By Alexander Ekemenah, Chief Analyst, NEXTMONEY

Introduction

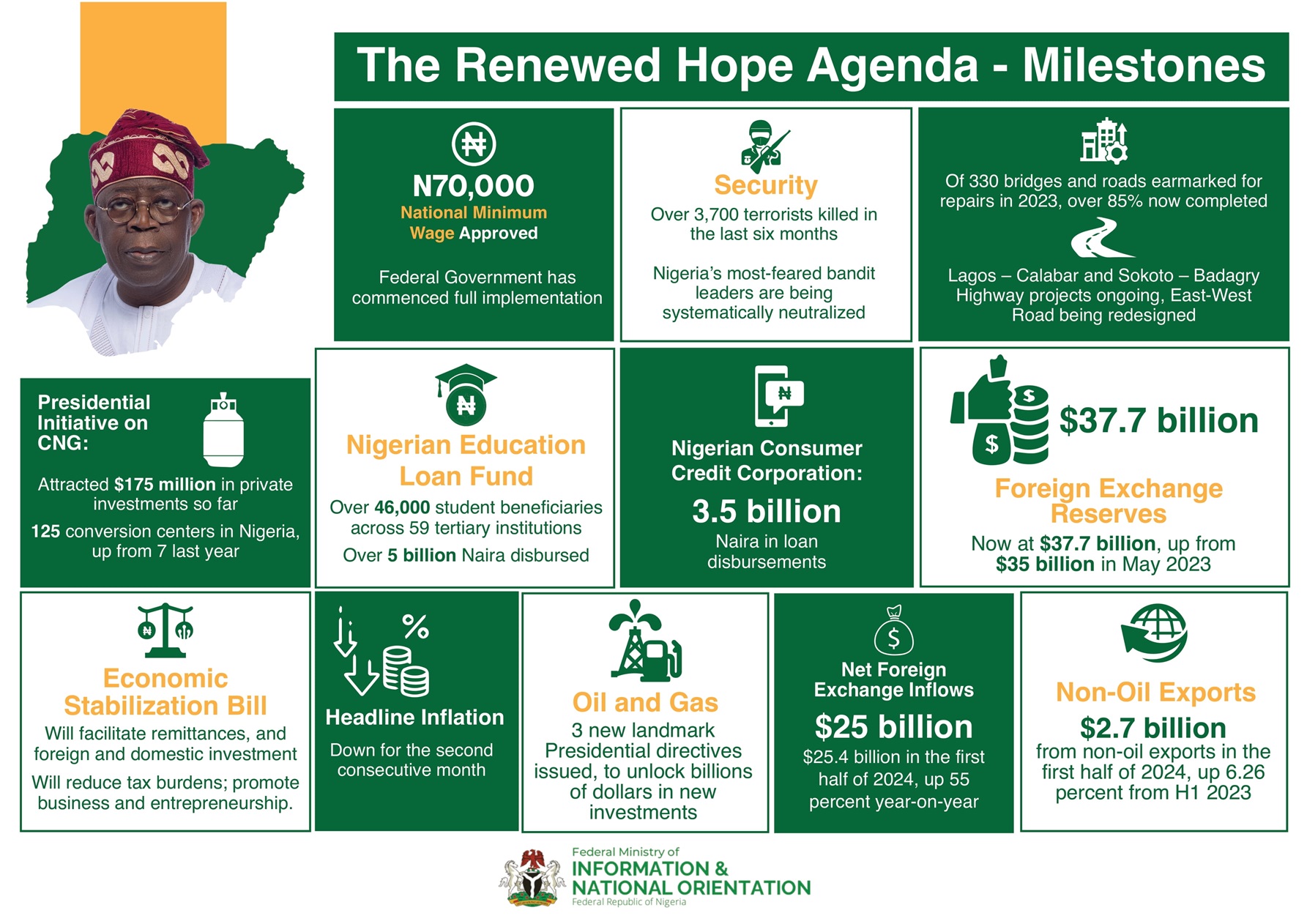

For many African media houses, there is high possibility of the ongoing Ethiopian-Tigrayan armed conflict escaping adequate or critical attention. This is because many individual African countries are faced with their own specific problems of the character of existential challenges that often preclude deep interest or involvement in other countries’ internal problems of their own makings – except for mischief purpose. For instance, Nigeria is faced with a high intensity insecurity framed by raging insurgency, banditry, kidnapping and herdsmen killings in the northern part of the country including increasing killings in the southeastern part of the country. Additionally, Nigeria is gradually being enveloped by politics of 2023 elections as presidential contestants are now emerging from all nooks and crannies of the country. As a result of these unfolding events, little is heard of the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict in the Nigerian media.

