By Alexander Ekemenah, Chief Analyst, NEXTMONEY

Executive Summary

- From thestandpoint of objective and empirical evidences available to this article, Democratic Republic of Congo, like many other natural resource-rich countries such as Nigeria, suffers from the deadly disease known as Dutch Disease in its mining sector, a disease that has not only led to huge revenue loss through its poor corporate governance structures but also loss of lives and destruction of destinies especially of its youth through unregulated artisanal mining over the years. It is this Dutch Disease that is the prima facie cause of the poverty of DR Congo and other unmitigated disasters amidst its natural wealth of solid mineral resources.

- Gecamines, the main body responsible for revenue collection on behalf of the Government of Democratic Republic of Congo and the administration of the mining sector, equally suffers revenue loss through corrupt practices by its officials in collusion with foreign corporate actors and economic assassination teams and also through its poor or weak financial management structure. Gecamines is the avenue through which the Congolese political elite and its foreign partners have been able to capture the resources of the State from one degree to another and over time and space.

- The deal between the Government of Democratic Republic of Congo under former President Joseph Kabila who was never elected and Chinese-owned giant mining companies in which Congo literally handed over a larger percentage of its mining leases (amounting to multibillion dollars) to the Chinese-owned mining companies in exchange for infrastructure development projects has increasingly come under intense questioning for its lack of transparency and lack of visible infrastructure project dividends in the Congo.

- The recent syndicate report by 19 international media houses and 5 non-governmental organizations called “Congo Hold-Up” coordinated by European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) on the “Platform for the Protection of Whistleblowers in Africa (PPLAAF)” including two separate reports by The Sentry titled “Embezzled Empire: How Kabila’s Brother Stashed Millions in Overseas Properties” and “The Backchannel: State Capture and Bribery in Congo’s Deal of the Century” were a mind-boggling revelation about sordid and criminal corrupt practices in the immediate past Government of Democratic Republic of Congo under former President Joseph Kabila, his family members, cronies and foreign collaborators. This has already led to the establishment of a judicial panel of investigation into the multiple allegations of criminal acts that call for the prosecution of all the accused.

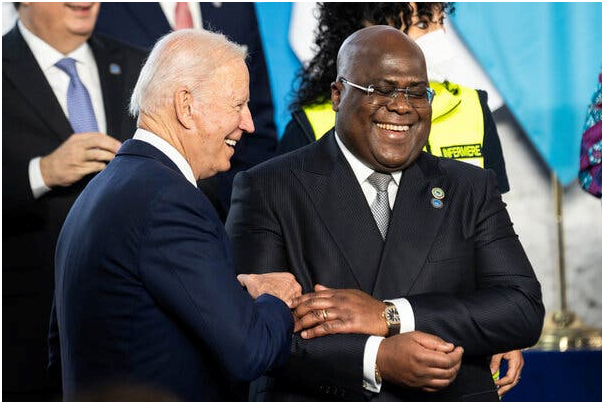

- The new government led by President Felix Antoine Tshisekedi who took over in January 2019 has embarked on a laudable review and enactment of new legal framework for mining activities in the Democratic Republic of Congo through which the government hopes to take effective control of the mining sector to the benefits of Congolese. However, the world is watching closely to see how the new mining legal code will change the hitherto unwholesome conditions in the Democratic Republic of Congo to the benefits of Congolese.

- International manufacturing companies in the field of cell phones, power banks for recharging phones, solar panels, electric vehicles among other companies are reviewing their corporate profile as regard their supply chains in order to free themselves from negative perception or direct involvement in sustaining artisanal mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo that has led to obscene child abuse, egregious human rights violations, death tolls, environmental devastations, etc. Indeed, the international manufacturing companies cannot absolve themselves of moral and legal culpabilities for the destruction of lives and environment in the Democratic Republic of Congo through artisanal mining.

- Even though there is no what can be described as geopolitical tension between the United States and China in the Democratic Republic of Congo, there is however evident rivalry between the two superpowers over the control of the mining sector in order to stockpile cobalt and other associated metals and minerals for strategic purposes especially for industrial and military usage on the one hand and for the control of political destiny of the Democratic Republic of Congo on the other hand.

- It is hoped that the current relationship between the United States and Democratic Republic of Congo the latter under President Felix Tshisekedi would enable the former to recompense for the historical injustices and atrocities hitherto committed by it during the early independence years of DR Congo. It is not just about geopolitical rivalry with another superpower or superpowers within the context of selfish national security interests of “America First” variety but the opportunity for restitution for crimes against other sovereign nations within the context of brotherhood of humanity.

Introduction

On November 20, 2021, New York Times published an article on what may be regarded as a “cobalt war” going on in the Democratic Republic of Congo between corporate mining giants and between two superpowers: United States and China.1

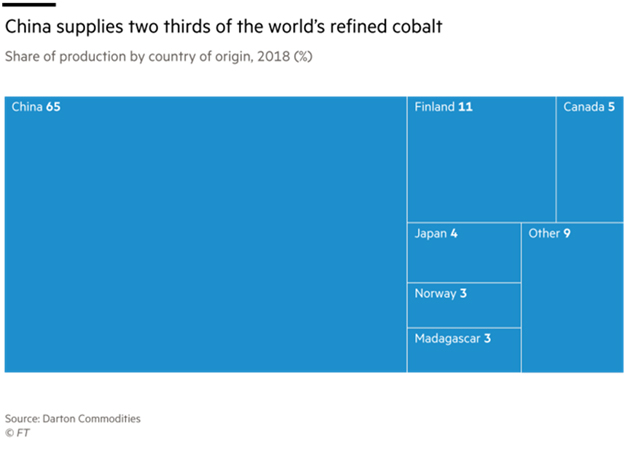

In the article, the authors noted that the ongoing clean energy revolution in the advanced economies is replacing oil and gas with a new global force: the minerals and metals needed in electric car batteries, cell phones, solar panels and other forms of renewable energy with particular reference to the Democratic Republic of Congo where cobalt and associated metals are mined and produced, and which produces two-thirds of the world’s supply of cobalt. These countries are now said to be stepping into the kinds of roles once played by Saudi Arabia and other oil-rich nations. But more significant is the fact that a race has opened up between China and the United States to secure supplies which could have far-reaching implications for the shared goal of protecting the planet.2

Some of the key findings from the insightful article include the fact that the United States has become vulnerable to price shocks and supply shortages as it goes the path thatembraces green energy; the American government failure to safeguard decades of diplomatic and financial investments it had made in Congo, even as China was positioning itself to dominate the new electric vehicle era.3

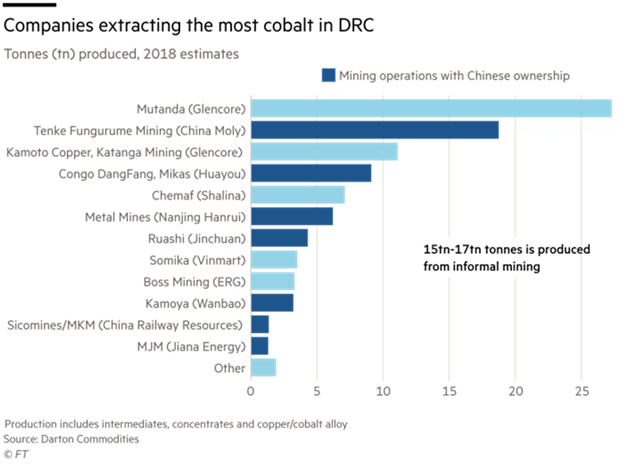

Furthermore, the sale, starting in 2016, of two major cobalt reserves in Congo by an American mining giant to a Chinese conglomerate marked the end of any major U.S. mining presence in cobalt in the country. Chinese battery makers have also forged agreements with the mining companies to secure steady supplies of the metal.4

Beijing bankrolled a buying spree of mines in Congo, locking up a key supply chain. As of last year, 15 of the 19 cobalt-producing mines in Congo were owned or financed by Chinese companies, according to a data analysis. The companies had received at least $12 billion in loans and other financing from state-backed institutions, and are likely to have drawn billions more. The five biggest Chinese mining companies in Congo that focus on cobalt and copper mining also had lines of credit from Chinese state-backed banks totaling $124 billion.5

One of the government-backed companies, China Molybdenum, which bought the two American-owned reserves, described itself to The Times as “a pure business entity” traded on two stock exchanges. Records show 25 percent of the company is owned by a local government in China. Separately, Chinese Molybdenum is being accused of withholding payments to the government [in Kinshasha] at its Tenke Fungurume cobalt and copper mine. The company said it had done nothing wrong, and questioned if there was an organized effort to undermine it.6

Congolese officials accuse Chinese mining companies of cheating the country of promised revenues and improvements. The Congolese are reviewing past mining contracts with financial help from the American government, part of a broader anti-corruption effort. They are also examining whether Chinese promises to build roads, schools, hospitals and other infrastructure were kept.7

The above is one side of the story. Actually New York Times did quite an impressive in-depth reports on the crisis in the Congolese mining sector from what may be regarded from a holistic pedestal but which also convey the impression that New York Times may be crying more than the bereaved or serving as a media or megaphone for the American Government in its renewed bid to tackle China over the mining of cobalt in Congo. But it also left many questions unanswered. For instance, why did America shift its focus from DR Congo, leaving the place for Chinese to become lords of the manor? How did China fail to deliver on its promise to help develop infrastructures in DR Congo in exchange for the humongous cobalt mining licenses granted to it earlier?

