle,” the Associated Press reported.73

The U.S. Navy had said that its nuclear-powered aircraft carriers USS Nimitz and USS Ronald Reagan along with their supporting vessels and aircraft had conducted exercises “designed to maximize air defense capabilities, and extend the reach of long-range precision maritime strikes from carrier-based aircraft in a rapidly evolving area of operations.”74

China had begun conducting its own naval exercises in the sea on July 1, around the Paracel Islands, which it had seized from Vietnam in 1974. Tensions between the two countries have risen in the past months over trade, the coronavirus pandemic and China’s crackdown on Hong Kong.75

Through the exercises, the U.S. aims to send a message to Beijing that “it’s not backing down, and that it’s still able to do this,” Gregory Poling of the Center for Strategic and International Studies told CNBC, referring to the U.S. aim to demonstrate that its ability to project force in the region hasn’t been hurt by coronavirus outbreaks in the Navy.76

China claims about 90% of the South China Sea, through which about $3 trillion of trade passes each year. In 2016, an international tribunal in The Hague rejected China’s claims of sovereignty over the waters in a case brought by the Philippines. While this decision was legally binding, China has refused to abide by it as there has been no mechanism to enforce it. Other countries like Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, Taiwan and Vietnam have also challenged China’s assertion on the region. To push back against China’s unilateral seizure of the reefs and construction of military installations on the sea, the U.S. has in, recent years, increased what it refers to as freedom of navigation operations, in which its naval vessels sail near Chinese-held islands and other disputed territory in the sea. In the midst of the pandemic, China has moved to project its military and political power in its neighborhood. In the past few weeks, China has engaged in clashes with the Indian military along their disputed border, with Malaysian and Vietnamese vessels in the South China Sea, and twice sailed an aircraft carrier through the Taiwan Strait. Beijing has also unilaterally moved to seize new powers over Hong Kong. The U.S. Navy has sought to show that its operational capabilities haven’t been hurt by the coronavirus pandemic. Last month [June 2020], the navy operated three carrier strike groups in the Pacific, for the first time since 2017.77

Two JH-7 fighter bombers attached to an aviation brigade of the air force under the PLA Southern Theater Command taxi in close formation before takeoff during an assault flight training exercise on July 21, 2020. Photo: chinamil.com.cn

The United States intensified its military activity in the South China Sea last year, raising the risk of a confrontation with China in the strategically important waters, according to a Beijing-based think tank. The US conducted eight so-called freedom of navigation operations in the year – three more than in 2018 – during which its vessels sailed within 12 nautical miles of land claimed or occupied by China, according to the South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative’s annual report. American forces also engaged in at least 50 joint and multiple exercises with countries from Southeast Asia and elsewhere in the region, it said.78

South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative (SCSPI) affiliated to Peking University is a new Chinese strategic think tank monitoring the military activities particularly of the United States in the South China Sea in particular and Asia-Pacific in general.

SCSPI is an open think tank and cooperative network of Chinese and foreign scholars aimed at comprehensively and objectively grasping the dynamics and news in the South China Sea by accurately probing the military, political, economic and environmental situation there. For the purpose of research, it has established its own system of monitoring maritime and aerial situation and is continuously tracking and releasing aircraft and vessel movements from countries within and outside of the region.79

At 2:22 pm on Saturday, [August 1, 2020] China’s Army Day, think tank South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative (SCSPI) released the latest movement of US warships on its Weibo account, including the USS Ronald Reagan aircraft carrier and USS America amphibious assault ship in the East China Sea.80 From July 15 to 30, SCSPI’s Weibo account has released a total of 24 updates on the activity tracks of US warships and warplanes in regions including South China Sea and East China Sea. This has attracted wide domestic and foreign attention.81

In an exclusive interview with the Global Times reporters Liu Xuanzun and Guo Yuandan, Hu Bo, director of SCSPI, introduced why the SCSPI platform releases the information to the public, and the characteristics of US military activities in the South China Sea.82

Speaking on the original intention of releasing US military activities in the South China Sea, Hu said that, “We do not want to create big news. We just want to objectively present the data and often we take no position.” “We mainly want to help experts who conduct research on the South China Sea, as well as the general public, to build a general knowledge, because, apart from militaries of China, US and some other countries, only very few people know what is really going on in the South China Sea that has been frequently appearing on media reports. This even includes most researchers,” Hu said, noting that “When people have a general knowledge, their view and research on the South China Sea could become more rational, which should contribute to peace from a long run.”83