But the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict which has been raging for almost a year now is an additional pressure on the continent that has already been weighed down or buffeted by myriad of problems ranging from growing insecurity in many African countries, economic crisis, poor governance, including ethno-religious conflicts. Indeed, the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict involved these four already denominated problems including humanitarian crisis caused by the conflict – from both sides of the conflict. Additionally, the conflict has spanned and spawned the entire region (including the superjacent region of the Gulf of Aden) drawing other neighbouring countries into the vortex of the conflict including global superpowers such as the United States, China, Russia and others.

Statement of the Problem

There are inescapable four sets of identifiable problems as the main causative factors of the conflict and which also serve as the main drivers of the conflict.

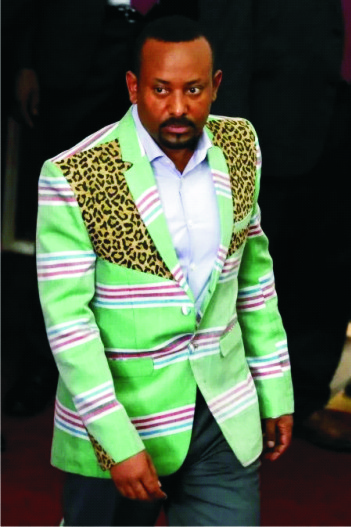

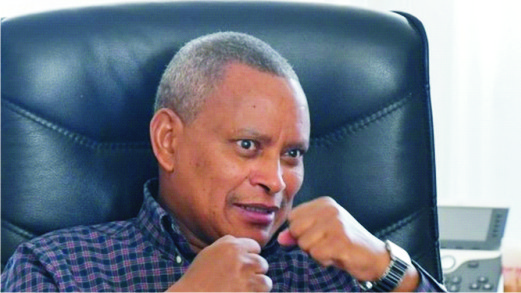

The first is the 2018 Ethiopian general election which saw the emergence of the young but brash Abiy Ahmed as the Ethiopian Prime Minister who came with a loaded suitcase of political reforms that has been identified as part of the reasons for the outburst of the conflict especially igniting rebellion on the part of Tigray, a regional minority that has hitherto served as the political elite of Ethiopia prior to the 2018 general election. On the side of Tigray is Debretsion Gebremichael as the leader of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) – the main arrowhead of the Tigrayan opposition forces against Ethiopia – who had hitherto held high-profile positions in Addis Ababa before falling out with the government led by Abiy Ahmed. Things did not seem to have gone down well with Tigrayans who felt upstaged from their hitherto sinecure or hegemonic political position. This is the immediate cause of the conflict.

The second is the ongoing construction of the huge Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile which has drawn in countries like Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea and Somalia into the conflict mostly on the side of Ethiopia (though with their individual differences) which conveys a kind picture of grand conspiracy against Tigray for varied reasons. All countries with varied degree of interests in the electricity project, including the United States, have been playing politics with the project – indeed playing one country against the other especially Egypt and Ethiopia. While the construction of the dam is not a direct cause of the conflict, it has, however, become source of friction between Ethiopia on the one hand and the other countries on the other.

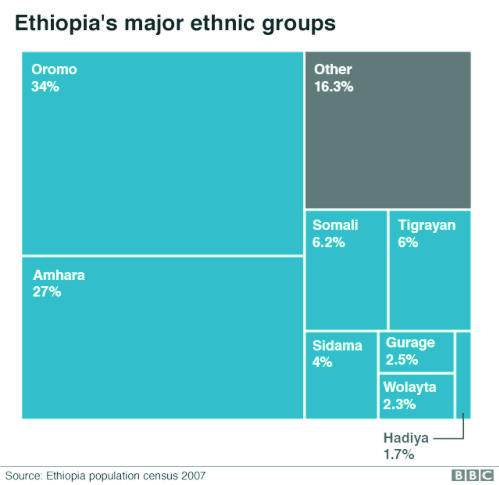

There is also the ethnic dimension to the conflict. Ethiopia can be seen to be suffering from the inability to manage its ethnic diversity. This is perhaps the major problem with Ethiopia. Ethiopia originally has about 80 ethnic groups but grouped into 10 regions (excluding Eritrea that has broken away as far back as 2011). The Oromo ethnic group is the largest followed by Amharas and lastly by the Tigrayans, among others. Interestingly, the Amharas, the second largest group has been the historic rulers of Ethiopia until the Tigrayans took over in the early 90s after the Mariam Haile Mengistu’s Marxist Derg regime was pursued out of Addis Ababa. The rivalry between the three major ethnic groups and struggle for domination or hegemonic power in Addis Ababa (similar to the situation in Nigeria) must be factored into the overall analysis of this epochal crisis rocking the Ethiopian State that is already causing jitters about the grave threat to its very existence. Ethiopia stands the risk of disappearing as a nation-state the way it is going in the final analysis.