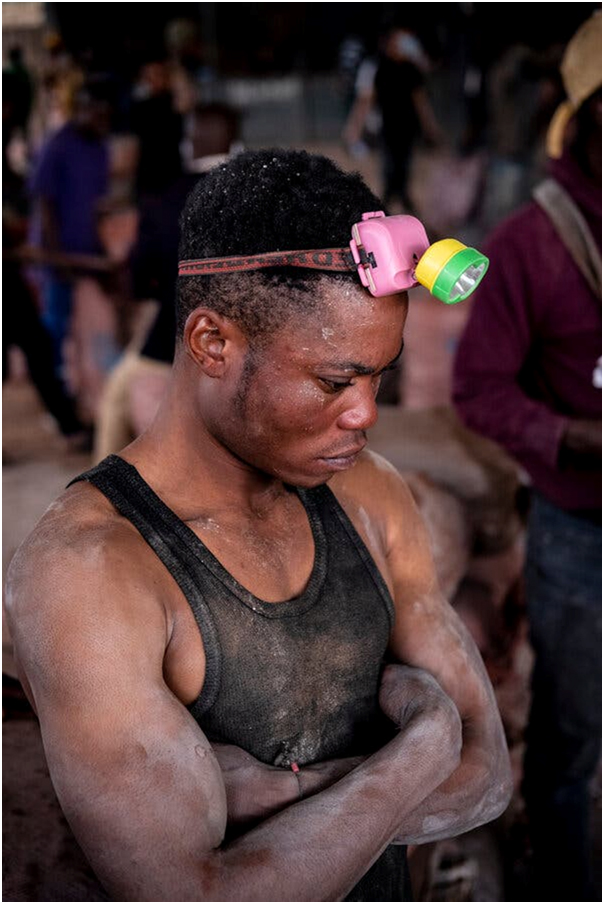

However, the other side of the story is perhaps more gloomier than the first. Nicolas Niarchos had on May 31, 2021 published an article in the New Yorker titled “Buried Dreams” detailing his several visits to Democratic Republic of Congo investigating artisanal mining of cobalt by young and old (with special emphasis on child labor), crude methods of mining, the deaths that have occurred from natural disasters such as cave-in of mines, the death tolls, the destruction of destinies, the ruthlessness of corporate mining companies and their accomplices in government and individual merchants, the undertones of racial discriminations and mutual recriminations between the laborers and their modern Chinese merchants, the destruction or disruptions of the natural and social ecosystem, the lamentations of the helpless citizens, the heart-breaking and soul-shattering poverty accompanied by superstitious beliefs, the almost non-existent primary and secondary education in the rural areas of Southern Congo, the corruption in government circles beginning from the local government to the state level including the federal government, and the ferocious battle for supremacy between the superpowers over the mining and supply of cobalt and other associated minerals, etc.

Southern Congo sits atop an estimated 3.4 million metric tons of cobalt, almost half the world’s known supply. In recent decades, hundreds of thousands of Congolese have moved to the formerly remote area. Kolwezi now has more than half a million residents. Many Congolese have taken jobs at industrial mines in the region; others have become “artisanal diggers,” or creuseurs. Some creuseurs secure permits to work freelance at officially licensed pits, but many more sneak onto the sites at night or dig their own holes and tunnels, risking cave-ins and other dangers in pursuit of buried treasure.8

Murray Hitzman, a former U.S. Geological Survey scientist who spent more than a decade travelling to southern Congo to consult on mining projects there, and who teaches at University College Dublin, explained that the rich deposits of cobalt and copper in the area started life around eight hundred million years ago, on the bed of a shallow ancient sea. Over time, the sedimentary rocks were buried beneath rolling hills, and salty fluid containing metals seeped into the earth, mineralizing the rocks. Today, he said, the mineral deposits are “higgledy-piggledy folded, broken upside down, back-asswards, every imaginable geometry—and predicting the location of the next buried deposit is almost impossible.”9

Copper has been mined in Congo since at least the fourth century, and the deposits were known to Portuguese slave traders from the fifteenth century onward. Cobalt is a byproduct of copper production. In 1885, Belgium’s King Leopold II claimed the country as his private property and brutally exploited it for rubber; according to “King Leopold’s Ghost,” a 1998 book by Adam Hochschild, as many as ten million Congolese were killed. But, because of local resistance and the inaccessibility of the region, large-scale commercial mining didn’t begin in the south until the twentieth century.10

Kolwezi was founded in 1937 by the Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, a mining monopoly created by Belgian royal decree. These colonialists may not have matched the atrocities of King Leopold, but they still saw the country in starkly exploitative terms. They understood that the best way to extract Congo’s mineral wealth quickly was to create infrastructure. The company cleared the thickets of thorny acacias and miombo trees that had grown atop Kolwezi’s rich mineral deposits and built the town across the area’s rolling hills, with wide streets and bungalows for Europeans, whose neighborhoods were segregated from those where Congolese workers lived. Locals were used to create this infrastructure, and to labor in the mines, but, as Hitzman put it, “the whites ran everything.”11

After independence, the southernmost province, Katanga, was viewed as a prize by Cold War powers. In the sixties, Katanga unsuccessfully tried to secede, with the support of Belgium and the Union Minière. Then, in 1978, Soviet-armed and Cuban-trained rebels seized Kolwezi and several hundred civilians were killed. Before the insurrection, the Soviet Union appeared to have been stockpiling cobalt, and, according to a report by the C.I.A., the attack set off “a round of panic buying and hoarding in the developed West.” Cobalt, the report declared, “is one of the most critical industrial metals.” Then, as now, the mineral was used in the manufacture of corrosion-resistant alloys for aircraft engines and gas turbines.12

The West’s solution to the market instability was to prop up the country’s dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, who presided over an almost farcically kleptocratic regime. The country’s élite sustained themselves, in part, on the profits from the mines. Gécamines, a state-controlled mining company, ran a virtual monopoly in Katanga’s copper-and-cobalt belt, and owned swaths of the cities that had been built to house miners.13

By the early nineties, Mobutu and his cronies seemed to have stolen everything they could, and Congo was falling apart. As the country drifted toward civil war, the Army pillaged Gécamines, and former workers sold off minerals and machine parts in order to feed their families. In 1997, Mobutu went into exile. The disintegration of Gécamines transformed Congo’s mining landscape. Creuseurs began digging at the company’s largely abandoned sites, selling ore to foreign traders who had stayed behind after Mobutu was deposed.14

Congo became mired in a series of wars in which more people were killed than in any other conflict since the Second World War. The country’s next leader, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, was assassinated, in 2001, and his son Joseph took over. Both Kabilas funded their war efforts by selling Gécamines sites to foreigners. By the time Hitzman arrived, in the mid-two-thousands, Gécamines had become a shell. “Some of the best geologists I’ve ever met in my life were still working for Gécamines, and hadn’t been paid for three years,” Hitzman said. “It was sad as hell.”15

Of course, it is not only the New Yorker or the New York Times that have documented the sufferings of the artisanal miners in the Congo. Several other international media houses and international non-governmental organizations have come out with their various reports over the last few years displaying a panoramic or landscape view of the sufferings of miners behind the exploitation of cobalt and other resources in the Congo.