Hu said an imbalance exists in terms of information disclosure in the South China Sea, as the US releases a lot more information, so the outside world only sees a South China Sea situation shaped by the US officials and think tanks. “Our information releases caught so much attention and this is another indication of the lack of South China Sea information,” Hu said.84

According to data released by SCSPI, in July, the US military conducted 67 reconnaissance sorties in the South China Sea with large reconnaissance aircraft, ranging from multiple types of warplanes including P-8A and P-3C anti-submarine patrol aircraft. “Even so, what we have been able to monitor and release was only a tip of the iceberg,” Hu said.85

Source: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1218193.shtml

SCSPI uses Automatic identification system (AIS) and Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) to track vessels and aircraft. Information in these two systems is open source commercial data, and accessible via multiple routes in China and abroad. “Our job is data mining. From the vast original data, we have set relevant parameters, so we can automatically gather data related to the South China Sea strategic situation, like those on warships, warplanes, public service vessels and fishing boats, and make statistics and analyses based on that,” Hu said.86

Since the data sources and approaches are relatively simple, the data’s accuracy, completeness and stability cannot match official data from internal systems of related countries, he said. “For instance, we can only track parts of trails by large reconnaissance aircraft, but not small ones. Neither can we track activities by aircraft carrier-based warplanes. And if warplanes do not open ADS-B transponder, we will be unable to track them.”87

According to tracking data, the types of US aircraft that have appeared in the South China Sea have reached a rare level compared to other regions in the globe, as the E-8C battlefield command and surveillance aircraft and E-3B early warning aircraft are frequently appearing above waters near China, Hu said.88

On the other hand, with China’s capabilities rapidly rising in the recent years, particularly its Navy and Air Force, the encounters between China and US military forces are becoming more frequent. Every day there are several encounters and thousands of them each year. Most of them are handled professionally and safely and only a small amount of them are risky, according to Hu.89

Hu said that there are mainly three kinds of risks. While the Chinese and US militaries have a series of codes including Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea to avoid risks, these rules are set up for literally unplanned encounters.90

In reality, many encounters are intentional: First, US warships frequently trespass into waters within 12 nautical miles of islands and reefs of China’s Nansha Islands or territorial waters and inland waters of Xisha Islands, and China has to expel and intercept them, in which no guarantee could be made that no accident will occur during confrontation.91

Second, US warplanes’ frequent aerial close-up reconnaissance operations are also very risky, and China is also expected to conduct correspondent measures including raising alert. The (Hainan Island) collision incident in 2001 is a direct result of US close-up reconnaissance.92

Third, both China and the US conduct all kinds of military training and exercises every year, and both sides usually would conduct reconnaissance and monitoring on each other. This is understandable on a military perspective, but frictions are bound to occur if distance is not well kept. In December 2013, when China’s Liaoning aircraft carrier task group was training in the South China Sea, USS Cowpens cruiser sailed abnormally close and crossed into the Chinese flotilla, and a Chinese landing ship was left with no choice but to force the US ship to a stop. The closest distance was only 50 meters.93

In recent years, the US has been paying increasingly less attention to safe distance, and a crisis would very easily take place, according to Hu. “Given the current overall relations between China and the US, if any maritime or aerial accident takes place, the friction could likely not be effectively managed and result in an escalation. Therefore, the uncertain factors in Chinese and US militaries’ interactions in the South China Sea are large, and the risks are becoming higher,” Hu said.94

SCSPI’s tracking data show that the US military has significantly increased large reconnaissance aircraft activities in July compared to May’s 35 and June’s 49. July’s figure 67 is almost twice as many as May’s.95

Reports show that since 2009, the US military has significantly enhanced the frequency of activities in the region by boosting the presence of surface vessels by more than 60 percent, reaching about 1,000 ship-days a year. In the air, it sends on average three to five warplanes to the South China Sea a day, most of them being reconnaissance aircraft, making a total of more than 1,500 sorties a year, almost twice as many as in 2009.96

In addition to this, US military activities have also become more pointed to China. US reconnaissance aircraft made intensive flights when the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was conducting operations. During the PLA’s drills in the Xisha Islands from July 1 to 5, the US conducted 15 reconnaissance aircraft operations in these five days. In July, US reconnaissance aircraft entered areas within 70 nautical miles of China’s territorial sea baseline nine times, six times within 60 nautical miles, and in the closest event, only about 40 nautical miles away from China’s territorial sea baseline.97