Ethiopia as a regional hegemon is being seen to be gradually whittling down in its hegemonic powers not only by internal strife but also by covert or overt hostility from its neighbours. Eritrea has already bolted away from the “union” as far back as 1991 even though it is currently supporting Ethiopia in the war against Tigray for geostrategic reasons. Those reasons will be disambiguated below. If Tigray succeeds in the years to come, despite the current excruciating pains, then Ethiopia can no longer be “Ethiopia” as we know it today. It would then remain a shell of its former self and nobody can be assured of the sustainability of the remnant of the “Ethiopian union” in this context based on the reality of ethnic cleavages that serve as dysfunctioning mechanism in the African state structural formations.

The fact these fears are being raised is an ominous sign that all may not really be well with Ethiopia contrary to impression created by Ethiopian government propaganda and those who believe in such propaganda. It can no longer be denied that the nuts and bolts that have hitherto held the country together have been wittingly or unwittingly loosened over the years by factors and forces beyond control.

Another dimension is the ferocious rivalry between two former comrades: Abiy Ahmed of Ethiopia and Debretsion Grebemichael of Tigray – a rivalry escalated by interference of the autocratic Eritrean leader, Isaias Afwerki. There is a sense in which it can be argued that the conflict is simply a fight among the three men. But such a reductionist methodology will not capture all the nuances of the conflict. The three men are simply representatives of aggregate forces that are involved in this epochal conflict including external forces. The three leaders, however, represent different schools of ideologies and hegemonic ambitions which have largely prevented mutual consensus on how to de-escalate the growing tensions among the three countries. In the Western media, Abiy Ahmed has been largely portrayed and presented as Mr. Nice Guy but who in reality is a new political breed or typology. His so-called sweeping political reforms (but anti-federalist reforms) are evidently not well calibrated enough. They essentially failed to take into consideration the political and ethnic reality of Ethiopia especially the sensitivity of the Tigrayans. Riding on the crest-waves of this rightwing populist reforms, Abiy Ahmed did not probably consider the effects of these reforms in advance before setting them into motion. And with his evident hubris and characteristic brashness, Abiy Ahmed has crossed the point of no return in his push for these reforms and the path to self-destruction.

It is doubtful if Abiy Ahmed could continue to sustain the image of Mr. Nice Guy when all the facts are laid bare and objectively viewed. While there is also nothing special about the Tigrayans or their political sensitivities, the fact remains that they are the elite just dethroned from power through the 2018 general elections and they are still smarting or squirming from the crushing defeat.

The Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict is the direct product of imposing reforms from the top without bothering to carry the grass-root along. The Abiy Ahmed-led reforms are top-down that eventually met resistance from below especially from Tigray.

Finally, the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict once again exposes and demonstrates the abysmal failure of African Union, the East African Community and other critical stakeholders in conflict prevention and alternative dispute resolutions. It is this strange failure that has helped to escalate the stakes in the conflict. In virtually all contemporary conflicts in Africa, armed conflict is usually the first step causing destruction of lives and properties and AU has demonstrated its utter failure or helplessness to prevent armed conflicts in the first instance. Political dialogue only follows as “medicine after death”, after wholesale destructions of lives and properties have taken place. The ineffectiveness of the AU comes with enormous collateral damage that is hard to quantify or qualify. Injured feelings or wounded prides linger for ages. What really is AU for when it cannot prevent conflicts from taking place in the first instance – instead of waiting for the eruption of the conflicts before embarking on knee-jerk reactions? AU has demonstrated times without number that it has become more of a talking shop than a proactive body that take initiatives to forestall crises or conflicts. Its horizon-scanning ability is zero, to say the least.

And the Conflict Begins

The Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict began like any other conflict elsewhere when “the falcons can no longer hear the falconer” or when the “centre can no longer hold” for reasons that are argued this way or that way in favour of one party or the other.

The conflict is rooted in the historical dynamics of Ethiopian politics itself. It is situated within the general context of confluence of factors that have been evolving over the years without anybody designating them as dangerous enough to cause conflict in the long run. They remain largely unattended to over the years until they became monstrous enough to start tearing apart the fabric of the social and political order. There is a sense in which it can be argued that Ethiopian State has suffered more from political instability and authoritarianism than from any other factor. The encountered economic crisis over the years was the direct product of this political instability-cum-authoritarianism.

Thus an historical perspective must be adopted in critically interrogating the ongoing conflict – without which it is not possible to understand the background to the crisis.