The snail-pace or gradual shift from non-renewable fossil fuels such as petrol and other fossil fuels to renewable energy largely because of the advent of new technologies in the energy field and also over the growing concern about climate change has brought the exploitation of cobalt and other associated metals and minerals into the foreground of technological development as well as media publicity. Thus behind the ubiquitous trendy mobile handsets worldwide, the laptops, solar panels, and fashionable electric vehicles, including defense and industrial products, has brought Democratic Republic of Congo into global reckoning. But mostly unknown to the end-users of these products, lies the enormous suffering of millions of people in the Democratic Republic of Congo that has the largest deposits of this strategic solid mineral resource in the world.

Unfortunately, the worst part of it is that neither Democratic Republic of Congo nor other such solid mineral resource-rich countries are ever anywhere near Saudi Arabia or other oil-producing countries in terms of economic development or growth pattern. That was the gross misconception and deficit in the analysis of New York Times article referenced above. The tragic fact is that Democratic Republic of Congo has no domesticated manufacturing based on extraction and/or production, processing and refinement of cobalt and other associated metals and minerals – except excavation sites of cobalt that have left the ecosystem devastated in terms of environmental degradation and lives and destinies of millions of artisanal miners destroyed or upended. There are no localized manufacturing bases based on these solid mineral resources to strengthen the DRC economy to, in turn, strengthen its productive and sustainable capacity in an economy of scale and value chain. There is no manufacturing base for batteries anywhere in DRC. There is no electric vehicle assembly plant; no mobile phone assembly plant or solar panel assembly plant that creates their individual value chains.

The old colonial mentality still prevail where the former colonial countries continue to supply raw materials to the metropolitan centres of the West or North including the East now upon demand who in turn continue to claim the ownership of superior technology for turning these raw materials to finished products to be resold back to the developing countries at higher prices. The prices for these raw materials are largely determined by the buyer countries through the global market forces of which they are fully in control or in charge. The advance forces of knowledge in turning these raw materials into finished products still reside with the buyer countries.

Thus despite the fact that DRC has largely conceded its sovereign rights to own, produce, process and refine these strategic metals and minerals in a manufacturing cycles, i.e. battered its sovereign rights as pot of mess to foreign countries and international mining giants on the premise and promise of infrastructure development in return for these acts of Prodigal Son, the DRC economy has not shown any sign of sustainable development and growth pattern and there is no future trajectory upon which to predicate the suicidal policy act of self-destruction. Political stability is still largely a mirage. The earth beneath the Congo is not only suffering from quakes of artisanal mining, but one can feel political earth tremors still growling or snarling at the incompetence of political leadership that has plunged the nation into unmitigated disaster with their puny brains. Indeed, in the holistic ontology of DRC, there is hardly a difference between the dictatorial regimes of Mobutu Sese Seke and the two Kabilas in their venal corruption and gross incompetence in managing natural and human resources with which DRC has been endowed.

On the other hand, despite the recent effort at re-aligning the mining sector to the maximum advantages of the Congo via the new mining legal code and framework including reforms of Gecamines and other relevant institutions, political disputes among the various contending groups have largely stalled this necessary effort. These political disputes and rivalries were succinctly captured by Africa Confidential when it reported in late April 2021 that “A new government plans to transform its finances and take on rebel groups but is reliant on a band of political godfathers Announcing hundreds of planned initiatives, Congo-Kinshasa’s new government has lofty ambitions, but its main challenge may simply be staying together. Its four vice-prime ministers, each from a different faction of the ruling coalition, have different political godfathers to serve, including the President’s main rival, his predecessor Joseph Kabila.16

Background

The world may not have been hitherto fully aware of the enormity of the crisis involved in the mining of cobalt and other associated metals and/or minerals in the Democratic Republic of Congo until the last few years. Even the news reportage emerging on DRC from international media houses may not have accurately captured the gravity of the crisis. But the global corporate miners, and the government of DRC, are no doubt fully aware but keeping largely quite about it for fear of being called to public accountability. However, they are already being called out.

First, the advent of information technology itself especially internet has inevitably helped to spread the awareness through media reportage, media and scholarly researches into the general problems associated with mining of cobalt and other mineral resources in DRC including other countries particularly in connection with problem of artisanal mining.

Second, the advent and evolution of smart technologies such as GSM and the associated mobile telephony (handsets), the energy mix producing solar energy through the solar panel techs, the emergence of electric vehicles of all varieties, not to talk of advance defense and heavy industrial requirements – all these have come to increase demand for cobalt and associated solid mineral resources wherever they may be found.

Third, the increasing outcries by international non-governmental organizations, human rights bodies and agencies including the local and international media houses against the wholesale problems presented by mind-boggling crude artisanal mining methods with the resultant loss of lives and destruction of destinies of young and old over the years, the exploitative ruthlessness of corporate mining giants, the egregious violation of human rights of the citizens including child abuses in the name of building infrastructures by governments and security services has brought the issue of cobalt mining in DRC to the foreground of international debate.

Cobalt is an essential mineral used for batteries in electric cars, computers, and cell phones. Demand for cobalt is increasing as more electric cars are sold, particularly in Europe, where governments are encouraging the sales with generous environmental bonuses.17

More than 70 percent of the world’s cobalt is produced in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and 15 to 30 percent of the Congolese cobalt is produced by artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). For years, human rights groups have documented severe human rights issues in mining operations. These human rights risks are particularly high in artisanal mines in the DRC, a country weakened by violent ethnic conflict, Ebola, and high levels of corruption. Child labor, fatal accidents, and violent clashes between artisanal miners and security personnel of large mining firms are recurrent.18

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. Like nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth’s crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, produced by reductive smelting, is a hard, lustrous, silver-grey metal.19

Cobalt-based blue pigments (cobalt blue) have been used since ancient times for jewelry and paints, and to impart a distinctive blue tint to glass, but the color was for a long time thought to be due to the known metal bismuth. Miners had long used the name kobold ore (German for goblin ore) for some of the blue-pigment-producing minerals; they were so named because they were poor in known metals, and gave poisonous arsenic-containing fumes when smelted. In 1735, such ores were found to be reducible to a new metal (the first discovered since ancient times), and this was ultimately named for the kobold.20

Today, some cobalt is produced specifically from one of a number of metallic-lustered ores, such as cobaltite (CoAsS). The element is, however, more usually produced as a by-product of copper and nickel mining. The Copperbelt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Zambia yields most of the global cobalt production. World production in 2016 was 116,000 tonnes (114,000 long tons; 128,000 short tons) (according to Natural Resources Canada), and the DRC alone accounted for more than 50%.21

Cobalt is primarily used in lithium-ion batteries, and in the manufacture of magnetic, wear-resistant and high-strength alloys. The compounds cobalt silicate and cobalt(II) aluminate (CoAl2O4, cobalt blue) give a distinctive deep blue color to glass, ceramics, inks, paints and varnishes. Cobalt occurs naturally as only one stable isotope, cobalt-59. Cobalt-60 is a commercially important radioisotope, used as a radioactive tracer and for the production of high-energy gamma rays.22

Cobalt is the active center of a group of coenzymes called cobalamins. Vitamin B12, the best-known example of the type, is an essential vitamin for all animals. Cobalt in inorganic form is also a micronutrient for bacteria, algae, and fungi.23

The child labor (a phenomenon largely abhorred in the advanced Western countries) involved in artisanal scale mining of cobalt in the DRC because of the extreme general poverty of the country as a whole over the decades has been a sore point in the febrile debate now unfolding over cobalt mining and the ferocious battle for supremacy between two giants: the United States and China.