These kinds of close-up reconnaissance are obviously provocations, as “since the US military has all-round, advanced reconnaissance technologies, such a high frequency aerial reconnaissance and close distance would not be necessary if it just wants to gather intelligence on China,” Hu said.98

Hu said “the reason behind the significantly increased US aerial reconnaissance in 2020 could be related to the COVID-19 outbreak. Since many US warships suffered from group infection events which resulted in a lack of warships, the US might have opted to enhance aviation reconnaissance.”99

Hu pointed out that out of the strategic thinking of great power competition, the US is applying prejudice and judging others. It worries about China’s presence in the South China Sea during the pandemic, so it increased military deployment. “US military deployments and activities in the South China Sea took 60 percent of its forward deployed forces troops in the Indo-Pacific region,” Hu noted.100

Pride of the Chinese armadA: The first Chinese aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, was originally a Soviet model built in 1986. In 1998, the stripped hulk was sold to China by Ukraine and rebuilt by the Dailian Shipbuilding Industry Company in northeastern China. It was completed in 2012 and has been ready for service since 2016. Source: https://www.dw.com/en/philippines-asks-chinese-flotilla-to-leave-disputed-reef/a-56943127

According to Zhang Zhihao (2019) reporting for China Daily: China will likely face more disputes when pushing for progress in negotiations and cooperation regarding the South China Sea, according to new situation report released on Tuesday.101 The report suggests China should enhance maritime strategic dialogue with the United States, closely monitor subtle moves by some ASEAN countries and persuade extra-regional powers such as Japan, Australia and the United Kingdom to help ease tensions in the region.102

The South China Sea Situation Report was published by the South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative, a think tank under Peking University’s Institute of Ocean Research. The initiative was launched on Tuesday to provide data services and situation analysis about the region.103

Hu Bo, director of the Center for Maritime Strategy Studies at Peking University, said the overall situation in the South China Sea has eased in recent years, and joint development and maritime cooperation have made solid progress in fields such as fisheries, petroleum, gas and defense. “However, conflicts and barriers begin to surface as the negotiating sides move from consensus to discussing specific details, such as drawing a territorial boundary,” said Hu, one of the authors of the report.104

For example, fishery resources are very mobile, so how to build a multilateral fishery cooperation mechanism to regulate production and conservation in the region will be challenging, he said. Oil and gas development can be even more sensitive because whichever country controls these resources will greatly bolster its economic presence in the region, Hu said. “Therefore, a preferable way is to steadily push for cooperation with bilateral participation.”105

Complicating matters, he said, the US has increased its military presence in the South China Sea in recent years under the so-called freedom of navigation operations. But Hu said he believes the focal issue of China-US contention is more about geopolitical competition than it is about sovereignty and freedom of navigation. “The US is very anxious about China’s growing naval capability and continues to wrongfully perceive it as a threat to US military dominance and a means to control the South China Sea,” he said. “It is imperative that China and the US enhance the quality of maritime strategic dialogue on substantive issues, including arms control, power structures and rules for military operations.”106

Hu said China has exercised restraint in handling the South China Sea issue. “China and the US should learn to coexist with each other in the South China Sea,” he added.107

Liu Lin, a researcher on foreign military at the People’s Liberation Army Academy of Military Science, said some ASEAN countries are trying to protect their maritime interests via military buildup and resource development in the region, as well as by attracting foreign countries to play a part in the South China Sea situation. “China will not change its fundamental relationship with ASEAN countries,” she said. “But as the negotiation for the code of conduct continues, it will inevitably touch some sensitive and complex issues, and new conflicts might occur if these issues are not handled properly.”108

Tang Pei, associate researcher at the PLA Naval Research Academy, said a handful of foreign countries are increasingly interested in stirring up tensions in the South China Sea, and their methods are becoming more sophisticated. “Many of these foreign powers are US allies, and their participation in the situation will shift the power dynamics in the region,” she said. “To what extent they are willing to follow US actions to pressure China, despite having no conflicts of interest, is still unclear and will require further research.”109

The South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative is “[w]ith a view to maintaining and promoting the peace, stability and prosperity of the South China Sea, Peking University Institute of Ocean Research has launched the South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative (SCSPI). The Initiative aims to integrate intellectual resources and open source information worldwide and keep track of important actions and major policy changes of key stakeholders and other parties involved. It provides professional data services and analysis reports to parties concerned, helping them keep competition under control, and with a view to seek partnerships”110