Ethiopia was ruled under a single dynasty, the House of Solomon, from antiquity until the 1970s. One of just two African nations to avoid European colonization—Liberia being the other—it was nonetheless occupied by Italy in the 1930s, forcing Emperor Haile Selassie to flee. He was only able to return after British and Ethiopian forces expelled the Italian army in the course of World War II.1

In 1974, a communist military junta known as the Derg, or “committee,” overthrew Haile Selassie, whose rule had been undermined by a failure to address an ongoing famine. During the resulting civil war, the military regime violently persecuted its rivals, real and suspected; a particularly deadly campaign, begun in 1976, was known as Qey Shibir, or the Red Terror. Tens of thousands of people died as a direct result of state violence, and hundreds of thousands more died in the 1983–85 famine.2

In 1989, several opposition groups came together to form the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), led by Meles Zenawi Asres of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). The government (Mengistu-led Marxist regime) had been weakened after losing the support of the Soviet Union, itself on the verge of collapse, and the EPRDF forces defeated the Derg in 1991.3

Meles led the country for more than two decades, during which he consolidated his party’s hold on power. He introduced ethnic federalism, or the reorganization of regional government along ethnic lines, and he oversaw an era of massive investment, both public and private, to which many observers attributed the country’s subsequent growth. Critics, however, say Meles was a strongman who suppressed dissent and favored the country’s Tigrayan minority. Following Meles’s death in 2012, his deputy prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, took over.4

The almost three decade-long rule by Zenawi and the introduction of the so-called ethnic federalism (to consolidate the rule by Tigray) was what the sole purpose of Abiy Ahmed-orchestrated political reforms seek to dismantle because it marginalized the Oromos and other ethnic groups from the loci of the State or centre of power in Addis Ababa. Thus the Zenawi-led ethnic federalism and the Abiy Ahmed-led political reforms are the remote catalysts for the current conflict.

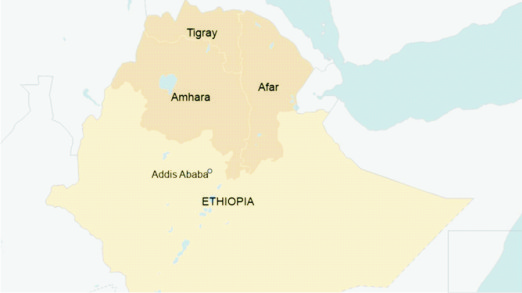

Tigray is one of ten regional states located in northern Ethiopia, sharing a border with Eritrea to the north and Sudan to the west. Prior to current Abiy’s ascension to power in 2018, the state dominated politics at the national level, with most of Ethiopia’s ruling coalition comprised of leaders from the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).5

In 2018, Abiy’s national election win signaled a transfer of power from the decades-long rule of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). While in power, the TPLF had implemented a series of political reforms that marginalized other ethnic groups and consolidated the central government. Abiy’s ascent to power was buttressed by his visions of an ethnically harmonious, unified Ethiopia and initially appeared to be a critical change of course from the divisive policies of the TPLF-dominated ruling coalition. However, internal political friction between the TPLF and the government intensified during Abiy’s initial tenure, as the internationally lauded liberal reforms enacted by Abiy’s government marginalized the TPLF.6

In September 2020, following multiple delays in parliamentary elections and the extension of Abiy’s presidential term, the Tigray State Council defied the federal government and held regional elections, in which TPLF candidates won a majority of seats. In advance of the elections, Tigray leaders warned that intervention from the federal government would be considered a “declaration of war.” Abiy condemned the Tigray regional elections, accused the TPLF of attacking a military camp and looting federal military assets, and then declared a six-month state of emergency and swiftly deployed troops to Mekelle, the capital of Tigray, in an offensive ostensibly targeting rebel TPLF leaders.7

Abiy first framed the Ethiopian government’s Mekelle offensive – which began in November 2020 – as a targeted operation against regional leaders in Tigray after failed cease-fire negotiations. However, troops began committing widespread atrocities from the start of the offensive against those they identified as Tigray civilians. A communications blackout near the beginning of the conflict shuttered coverage of the offensive, but the media has since been able to paint a fuller picture of the extent of the atrocities that have been committed in Tigray through firsthand witness accounts, video clips, and other testimony.8

Even as the offensive quickly escalated into a much broader war, with civilians facing the brunt of the violence, Abiy’s government rejected calls for mediation. Eritrean forces also joined the side of the Ethiopian government early in the conflict, and after months of denying their presence, in spring 2021 Abiy admitted that Eritrean troops were in Tigray. The TPLF and Eritrea have a history of hostile relations: Eritrea fought a brutal, decade-long war of independence against Ethiopia in the 1980s and 1990s, when the TPLF held power in Ethiopia’s ruling coalition. Eritrean troops have shown no sign of leaving, despite international pressure.9