According to Amnesty International, a global non-governmental organization focused on human rights, the Congolese government confirmed estimates that roughly 20% of the cobalt exported from the country was of ASM origin as recently as 2016. Other research, done by Belgian geologists, estimated that as much as 60% of the DRC’s cobalt exports were sourced through ASM in 2011. This method of mining was also linked to human rights violations, predominantly issues of child labor and worker exploitation.24

The potential for negative impacts on households that relied on artisanal mining for subsistence further complicated any proposed solution to human rights issues in the supply chain. According to the report, 60% of those surveyed relied on artisanal mining for their livelihood.25

While the artisanal mining of cobalt in the DRC had been linked to negative health outcomes, such as the increased risk of exposure to uranium and even death, it also provided subsistence for those struggling with access to adequate food, water, and housing. Artisanal mines could provide an environment that was ripe for exploitation by militant groups who sought to use cobalt profits to finance violence within the country. Such exploitation was well documented for other materials, like coltan, a mineral that contains tantalum; an important metal used in consumer electronics as a material for capacitors.26

But the demand for cobalt is practically unstoppable. According to James Conca, “unfortunately, the demand for Co is increasing like a bacteria culture in a petri dish, and poor children are its food.”27The reason this is so important is that many of the people who support the new energy technological revolution of non-fossil fuels, renewables and new nuclear SMRs, electric vehicles, conservation and efficiency, also care about the social issues that many of these technologies incorporate in their wake – corruption, environmental pollution, extreme poverty and child labor.28 And the supply of Co is the perfect intersection of these two issues.29

James Conca further revealed that “unfortunately, the Democratic Republic of Congo is pervaded by conflict, poverty and corruption. The country’s economy is completely dependent on mining. Many poor families are completely dependent on their children working the mines. That $9/day is hard for a child to reject. Competing jobs pay even less, and there are few of those.30

Western tech giants like Tesla, Apple, GM, Samsung and BMW consciously ignored the problems surrounding child labor and corruption because consumers didn’t seem to care and just wanted the latest devices as fast as possible. Co is a preferred component in lithium-ion batteries that power laptops, cell phones, and electric vehicles, and these exploding applications are causing the use of Co to skyrocket.31

In 2016, Amnesty International issued a blistering report naming more than two dozen electronics and automotive companies that had failed to ensure their cobalt supply chains didn’t include child labor at these types of mines.32 [Unfortunately], just like blood diamonds and the garment industry’s child sweatshops, it takes time and the shining of light on these practices before the Western public starts to care.33

While the majority of Congo’s cobalt comes from large mining sites where rock is dug up by trucks from the bottom of deep pits, a growing proportion is coming from an estimated 150,000 “artisanal” or informal miners who dig by hand in Kolwezi.34

And last year [2018] accounted for an estimated 30 per cent of Congo’s cobalt — the country mines more than 70 per cent of the global total — according to Gecamines, Congo’s state-owned miner. Congo’s dominance presents a growing dilemma for carmakers and those in the supply chain as they look to meet a rapid increase in demand for electric vehicles and batteries. If they try to improve conditions on the ground they face a series of additional risks, from the threat of corruption to monitoring and enforcing measures to avoid deaths from informal mining and the presence of children on these sites. And while manufacturers cannot afford to ignore Congo they must also know that untraceable metal — from these informal miners — leaks into the global supply chain via refineries in China, ending up in batteries, cars and smartphones sold in the West.35

Thanks in part to high cobalt prices in 2018; a lot of this activity now takes place within the sites of the large mining groups, including Switzerland-based Glencore and Hong Kong-listed China Molybdenum, which sprawl across large areas of border villages. In June 43 informal miners died when part of a pit collapsed at Glencore’s largest mine outside Kolwezi. State authorities sent the army to the site as well as China Moly’s giant copper and cobalt mine 90km east in Tenke Fungurume to remove up to 10,000 informal miners who were trespassing. “A lot of people [buyers] realise they can no longer shut their eyes and pretend it’s not happening, which was the strategy for quite a while,” says Indigo Ellis, an Africa analyst at Verisk Maplecroft.36“There are no real viable alternatives to cobalt from the DRC at the moment so they will have to start engaging with it.”37

Congo Dongfang International Mining, a subsidiary of Zhejiang Huayou, a Chinese conglomerate that, among other things, has supplied materials for iPhone batteries. China is the world’s largest producer of lithium-ion batteries, and Huayou has made a huge investment in Congo. After acquiring mineral rights in the region, in 2015, it built two cobalt refineries. According to an internal presentation, by 2017 Huayou controlled twenty-one per cent of the global cobalt market.38

China and Congo have a long history. During Leopold’s reign, Chinese workers were shipped to Congo to help build the national railroad. In the nineteen-seventies, Mobutu turned to Mao’s regime for technical collaboration on infrastructure projects. By the nineties, the Chinese were becoming the bosses: the Beijing government and myriad Chinese businesses began making heavy investments in Africa, particularly in resource-rich and regulation-poor countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Peter Zhou, a Chinese-born financier who has worked on a few mining deals in Congo, said that in such countries “there is corruption; there is lack of the rule of law, which gives you more autonomy to be entrepreneurial.” (Zhou emphasized that he hadn’t directly witnessed or engaged in corruption.) In 2007, Joseph Kabila made a six-billion-dollar infrastructure deal with China that included a provision allowing the Chinese to extract six hundred thousand tons of cobalt.39

In 2016, China Molybdenum paid the U.S. company Freeport-McMoRan $2.65 billion for a controlling stake in Tenke Fungurume, a giant copper-and-cobalt mine about two hours east of Kolwezi; three years later, China Molybdenum acquired another stake, for $1.14 billion.40

Huge sums of money continue to change hands in the region. In December, China Molybdenum paid Freeport-McMoRan half a billion dollars to acquire a controlling stake in Kisanfu, a copper-and-cobalt concession east of Kolwezi. At a recent conference sponsored by the Financial Times, Ivan Glasenberg, the C.E.O. of Glencore, said, “China, Inc., has realized how important cobalt is.” He continued, “They’ve gone and tied up the supply.” He warned that if Chinese companies stopped exporting batteries, this could hamper the ability of non-Chinese companies to produce electric vehicles. Last month, CATL, a Chinese conglomerate that develops and manufactures lithium-ion batteries, acquired a hundred-and-thirty-seven-million-dollar stake in the Kisanfu mine. Tesla works with the company to make its car batteries, and CATL has supplied batteries to Apple. Recently, according to witnesses at Kisanfu, a cave-in killed at least four creuseurs.41

Zhou acknowledged that there was “a lot of corruption” in Congo’s mining sector, but he maintained that, with enough economic prosperity, the gray economy in Congo will fade, much as it has in China.42

Multiple problems are generated as a result of unregulated artisanal mining, showing the little social control DRC has over its own population. Environmental disasters such as mining cave-ins, destruction and dislocation of villages, deaths of many children involved in artisanal mining, clashes between miners and security forces from time to time, the low prices or wages received from the mining giant companies, the imperviousness of the Government in Kinshasha and other state and local capitalsare daily stuff in media reportage.

Both the primitive and modern Shylock system of profit extraction are described by Financial Times of London published in July 2019:

After the 40-hectare area in Kasulo was cleared of houses a perimeter wall was erected around the site and a security gate introduced to check miners on arrival. A Chinese security guard points proudly to a sign that says no children or drinking are allowed on site. Tunnels still dot the roughshod land but pits have already been dug for the miners.43

About 600 miners work on the site, down from around 5,000 last year, though this is partly due to the fall in cobalt prices from a 10-year high of over $40 a pound in early 2018 to $13.50 a pound, according to Fastmarkets. The miners are organised into co-operatives which take a cut of the number of bags sold by the workers in return for assistance such as covering medical bills, helping family members in the case of death and representing the miners at political meetings. After digging the cobalt, the miners take their sacks to be crushed, weighed and graded in on-site depots, after which the material is authenticated and sold to local traders and then to Huayou.44

The relocation of the villagers triggered protests and has been opposed by some organisations in Kolwezi. Questions have been raised about who controls the co-operatives. The Good Shepherd charity, which helps children leave mine sites by providing free schooling, decided to end its engagement with Huayou over concerns about the relocation of the residents and their compensation packages. Emmanuel Umpula Nkum of African Resources Watch, a local non-governmental organisation, says local miners should be able to sell their cobalt to whoever they want to rather than being forced to sell all their metal to one company, Huayou.45“We need zones where the miners should be in co-operatives created by themselves and where they can work and sell their minerals to buyers,” he says. “We need them to have the possibility to say ‘this is not a good price’ and go elsewhere to sell their minerals.” Distrust remains high. Some miners recently broke in and damaged the platform that weighs cobalt trucks, angry at the lower prices for their metal. And no sooner had the Kasulo project begun than a new site opened up outside its walls.46

There are around 200,000 informal copper and cobalt miners in the DRC.47In April [2019] BMW told an OECD conference that it would source its cobalt for its electric cars from Morocco and Australia and not the DRC. Belgian-based Umicore, the largest producer of battery materials in Europe, whose predecessor company Union Minière recruited forced labour to mine copper in the region in the early 20th century, says it does not buy from informal sites in the country. Instead, in May Umicore announced a long-term deal to buy cobalt from Glencore’s mines in Kolwezi.48