In 2019, the US armed forces continued to carry out intensive military activities in the South China Sea, with their strategic platforms coming in and out of the region frequently, sea and air reconnaissance forces conducting various operations vigorously, the freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) near China’s stationed islands and reefs in the South China Sea increasing rapidly, and military diplomacy intensifying unprecedentedly. Though the US has become slightly more prudent in its words and deeds with regard to the military conflicts with China in the South China Sea, its operations in this region, in terms of both scale and intensity, have been significantly reinforced, compared to those in 2018. With the continual military exercises and various drills of the US armed forces and the rushing deployment of forces and platforms in the South China Sea, the region has become a front line of the maritime strategic competition between China and the US.111

In 2019, the US military’s strategic deterrent forces, including aircraft carriers, amphibious assault ships, nuclear-powered attack submarines and strategic bombers continued to carry out intensive activities in the South China Sea, and conducted targeted deterrence patrols frequently in line with the regional situation and hotspot issues. Throughout the year, the US Navy deployed three aircraft carriers, including USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74), USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76) and USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72), and three amphibious assault ships, including USS Essex (LHD-2), USS Wasp (LHD-1) and USS Boxer (LHD-4) for military operations in the South China Sea.112

Two of the three aircraft carriers were sent to conduct targeted missions in the South China Sea, except for USS Abraham Lincoln which sailed through the waters on its way back to the US Naval Base San Diego, California after itsdeployment in the Middle East. The USS John C. Stennis, after a five-month deployment in Middle East, transited the Indian Ocean and the Malacca Strait eastbound to enter the South China Sea, and arrived in Laem Chebang,1 Thailand, for a port call on February 10. On February 14, the carrier left Thailand to conduct military operations in the South China Sea until March 5, thus making a nearly three-week stay in the region. Notably, while the USS John C. Stennis was operating in the South China Sea, the US President Donald Trump and the North Korean supreme leader Kim Jong-un met for a second summit in Hanoi, Vietnam on February 27 and 28. Therefore, the carrier was suspected of conducting pretended operations, with an aim to deter North Korea and build up momentum for the US in the summit. Shortly after the second Trump-Kim summit, the USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74) returned to the Indian Ocean and then headed to the Naval Base Norfolk in Virginia after its overseas deployment.113

Throughout the year of 2019, the USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76) conducted two patrols, one in summer and the other in fall. During its summer patrol, it came in and out of the South China Sea twice, though staying for a relatively short period in the region; while during its fall patrol, the carrier spent most of the time on targeted drills in the region, especially in the waters between the Spratly Islands and the Scarborough Shoal. Moreover, during the fall patrol, the USS Ronald Reagan, (CVN-76) formed a carrier strike group with the guided missile cruisers USS Antietam (CG-54) and USS Chancellorsville (CG-62), and the guided missile destroyers USS John S McCain (DDG-56), USS McCampbell (DDG-85) and USS Wayne E. Meyer (DDG-108), and conducted joint exercises in the waters south of the Scarborough Shoal with the P-8A Poseidon anti-submarine aircrafts deployed in Clark Air Base, Philippines for days. There have been no public records yet on the subjects of exercises performed by the P-8A Poseidon anti-submarine aircrafts and the USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76) Strike Group. However, the waters in the South China Sea are wide with an average depth of over 2,000 meters, making itself a perfect zone for both submarine warfare and anti-submarine exercises.114

On October 6, the USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76) Strike Group staged a joint exercise with the USS Boxer (LHD-4) Amphibious Ready Group which transited the waters following its Middle East deployment. This exercise coincided with the “light carrier” concept which the US Navy has been testing out. Their joint exercise, to some extent, signaled a trend of the US armed forces’ maritime warfare patterns; in particular, in regions where a dual-carrier formation is temporarily not achievable and disputes are very likely to occur, to deploy 1.5 carrier strike groups is another option.115

Among the three amphibious assault ships in the South China Sea, the USS Wasp (LHD-1) stayed longer in the region, while the other two sailed through the waters heading to the Middle East for deployment. In late March, the USS Wasp (LHD-1) entered the South China Sea and participated in the US-Philippine Exercise Balikatan on Luzon Island, Philippines from April 1 to 12. During the exercise, the USS Wasp (LHD1) carried 10 F-35B fighters of Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 121 (VMFA-121). It was the first time that F-35B fighters of the US Marine Corps (USMC) were involved in a joint exercise3 held in the Philippines after their deployment to the Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni, Japan, which is of great relevance for the US military to test out the operational capabilities of F-35B fighters in the South China Sea and its neighboring areas and help them adapt to the operational scenarios.116