The United States has characterized the conflict as ethnic cleansing against Tigrayans, and harrowing reports have documented the prevalence of mass atrocities in the conflict, including troops and members of militias perpetrating rape and sexual violence against women and girls in particular. These reports have raised the question of accountability for serious rights violations. In March 2021, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights announced a joint probe with the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) to investigate alleged serious abuses and rights violations in Tigray, although the impartiality of the joint probe has been drawn into question. Proposed efforts to call for an end to the violence from the UN Security Council have failed as a result of Chinese and Russian vetoes, countries that maintain the conflict to be an internal Ethiopian affair.10

For decades, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) was the dominant party in Ethiopia’s ruling coalition, but Abiy’s ascent in 2018 heralded a recalibration of power. This change was an attempt to address domestic dissatisfaction with political repression, concerns about access to resources and opportunity, and the perception that an ethnic minority held outsized power and influence. (Tigrayans constitute roughly 6 percent of Ethiopia’s population.)11

But the TPLF felt threatened by the new government’s personnel and policy choices, and it declined to join the successor party to the old ruling coalition. In September, it chose to proceed with its own regional elections in defiance of a federal decision to postpone elections due in part to the COVID-19 crisis. A reported TPLF attack on federal forces stationed in the region was the immediate trigger for the conflict, but it was clear that both sides were preparing for confrontation for some time.12

The conflict was not so much as a result of the elections of 2018 but as well as the cumulative result of the tension that has been building up for many years before the elections. From Halie Selassie’s monarchical government to the Mengistu’s Marxist regime and to the Meles Zenawi-led parliamentary government, the Ethiopian State has largely functioned as an instrument of political dictatorship of one ethnic group or the other to the pains and sufferings of other ethnic groups whether they in the majority or not. This last point was the case during the reign of Meles Zenawi for almost thirty years. Zenawi is a Tigrayan and succeeded in consolidating the rule of Tigray over the rest of other ethnic groups. Even after Zenawi died in 2012 and with Haliemariam Desalegn taking over, there was no visible recalibration of power in Addis Ababa. It is just a question of time before the pot of rebellion will boil over.

That time came with the 2018 Ethiopian general election. The 2018 election result was a clear reaction against this minority rule of the Tigrayans. The election saw the landslide victory of Abiy Ahmed, an Oromo, as the Prime Minister. The election result with the victory and emergence of Abiy Ahmed as the Prime Minister is the final straw that broke the camel’s back of the internal crisis within Ethiopia after the splitting away of Eritrea in 1991. The over-centralization of power in Addis Ababa and the corollary lack of adequate regional autonomy are inevitably bound to cause a conflict at one point or the other – even with the so-called ethnic federalism bequeathed as a legacy from Zenawi’s government. The latter struggle for power by the regional blocs and political warlords including the political reforms initiated by Abiy Ahmed are a manifestation of these conflicts of which seeds have already been planted in the Ethiopian State or the so-called “federal” structure.

Of course, the election result blew open the hitherto undeclared rivalry between the two main gladiators: Abiy Ahmed of Oromo ethnic group and Debretsion Gebremichael of Tigray. Debretsion Gebremichael and his core supporters lost out in the power equation through the 2018 election. A new coalition and configuration of power emerged in Addis Ababa as a result of the victory of Abiy Ahmed in the 2018 general elections. The fallout between the two gladiators was worsened by Abiy Ahmed-led sweeping political reforms which are perceived to have further emasculated the Debretsion Gebremichael and the Tigrayan political elite.

The first shot or strike was fired by Ethiopia when Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed ordered troops into Tigray to quarantine or uproot the Tigray People Liberation Front (TPLF) for what Abiy Ahmed claimed to a provocation from Tigray when it allegedly attacked Army camps based in Tigray and looted their assets which was followed by declaration of state of emergency or force majeure and deployment of troops to Mekelle, the capital of Tigray.

A conflict between the government of Ethiopia and forces in its northern Tigray region has [therefore] thrown the country into turmoil. Fighting has been going on since November 2020, destabilising the populous country in the Horn of Africa, leaving thousands of people dead with 350,000 others living in famine conditions. Eritrean soldiers are also fighting in Tigray for the Ethiopian the government. All sides have been accused of atrocities.13

A power struggle, an election and a push for political reform are among several factors that led to the crisis. The conflict started on 4 November [2020], when Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed ordered a military offensive against regional forces in Tigray. He said he did so in response to an attack on a military base housing government troops there. The escalation came after months of feuding between Mr. Abiy’s government and leaders of Tigray’s dominant political party.14