Plummeting cobalt price takes toll on Democratic Republic of Congo “We are supportive of industry efforts to engage with the mining community, despite the risk. The challenge is how to manage that risk and communicate it properly. Disengagement is not the right approach, but the threat of disengagement has to be real and combined with technical and financial support to drive improvement.” Swiss commodity trader Trafigura, which is one of the largest buyers of Congolese cobalt and copper, says artisanal-mined minerals can be a source of supply for carmakers.49

When Trafigura signed a three-year deal to buy all the cobalt produced from DRC-based Chemaf last year, it faced the problem of how to manage the more than 5,000 informal miners working on the site near Kolwezi. Miners were regularly dying in tunnels that went as deep as 100m into the earth, recalls James Nicholson, head of corporate responsibility at Trafigura.50

Congo has a limited window of time to fix its informal mining problem before cobalt is replaced in electric car batteries by other minerals, he says. “Our preference is not to ignore it, it’s to find solutions,” he adds. “If we can be a bit creative in developing controls then we could avoid the product just dripping out into the market. We can sell the product as long as our counterparties are well aware of what they are receiving.”51

Nicholas Garrett, chief executive of RCS Global, says companies and consumers are aware of issues in the electric vehicle and battery supply chain. “Emotionally an EV is supposed to be a good deed — you’re buying an EV you’re thinking you are saving the planet — the last thing you want to hear is that the car is not clean,” he says. “Companies who works with us are starting to understand what the risks are — and asking what do we do about it. But this is an enormous challenge as we’re starting at such a low base: if people aren’t dying and there are no children then that’s a positive.”52

The companies that use lithium-ion batteries periodically respond to public pressure about the conditions in cobalt mines by promising to clean up their supply chains and innovate their way out of the problem. There is also a financial incentive to do so: cobalt is one of a battery’s most expensive elements.53

Last year, Tesla pledged to use lithium-iron-phosphate batteries, which do not contain cobalt, in some of its electric cars. Huayou stock plummeted.54 Still, Reuters noted, “it was not clear to what extent Tesla intends to use L.F.P. batteries,” and the company “has no plans to stop” using batteries that contain cobalt. (L.F.P. batteries aren’t used in cell phones: to achieve the required voltage, the batteries would have to be doubled up, adding unacceptable bulk and heft.)55

Statement of the Problem

Ms Aileen Hantverk, the director of sustainability for Samsonic, a global technology company that manufactured, among other products, lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles was reported to have listened to a podcast while commuting through Metro Detroit in which the following statement was noted “The fate of EVs and that of the DRC are effectively intertwined… Without the DRC, the projected global growth of EVs will not materialize. Likewise, without the sustainable deployment of EVs, the DRC may not realize a different trajectory as a nation.”56

The Democratic Republic of Congo is the world’s leading producer of cobalt, a commodity of which the demand has tripled during the last decade. In 2010, cobalt from Katanga Province ensured half of the global cobalt primary production. During the last decade, 60 to 90% of this cobalt stemmed from artisanal mining. Refined cobalt applications include metallurgical superalloys and booming chemical applications such as batteries for electronic devices and electric cars.57

During a decade of wars and political instability, while industrial production had collapsed, tens of thousands of artisanal miners started exploiting heterogenite (a cobalt ore) in the province of Katanga. They supplied foreign traders (mainly Chinese), and the smelting facilities of the state-owned GECAMINES. Despite very basic working conditions, locals and migrants from other provinces were able to make a living of digging in the relatively peaceful South-East of the country. In 2002,however,asithadtoraiseloansfrommultilateralandbilateraldonors, the transition government of DRC entered a privatization process of the huge copper, cobalt and other mineral reserves belonging to the GECAMINES. A new mining code was promulgated in order to attract investors. The establishment of major mining companies excluded artisanal miners from large tracks of land that they could previously exploit, as foreign investors wanted to secure their assets and were unwilling to be liable for artisanal activities under precarious working conditions. Forced evictions not only resulted in violent protests but also animosity with local authorities who are often known for despising mining communities because of their “immoral” reputation. Being aware of the threat that 100,000 unsatisfied miners represent for political stability – and under the pressure of international public opinion – the state and some private companies, together with civil society, have been making efforts in the last years to solve the social problems arising from artisanal mining, which were only partially successful. Although it does not currently possess the capacity to refine the major part of its production, the D.R. Congo remains an indispensable supplier of raw cobalt ore for the years to come.58

Ominously, the DRC has a history of being exploited for its natural resources, first by the Belgian colonial regime, then mining corporations and foreign powers that were deeply involved in the First and Second Congo Wars.59

The latter war (1998-2003) drew in multiple countries across the continent. The fighting mostly abated after a series of shaky peace accords but government forces and militia groups are still involved in ongoing insurgencies and conflicts with resource extraction fuelling militia violence and weapons purchases. Lack of governance capacity and issues of corruption and clientelism have led to difficulties implementing any meaningful mining regulations.60

Most of the cobalt in the DRC is located in the former Katanga province (which was split into Tanganyika, Haut-Lomami, Lualaba and Haut-Katanga provinces in 2015) in the country’s far south. Katanga’s rich resource wealth has driven political events in the DRC for decades. For instance, Katangan secessionists were heavily involved in the 1961 killing of Patrice Lumumba, the Congolese independence leader and the DRC’s first prime minister.61

The region is still experiencing instability, with an ongoing separatist insurgency driven by discontent over the perceived lack of return on mineral wealth. Intercommunal violence and conflict between Mai Mai militants and government forces has displaced a quarter of a million people in Lualaba—where the largest cobalt mines are located—since July 2016. But cobalt does not only affect the southern DRC. Its significant worth and importance in the changing global political-economy could undermine institutions and security conditions across the DRC.62

Like other African countries, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has a centuries-long history of colonization and exploitation by European and American powers. Pre-colonization, the region was known as the Kongo Kingdom. This was a successful agricultural mercantile civilization that arose during the early 1400s63

But in the post-independence years, Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) has utterly failed both at the political and corporate governance level to turn DRC into a UAE-like country. Its colossal failure has turned the country into a battle ground between rival superpowers. And as an African saying goes: where two elephants fight, it is the grass that would inevitably suffer. The failure of governance in DRC has turned the country into a pit of hell for the masses of the citizens. Artisanal miners and their sufferings are collateral damages for this failure of governance. In the over sixty years of its independence, DRC has only had five leaderships: Patrice Lumumba, Mobutu Sese Seko, Laurent-Desire Kabila, Joseph Kabila and Felix Tshisekedi. Both Lumumba and Laurent-Desire Kabila’s governments were short-lived and their governments were violently terminated by reactionary forces (both external and internal) that did not ostensibly want to see their faces.

There has been no visible paradigm shift in national focus and policy attitude on the part of the Government of DRC since the early independence years especially after President Mobutu Sese Seko was overthrown in 1997 and was forced into exile where he finally died. Democratically elected Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba was hardly in power in the early 60s and was given no chance to showcase his national economic policy blueprint before he was brutally assassinated – assassination orchestrated by the US Government of that time in alliance with Belgian forces and internal forces. Lumumba was replaced by Mobutu Sese Seko who became one of the longest ruling and most brutal dictators Africa ever knew. Mobutu was eventually overthrown after a protracted civil war and Laurent-Desire Kabila emerged in May 1997. He was also hardly in power (less than five years) before he was brutally assassinated by his compromised bodyguards on January 16, 2001. His son, Joseph Kabila, in his late 20s emerged as the new leader and thus raising hopes to the high heavens among African youth about the possibility of leadership role it could play in changing the African political landscape and corporate governance.

To whom much is given either by Providence or historical circumstances, much is expected. But Joseph Kabila ended his tenure in office as a huge disappointment for been a resounding failure for the inability of his government to resolve fundamental problems of mining in the Congo upon which much of the economic development is predicated and dependent. The younger generations who have hitherto looked up to him as an inspirational figure in a continent heavily populated by tired and effete old men who cling to power by all means possible or available to them came away from his administration utterly disappointed. In the last twenty years, there is no indication that Congo can be turned into a Saudi Arabia or Qatar or UAE-like kingdom given the myopic worldview and convoluted mindset of the Congolese ruling elite. United Arab Emirates is already sending satellite into geostationary orbit where DR Congo is still mired in political conflicts and ethnic rivalries. The little revenue accrued from the mining sector has largely been squandered even when the government claims it is pursuing infrastructure development for the country.

For the Congolese leadership and political elite, it has been business-as-usual with no fundamental vision to change course for a new Congo. The laizzes-faire or layback attitude has been what has been responsible for the sordid of affairs in the Congo in which thousands of children have perished in the artisanal mines. There has been no serious attempts to correct historical injustices that have rendered Congo helpless or impotent in even carrying out minimum social reforms at the behest of its people – for instance, finding a social safety net to divert children and youth from going into artisanal mining which has often serve as their Waterloo.

The Congolese leadership has failed to bring about democratic dividends despite the so-called relative peaceful transition of power from one administration to another, for instance, from Joseph Kabila to Felix Tshisekedi. Congo is not the largest democracy in Africa neither has it even consolidated democratic rule despite being called a “Democratic Republic”.

On the economic front, there have been no turnarounds for the majority of the Congolese citizens. Congo is one of the poorest countries in the world. With the kind of natural resources with which Congo has been endowed by God or Nature, one would have expected Congo to have turned into an earthly Paradise, a proverbial replica of Garden of Eden. Tragically, Congo is akin to an amputee, hobbling along with begging bowl on the streets. Almost 40-year civil conflict stoked by petty rivalries among the various ethnic groups and political factions and sustained by global superpowers without moral consideration have contributed to rendering Congo paralyzed to the point of being unable to carry out independent reforms for the welfare of Congolese citizens. Congo has been stripped to the bones most especially by the global mining companies and other international economic assassination teams. Congo lives and survives by crumbs thrown pitifully at it.

The Congolese incapacity to refine its own minerals speaks volume and directly to the non-existence of a scientific and technical cadre serving as human capitalpool and in turn serving as knowledge resource base and force for such refineries. Again, this goes directly to the intellectual capacity of its overall educational system or facilities to produce such scientific and technical cadre. Thus the Congolese crisis is of composite nature, complex or multidimensional.

Congo has almost an unequaled rich human and natural heritage.

The Congo Basin makes up one of the most important wilderness areas left on Earth. At 500 million acres, it is larger than the state of Alaska and stands as the world’s second-largest tropical forest.64

A mosaic of rivers, forests, savannas, swamps and flooded forests, the Congo Basin is teeming with life. Gorillas, elephants and buffalo all call the region home. The Congo Basin spans across six countries—Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.65There are approximately 10, 000 species of tropical plants in the Congo Basin and 30 percent are unique to the region. Endangered wildlife, including forest elephants, chimpanzees, bonobos, and lowland and mountain gorillas inhabit the lush forests. 400 other species of mammals, 1,000 species of birds and 700 species of fish can also be found here.66

The Congo Basin has been inhabited by humans for more than 50,000 years and it provides food, fresh water and shelter to more than 75 million people. Nearly 150 distinct ethnic groups exist and the region’s Ba’Aka people are among the most well-known representatives of an ancient hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Their lives and well-being are linked intimately with the forest.67The Congo Basin’s rivers, forests, savannas, and swamps teem with life. Many endangered species, including forest elephants, chimpanzees, bonobos and lowland and mountain gorillas live here.68

Humans have inhabited the forests of the Congo Basin for tens of thousands of years. Today, the Congo Basin provides food, medicine, water, materials and shelter for over 75 million people. Among some 150 different ethnic groups, the Ba’Aka, BaKa, BaMbuti, Efe and other related groups—often referred to as Pygmies—are today’s most visible representatives of an ancient hunter-gatherer lifestyle. They possess an incredible knowledge of the forest, its animals and its medicinal plants.69

Most people in the Congo Basin remain heavily dependent on the forest for subsistence and raw materials, as a complement to agricultural activities. As populations rise, pressure on forests continues to increase. Forest edges of the forest-savanna mosaic bear the brunt of the population density, along with the banks of the larger navigable rivers, including the Congo and Ubangi Rivers.70

Construction of roads has greatly facilitated access to the interior of the forest, and many people have relocated close to roads. But logging, oil palm plantations, population growth and road development have strained the traditional resource management system.71

The Congo is the Earth’s second largest river by volume, draining an area of 3.7 million square kilometers (1.4 million square miles) known as the Congo Basin. Much of the basin is covered by rich tropical rainforests and swamps. Together these ecosystems make up the bulk of Central Africa’s rainforest, which at 178 million hectares (2005) is the world’s second largest rainforest.72

While nine countries (Angola, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Zambia) have part of their territory in the Congo Basin, conventionally six countries with extensive forest cover in the region are generally associated with the Congo rainforest: Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. (Technically most of Gabon and parts of the Republic of Congo are in the Ogooue River Basin, while a large chunk of Cameroon is in the Sanaga River Basin). Of these six countries, DRC contains the largest area of rainforest, with 107 million hectares, amounting to 60 percent of Central Africa’s lowland forest cover.73

The Congo rainforest is known for its high levels of biodiversity, including more than 600 tree species and 10,000 animal species. Some of its most famous residents include forest elephants, gorillas, chimpanzees, okapi, leopards, hippos, and lions. Some of these species have a significant role in shaping the character of their forest home. For example, researchers have found that Central African forests generally have taller trees but lower density of small trees than forests in the Amazon or Borneo. The reason? Elephants, gorillas, and large herbivores keep the density of small trees very low through predation, reducing competition for large trees. But in areas where these animals have been depleted by hunting, forests tend to be shorter and denser with small trees. Therefore it shouldn’t be surprising that old-growth forests in Central Africa store huge volumes of carbon in their vegetation and tree trunks (39 billion tons, according to a 2012 study), serving as an important buffer against climate change.74

Congo has turned none of the above natural environment into economic and social advantages. Congo, apart from the mining sector that attracts all manners of flies like honey, is mostly a no-go country for tourists because of ethnic conflicts and ecological devastations.

Countries, as well as corporate bodies and individuals, are largely defined by the choices and decisions they make over the arch of time and space. Congo has not shown any choice or decision made since independence that alter the economic balance of power in favor of the Congolese citizens. Its economic soul has been battered on the basis of lack of capacity by the political leadership to come up with pro-people or people-centered choices and decisions. Western or Northern powers including multinational companies, well-practiced in science and arts of governance including sophisticated knowledge of the fundamental weaknesses of political leadership in the developing countries, have been able to move in lock-steps with the various leaderships in the developing countries, manipulating them unscrupulously to the benefits of the advance countries and to the detriments of the developing countries.

Thus Congo, hard as this may sound, is a colossal strategic failure for not been able to serve its own citizens and also for not been able to protect the sovereignty of its own State against the ravages of foreign vampires.

The Geostrategic Context

Oil has hitherto been the major driver of the Third Industrial Revolution upon which much of the current global economic development has been built. But the impacts of the Third Industrial Revolution on the ecosystem or in short global climate, the politics involved at all levels, the advancement in new science and technology has inevitably brought what is now known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution into being. And the world is catching and latching on to this new bandwagon of Fourth Industrial Revolution which has become inescapable for all.

Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman, World Economic Forum, wrote as far back as early 2016 that “We stand on the brink of a technological revolution that will fundamentally alter the way we live, work, and relate to one another. In its scale, scope, and complexity, the transformation will be unlike anything humankind has experienced before. We do not yet know just how it will unfold, but one thing is clear: the response to it must be integrated and comprehensive, involving all stakeholders of the global polity, from the public and private sectors to academia and civil society.75

The First Industrial Revolution used water and steam power to mechanize production. The Second used electric power to create mass production. The Third used electronics and information technology to automate production. Now a Fourth Industrial Revolution is building on the Third, the digital revolution that has been occurring since the middle of the last century. It is characterized by a fusion of technologies that is blurring the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres.76

There are three reasons why today’s transformations represent not merely a prolongation of the Third Industrial Revolution but rather the arrival of a Fourth and distinct one: velocity, scope, and systems impact. The speed of current breakthroughs has no historical precedent. When compared with previous industrial revolutions, the Fourth is evolving at an exponential rather than a linear pace. Moreover, it is disrupting almost every industry in every country. And the breadth and depth of these changes herald the transformation of entire systems of production, management, and governance.77

The possibilities of billions of people connected by mobile devices, with unprecedented processing power, storage capacity, and access to knowledge, are unlimited. And these possibilities will be multiplied by emerging technology breakthroughs in fields such as artificial intelligence, robotics, the Internet of Things, autonomous vehicles, 3-D printing, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science, energy storage, and quantum computing.78

Already, artificial intelligence is all around us, from self-driving cars and drones to virtual assistants and software that translate or invest. Impressive progress has been made in AI in recent years, driven by exponential increases in computing power and by the availability of vast amounts of data, from software used to discover new drugs to algorithms used to predict our cultural interests. Digital fabrication technologies, meanwhile, are interacting with the biological world on a daily basis. Engineers, designers, and architects are combining computational design, additive manufacturing, materials engineering, and synthetic biology to pioneer a symbiosis between microorganisms, our bodies, the products we consume, and even the buildings we inhabit.79

It is partly due to the waning influence of oil and the advent of new technological revolution that have now brought about the increased pressure on the use of cobalt and other associated strategic minerals along with their specific individual advantages over other types of minerals.