For almost three decades, the party was at the centre of power, before it was sidelined by Mr. Abiy, who took office in 2018 after anti-government protests. Mr. Abiy pursued reforms, but when Tigray resisted, the political crisis erupted into war.15

The roots of this crisis can be traced to Ethiopia’s system of government. Since 1994, Ethiopia has had a federal system in which different ethnic groups control the affairs of 10 regions. Remember that powerful party from Tigray? Well, this party – the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) – was influential in setting up this system. It was the leader of a four-party coalition that governed Ethiopia from 1991, when a military regime was ousted from power.16

Under the coalition, Ethiopia became more prosperous and stable, but concerns were routinely raised about human rights and the level of democracy. Eventually, discontent morphed into protest, leading to a government reshuffle that saw Mr. Abiy appointed prime minister. Mr. Abiy liberalised politics, set up a new party (the Prosperity Party), and removed key Tigrayan government leaders accused of corruption and repression. Meanwhile, Mr. Abiy ended a long-standing territorial dispute with neighbouring Eritrea, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize in 2019.17

These moves won Mr. Abiy popular acclaim, but caused unease among critics in Tigray. Tigray’s leaders saw Mr. Abiy’s reforms as an attempt to centralise power and destroy Ethiopia’s federal system. The feud came to a head in September, when Tigray defied the central government to hold its own regional election. The central government, which had postponed national elections because of coronavirus, said it was illegal.18

The rift grew when the central government suspended funding for Tigray and cut ties with it in October. At the time, Tigray’s administration said this amounted to a “declaration of war”. Tensions increased, and the eventual catalyst was when Tigrayan forces were accused of attacking army bases to steal weapons. Mr. Abiy said Tigray had crossed a “red line”. “The federal government is therefore forced into a military confrontation,” he said.19

Ethiopia, Africa’s oldest independent country, has undergone sweeping changes since Mr. Abiy came to power. A member of the Oromo, Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group, Mr. Abiy made appeals to political reform, unity and reconciliation in his first speech as prime minister. His agenda was spurred by the demands of protesters who felt Ethiopia’s political elite had obstructed a transition to democracy.20

According to the Africa Report: This war has been long in the making. For years, the cohesion within the ruling government coalition of the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) has withered, accentuated by the widespread disturbances during 2015-2018 instigated by the Qeerroo (Oromo) followed by the Fano (Amhara) youth protest movements.21

The youth protested against government abuse and maladministration, as well as TPLF dominance within the EPRDF. The Qeerroo demanded an ‘Oromo First’ policy, that the Oromo should exercise self-rule in Oromia and be the dominating force at the federal level, due to their demographic size.22 The internal power-struggle culminated with the ascent of Abiy to the helm in April 2018. Representing the Oromo faction of the coalition with the support of the Amhara party, Abiy’s rise undercut the longstanding Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) dominance of the EPRDF.23 In December 2019, initial tensions between the factions of Abiy’s EPRDF morphed to open hostility when he dissolved the coalition and crafted the Prosperity Party from its ashes.24

The TPLF leadership declared the dissolving of the EPRDF as illegal and regrouped in Tigray, where they started to design their own development policies and political visions of a Tigray “de facto state” with a looser relationship with the federal government. Subsequent attempts by, inter alia, religious leaders to pacify the increasing tensions failed.25

The decisive breach of relations between the federal government and Tigray’s rulers began with Addis Ababa’s decision to postpone the 2020 general elections due to the pandemic. TPLF, believing it was because Abiy feared losing at the polls, characterized the postponement beyond government term limits unconstitutional.26 The TPLF decided to proceed with elections in Tigray, which the federal government condemned as unconstitutional. Addis warned of sanctions and possible intervention if the regional poll went ahead. Tigray did not budge, however.27

During the 9 September elections,[…] it was clear that for them, this was not an ‘ordinary election,’ but a referendum on their security and self-determination. In this respect, it was a plebiscite on TPLF’s role as the protector of Tigrayan people and the spirit of woyane (Tigrinya for ‘rebellion’)—the resistance against centralized rule and outsized influence on Tigray.28 Even local opposition members threw their support to the TPLF. “As the situation is, even I will vote for the TPLF. They are the only one who can offer us protection against the threats from the federal government. The way PM Abiy Ahmed has handled the issue has paradoxically made him the best campaign manager TPLF could have imagined.”29

In the aftermath of a TPLF landslide win, both governments denounced each other as unconstitutional, leading to the formal breach of political relations. From there, it was just a matter of time before the political conflict would explode into armed confrontation.30

The above is the general contour of events that finally led to the conflict (war) breaking out between the two parties (Ethiopia and Tigray). One thing led to the other in a chain reaction, from the dissolution of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) to the formation of Prosperity Party by Abiy Ahmed Government, the postponement of the 2020 election followed by the defiance of Tigray People’s Liberation Force and insistence in holding the election at all cost, the holding of the regional election in which the TPLF emerged victorious, the declaration of the election as unconstitutional by Abiy Ahmed Government, the declaration of state of emergency in Tigray by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, the sending of troops to Mekelle by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, the intervention of Eritrea on behalf of Ethiopia, the counter-offensive by Tigray and the push into Afar and Amhara regions – formed the body of events that characterized this conflict.