Of course, cobalt has its own usage over the arch of time and space or history.

Ores containing cobalt have been used since antiquity as pigments to impart a blue colour to porcelain and glass. It was not until 1742, however, that a Swedish chemist, Georg Brandt, showed that the blue colour was due to previously unidentified metal, cobalt.80

In 1874 the output of cobalt from European deposits was surpassed by production in New Caledonia, and Canadian ores assumed the leadership about 1905. Congo (Kinshasa) has been a dominant world producer since 1920. In the early 21st century, China was the leading producer of refined cobalt, most of which originated in Congo (Kinshasa). Other important producers included Russia, Australia, and the Philippines.81

Prior to World War I most of the world’s production of cobalt was consumed in the ceramic and glass industries. The cobalt, in the form of cobalt oxide, served as a colouring agent. Since that time, increasing amounts have been used in magnetic and high-temperature alloys and in other metallurgical applications; about 80 percent of the output is now employed in the metallic state.82

Cobalt, a bluish-gray metal found in crustal rocks, has many uses in modern society. Cobalt is mined all over the world, but over half of the global Co supply comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo.83

Besides batteries, the metal is used in magnetic steels, high-speed cutting tools, and in alloys used in jet turbines and gas turbine generators. For thousands of years Co was used as a pigment to get rich blue colors as well as violet and green, and is used in modern dyes and in electroplating because of its appearance, hardness, and resistance to corrosion. Co is also made radioactive for use in medicine, particularly to treat cancer and as a biological tracer.84

Our tech revolution needs new battery technologies and various other physicochemical applications whose special characteristics require relatively rare metals like lithium (Li) and cobalt (Co) compared to iron, copper and aluminum. Cobalt provides a stability and high energy density that allows batteries to operate safely and for longer periods.85

In the brave new energy world of the not-so-distant future, battery storage is thought to make possible boundless clean energy and convenient technologies like fully electric vehicles and multiple hand-held devices, even though batteries are not particularly cost-effective relative to larger storage methods such as pumped hydro or compressed air. But for small devices, and even automobiles, it is essential.86

At present, the world’s energy-storage capacity is overwhelmingly dominated by pumped hydro, over 96%, followed distantly by electro-chemical (including batteries) at 1.5%, thermal also at 1.5% and electro-mechanical at only 0.8%. The pressure for new battery technologies is enormous.87

Within the geopolitical context is the problem of strategic stockpiling in the US including China, Russia and global economic and military powers.

No country may probably be more aware than the United States as to the strategic importance of cobalt to its defense and industrial power. It is not just about cell phones, electric vehicles, solar panels, etc. United States is not also unaware of the strategic importance of Congo in terms of the abundance of cobalt and other solid minerals including crude oil. This awareness can be traced to shortly after the end of the Second World War which account for its involvement in the political life of Congo since its independence from the colonial Belgium. But over the years, for reasons that lie outside the scope of this article, United States has been negligent about its attitude regarding strategic stockpiling of certain mineral resources.

Congressional Budget Office noted as far back as September 1982 that “cobalt is a metal used in U.S. aerospace and defense industries. At present it is not produced in the United States. It has been one of the metals purchased for the strategic stockpile. Vulnerability of the United States to shortfalls in the supply of cobalt and other minerals and materials is a concern of both the Congress and the Administration. Hearings have been held before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs to consider subsidizing domestic cobalt production.”88

The vulnerability of the United States to disruptions in the supply of imported materials considered essential to industrial production has been of concern to policymakers throughout the post-World War II era. Cobalt is a prime example of such a “strategic mineral.” Cobalt alloys are important to a number of U.S. industries, especially aerospace and defense, and short-run opportunities for substitution are limited. The bulk of the world’s supply of cobalt originates in central Africa (primarily Zaire and Zambia, which hold 64 percent of the world’s known cobalt reserves), a politically unstable region. At present, the United States produces no cobalt. Thus, aside from cobalt stockpiles and the recycling of used materials, the United States is completely dependent on imports. This gives rise to two kinds of vulnerability. The first is essentially military in nature: the possible need to wage a war in the absence of foreign supplies of cobalt. The second is economic: the effect on the economy of a disruption in foreign supply with an attendant sudden increase in price. The fourfold price increases during the late 1970s, and the worldwide scramble for cobalt supplies at that time, have given prominence to this second kind of vulnerability.89

The strategic stockpile, created to provide sufficient quantities of metals and materials for essential production during war, is below its current goals for many materials. In March 1981, the Administration initiated the purchase of 5.2 million pounds of cobalt for the stockpile—the first major purchase in 20 years. Taking a different approach, the Department of Defense announced in early 1982 that it was exploring the possibility of offering subsidies to U.S. mining companies to initiate production from otherwise uneconomic domestic cobalt ores. Congressional concern about possible cutoffs of cobalt imports prompted hearings before the Senate Banking Committee in October of 1981 focused on whether U.S. dependence on imports would justify subsidization of domestic production.90

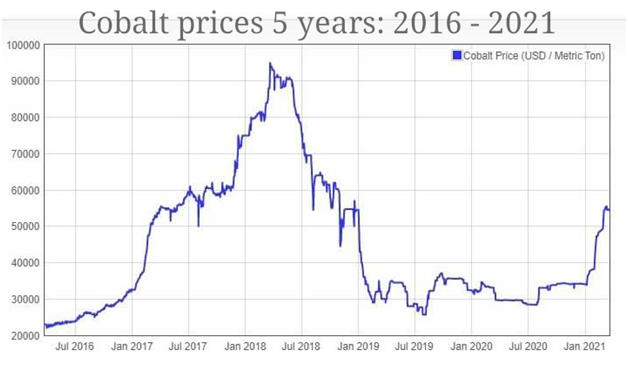

During the late 1970s, cobalt prices rose from $5.50 per pound to $25.00 per pound; spot prices were recorded as high as $50.00; and cobalt was in short supply. The tight market resulted from a combination of factors: military conflict in Zaire, expanding industrial economies, and a change in U.S. stockpile policy.91

The price increases had significant effects on U.S. cobalt demand, precipitating searches for substitutes, improved conservation, and increased recycling from scrap. Over the 1977-1979 period, these adjustments accounted for an estimated 19 percent reduction in what would otherwise have been the demand for cobalt. The experience was, for consumers of cobalt, a vivid illustration of the potential for future cobalt price swings and supply shortfalls. Accordingly, many U.S. industry efforts to identify cobalt substitutes continue, in spite of recent price declines. As of May 1982, cobalt’s price had fallen to $12.50 per pound.92

U.S. consumption of cobalt in 1980 totaled about 17 million pounds, divided among alloys for jet engines and stationary gas turbines, permanent magnets for electrical equipment, machinery, and nonmetallic applications.93

Demand for cobalt is extremely difficult to forecast because of the mineral’s specialized applications. Year-to-year fluctuations in cobalt use are often dramatic. Given the high levels of activity expected in a number of industrial sectors that traditionally use cobalt, in particular aerospace and electronics, estimates of about 30 million pounds of cobalt use by 1990 appear reasonable, although the further development of cobalt substitutes could appreciably reduce this estimate. More importantly, the development of substitutes would reduce U.S. vulnerability to supply shortfalls.94

U.S. involvement in a direct military conflict could conceivably result in a shutoff of cobalt supplies to the United States. Thus some contingency plan that will supply cobalt for defense purposes appears warranted.95 Concentration ofthe world’s cobalt reserves in central Africa suggests that the threat of price increases and supply disruptions will continue throughout this decade.96Significant adjustment to a supply disruption is possible. Private inventories and in-pipeline supplies would provide an initial buffer. Suppliers of cobalt unaffected by the political disturbance could also be expected to increase their output. Scrap recovery would also increase.97