From the various sources quoted above, one can discern subtle narratives and counter-narratives creating a confused picture. But what is certain is that Tigray’s revolt was not based on any identifiable nationalism but on what it felt or perceived as political exclusion or marginalization from Abiy Ahmed’s government. A careful reading of the propaganda from Tigray would also show that it is not agitating for an independent sovereign state per se – even when that may turn out to be the ultimate goal at the end of the day. But at least that evolutionary point has not been reached. Tigray can be seen to still be fighting for that “ethnic federalism” bequeathed by Meles Zenawi.

The war began last year [November 2020], after months of feuding between Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government and leaders of the TPLF, the main political party in the Tigray region. The prime minister sent troops to Tigray to overthrow the regional government after accusing the TPLF of seizing military camps. The government has designated the TPLF as a terrorist group, while it says it is the legitimate government of Tigray. Thousands of people are thought to have been killed and millions have been forced from their homes, with some fleeing into Sudan. Both sides have been accused of committing atrocities, including rape and mass civilian killings.31

Thousands have been reported killed in clashes in northern Ethiopia, as fighting between the military and Tigray rebels continue. The conflict has been raging for 10 months, pushing hundreds of thousands of people into conditions of famine. The rebel forces said on Sunday that they had killed 3,073 “enemy forces”, with 4,473 injured. It comes after the military said it had killed more than 5,600 rebels, without specifying a timeframe. Senior army general Bacha Debele said a further 2,300 rebels were wounded and 2,000 captured.32

It is hard to verify figures from either side due to a communications blackout in the region. The rebels said their figures were from the Afar and Amhara regions which border Tigray, adding that they had seized military tanks and weapons. Berhane Gebrekristos, Ethiopia’s former ambassador to the US, and now a supporter of the rebel Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) group, described the government’s claims as “false and laughable”. “The last five or six days, there were major military offensives by the TPLF in the two regions. In Afar and in the Amhara region, they [the Ethiopian military] lost eight divisions,” he said. He accused the military of trying to come up with “fake information” to give a morale boost to its troops. Lt Gen Debele had earlier accused the TPLF of trying to break up Ethiopia. He said one rebel division had tried to gain control of the town Humera in Tigray, but had been “completely decimated”.33

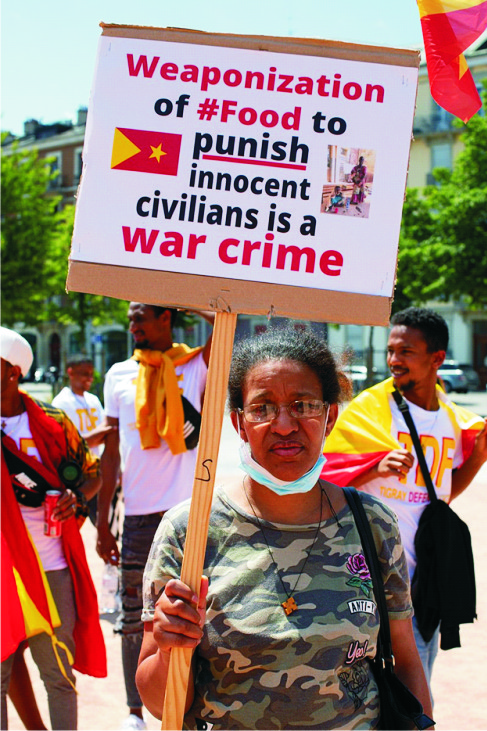

The UN accused the government of effectively blockading aid supplies to Tigray, warning that millions of lives were being put at risk. The UN estimates that 5.2 million people need urgent assistance if “the world’s worst famine situation in decades” is to be averted. It previously said some 400,000 were already living in famine-like conditions. But the Ethiopian government said 500 trucks with aid had entered the region, including 152 in the past two days. The number of security checkpoints had also been reduced, it said. The UN had complained that not a single truck had reached Tigray since 22 August, while 100 per day were needed.34

Evidently, the conflict came to a head when Abiy Ahmed ordered a military offensive against regional forces in Tigray for the perceived political belligerency of Debretsion Gebremichael-led Tigray regional government. When the conflict escalated with casualties on both sides, Ethiopia naturally resorted to weaponization or withdrawal of funding, foods and other humanitarian aids, including disruption of communication between Ethiopia and Tigray despite international outcries against these atrocities. Casualties in thousands of soldiers and civilians started mounting amidst accusation and counter-accusation of genocides and war crimes on both sides including Eritrea that entered the fray on the side of Ethiopia.