Substitution possibilities exist for a number of cobalt uses, and some have already been applied; the price rises attending a shortfall should accelerate their introduction. These adjustments and others appear to be sufficient to limit the effects of supply shortfalls largely to the payment of higher prices for cobalt and its substitutes. The financial costs of higher cobalt prices, although potentially devastating to particular cobalt users,appear inconsequential to the economy as a whole. Although severeshortfalls could generate tenfold price increases, these would amount to less than $2 billion in a $3 trillion economy, and the value of imports would be less than 5 percent of the costs of U.S. petroleum imports from OPEC countries in 1981.98

The Strategic and Critical Materials Stockpiling Act of 1946 requires that stockpiling of cobalt be done in sufficient quantities to provide supplies necessary for military, industrial, and essential civilian needs for the fighting of a three-year war. Executive agencies have translated this directive into a stockpile goal for cobalt of 85.4 million pounds, about one-half of which has been stockpiled so far.99

As previously noted, the costs of shortfalls to the United States are likely to be quite limited in peacetime. Nonetheless, the possibility of a cutoff of cobalt supplies in wartime justifies some contingency plan for defense purposes. The strategic stockpile, given current cobalt prices, is probably the least expensive solution. The government recently purchased cobalt at $15 per pound for the stockpile, a price significantly below the estimated $25 cost for domestically produced ores. Moreover, the protection afforded by stockpiled cobalt extends beyond the mandatory threeyears, since domestic ore bodies could be brought on-line within that timeand greatly extend the years of protection afforded by the stockpile.100

Finally, the recent development of significant substitutes for cobalt suggests that the stockpile goal may be in need of reevaluation. Any reduction in the goal would reduce the cost of the stockpile. A number of alternatives to the present policy are conceivable:

- A separate “economic stockpile” that could be drawn upon to moderate cobalt price swings;

- Subsidies to induce domestic ore production;

- Increased federal funding for research and development to expand the supply of cobalt and its substitutes;

- Expanded access to public lands for the location and development of domestic ore; and

- Accelerated development of ocean mining to tap the vast stores of cobalt contained in marine manganese nodules.

Any of these alternatives would afford a certain degree of protection against supply hazards—but each would entail some cost.101

An economic stockpile, designed to moderate the impact of cobalt price increases to U.S. users of cobalt, would be an expensive form of protection in relation to the limited nature of the costs to the United States associated with such increases. The same would be true of subsidies for domestic ore production.102

Increased research and development efforts could enable U.S. consumers of cobalt to substitute other metals, and also expand cobalt supply possibilities. Judgments about the appropriate level for research and development funding are always difficult to assess. In any event, it is noteworthy that substitution of other metals helped to mitigate the impact of the 1977-1979 price increases. It does not appear that cobalt’s strategic importance should be a major consideration in decisions relating to public lands or accelerated ocean mineral development.103

Concern about U.S. reliance on foreign supplies of cobalt is part of a more far-reaching anxiety over several dozen minerals—including chromium, platinum, manganese, and bauxite—that are considered essential to U.S. production of goods and services but not produced domestically in quantities adequate to meet U.S. needs. They are termed “strategic and critical” minerals because of the precariousness of their availability and their critical rolein U.S. manufacturing. Because U.S. industry, in particular jet engine manufacturers, depends so heavily on imported cobalt, and because the world’s reserves are concentrated in a very few politically unstable nations, concern has arisen over possible disruptions in supply. Military strategists assume the worst case in which allair and shipping lanes would be blocked and no cobalt would reach American shores. There is also growing concern about nonmilitary cutoffs of cobaltsupplies by cartel actions or political upheavals in major producing nations. Many observers also see the possibility of episodic rises in the price of cobalt such as occurred in the late 1970s.104

The above were the kind of thinking and policy considerations at that time. It is, however, interesting to note that throughout this 50-page document, nowhere was China mentioned – ostensibly because China has not yet emerged as both a global superpower and competitor for strategic and critical mineral resources of any known description.

But the situation has changed over the last two decades with the gradual emergence of China both as an economic and military superpower that now effectively rivaled the United States.

In 2019, the nickel-copper Eagle Mine in Michigan produced cobalt-bearing nickel concentrate. In Missouri, a company built a flotation plant and produced nickel-copper-cobalt concentrate from historic mine tailings. Most U.S. cobalt supply comprised imports and secondary (scrap) materials. Approximately six companies in the United States produced cobalt chemicals. About 46% of the cobalt consumed in the United States was used in super-alloys, mainly in aircraft gas turbine engines; 9% in cemented carbides for cutting and wear-resistant applications; 14% in various other metallic applications; and 31% in a variety of chemical applications. The total estimated value of cobalt consumed in 2019 was $400 million105

Congo (Kinshasa) continued to be the world’s leading source of mined cobalt, supplying approximately 70% of world cobalt mine production. With the exception of production in Morocco and artisanally mined cobalt in Congo (Kinshasa), most cobalt is mined as a byproduct of copper or nickel. China was the world’s leading producer of refined cobalt, most of which it produced from partially refined cobalt imported from Congo (Kinshasa). China was the world’s leading consumer of cobalt, with more than 80% of its consumption being used by the rechargeable battery industry.106

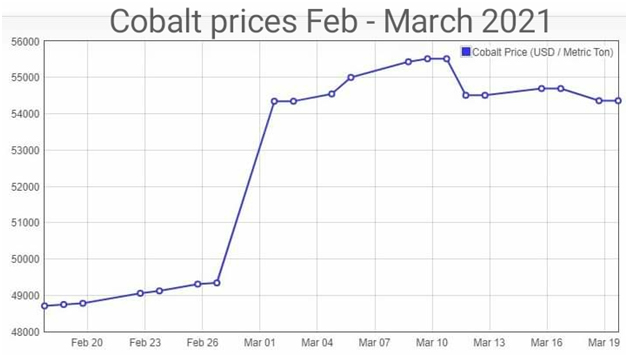

During the first 7 months of 2019, cobalt prices generally trended downward, which analysts attributed to oversupply and consumer destocking and deferral of purchases. In early August, a Switzerland-based producer and marketer of commodities announced that, owing to low cobalt prices, it planned to place its world-leading cobalt mine on care-and-maintenance status by year end 2019. Following the announcement, cobalt prices increased, then stabilized.107

Reserves for multiple countries were revised based on industry reports.

Mine production Reserves

2018 2019

United States 490 500 55,000

Australia 4,880 5,100 1,200,000

Canada 3,520 3,000 230,000

China 2,000 2,000 80,000

Congo (Kinshasa) 104,000 100,000 3,600,000

Cuba 3,500 3,500 500,000

Madagascar 3,300 3,300 120,000

Morocco 2,100 2,100 18,000

New Caledonia 2,100 1,600 —

Papua New Guinea 3,280 3,100 56,000

Philippines 4,600 4,600 260,000

Russia 6,100 6,100 250,000

South Africa 2,300 2,400 50,000

Other countries 5,540 5,700 570,000

World total (rounded) 148,000 140,000 7,000,000

Identified cobalt resources of the United States are estimated to be about 1 million tons. Most of these resources are in Minnesota, but other important occurrences are in Alaska, California, Idaho, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Oregon, and Pennsylvania. With the exception of resources in Idaho and Missouri, any future cobalt production from these deposits would be as a byproduct of another metal. Identified world terrestrial cobalt resources are about 25 million tons. The vast majority of these resources are in sediment-hosted stratiform copper deposits in Congo (Kinshasa) and Zambia; nickel-bearing laterite deposits in Australia and nearby island countries and Cuba; and magmatic nickel-copper sulfide deposits hosted in mafic and ultramafic rocks in Australia, Canada, Russia, and the United States. More than 120 million tons of cobalt resources have been identified in manganese nodules and crusts on the floor of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans.108

Substitutes: Depending on the application, substitution for cobalt could result in a loss in product performance or an increase in cost. The cobalt contents of lithium-ion batteries, the leading global use for cobalt, are expected to be reduced rather than eliminated; nickel contents of lithium-ion batteries will increase as cobalt contents decrease. Potential substitutes in other applications include barium or strontium ferrites, neodymium-iron-boron, or nickel-iron alloys in magnets; cerium, iron, lead, manganese, or vanadium in paints; cobalt-iron-copper or iron-copper in diamond tools; copper-iron-manganese for curing unsaturated polyester resins; iron, iron-cobalt-nickel, nickel, cermets, or ceramics in cutting and wear-resistant materials; nickel-based alloys or ceramics in jet engines; nickel in petroleum catalysts; rhodium in hydroformylation catalysts; and titanium-based alloys in prosthetics.109