It is also evident that neither side sought political dialogue to resolve the disagreements in the first instance before resorting to armed conflict. This is rather unfortunate. Ethiopia thought that Tigray would be a quick walk-over in terms of military victory.

But things did not go the way expected by Ethiopia. Initially, Ethiopia was able to achieve the expected military victory by reaching Mekelle and taking over the town. But this was short-lived as Tigray launched a counter-attack that quickly sent Ethiopian troops out of Mekelle even with Eritrean forces already recruited like mercenary hirelings. Tigray launched a counter-offensive and pushed through to Amhara and Afar regions after re-taking Mekelle, the capital of Tigray, back from both Ethiopian and Eritrean forces. It was evident that Ethiopia was not in control of the dynamics and vectors of the war. It overestimated its own strength and underestimated the resilience of the Tigray People’s Liberation Force, the military arrowhead of the resistance to Ethiopian so-called federal over-lordship.

This was the obvious situation that compelled Ethiopia to call out on its citizens in late August 2021 for full-scale mobilization against Tigray. It is a sign of desperation on the part of Ethiopia, that even with the support of Eritrean forces, Ethiopia was fast losing the war to Tigray.

Ethiopia’s government on Tuesday summoned all capable citizens to war, urging them to join the country’s military to stop resurgent forces from the embattled Tigray region “once and for all.”35

The call to arms is an ominous sign that all of Ethiopia’s 110 million people are being drawn into a conflict that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, once declared would be over within weeks. The deadly fighting has now spread beyond Tigray into neighboring regions, and fracturing in Africa’s second most populous country could destabilize the entire Horn of Africa region.36 The prime minister’s summons chilled Tigrayans, even those outside Tigray, with the statement calling on all Ethiopians to be “the eyes and ears of the country in order to track down and expose spies and agents” of the Tigray forces.37

The expansion of fighting has alarmed some people of other ethnicities, such as the Amhara, who fear that the Tigray forces, now on the offensive, will take revenge. “We know the (Tigray People’s Liberation Front) is well-armed and the losers would again be the Amhara people,” Demissie Alemayehu, a U.S.-based professor who was born in the Amhara region, said shortly after the prime minister’s call to war. Without addressing Ethiopia’s root problems, including a constitution based on ethnic differences, he said, it will be “very difficult to talk about peace.” The deputy head of the Amhara regional government, Fenta Mandefro, asserted that hundreds of Amhara residents have already been killed.38

Fear of Ethiopia’s Disintegration

There are increasing concerns about Ethiopian unity as the conflict in the northern Tigray region escalates. It is a sign that the Tigray crisis is getting worse, but this is by no means the only fighting happening right now in Ethiopia. It is the second-most populous state in Africa with a history of ethnic tensions. In 1994, a new constitution was introduced which created a series of ethnically based regions meant to address the problem of an over-centralised state. Until 2018, the governing coalition was dominated by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and was criticised for crushing any dissent. After Abiy Ahmed – who comes from the largest ethnic group, the Oromo – became prime minister in 2018, he made a series of bold liberalising moves to end state repression. But this liberalisation was accompanied by a burst in ethnic nationalism, with different groups demanding more power and land. “You have a plethora of ethnic warfare,” says Rashid Abdi, a Nairobi-based expert on security in the Horn of Africa.39

Also jeopardising stability is the historic border dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia over fertile agricultural land in an area known as al-Fashaga. It is claimed by both states. The dispute has led to skirmishes between the two armies, amid the conflict in Tigray. Amhara regional authorities have over the past decade accused neighbouring Tigray of stoking the ethnic feud, which Tigrayans deny. Add to those, the flare up in a long-running dispute between Ethiopia’s Somali and Afar regions, dangerously close to the Djibouti border, and a growing insurgency against the Ethiopian military in the Oromia region, and it is easy to see why Ethiopia-watchers are worried. “Ethiopia goes through historical cycles of being robust and then precarious and it’s at one of those very, very precarious moments,” says Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation in the US.40

Some Ethiopian experts are now talking about state collapse as a real possibility. “There is no denying Ethiopia is at an existential crisis moment,” says Mr. Abdi. “How it is going to navigate this crisis in Tigray as well as multiple points of ethnic warfare nobody can be sure of, but it’s in serious crisis and there is a great risk of Ethiopia collapsing.”41

But an academic at Ethiopia’s University of Gondar, Menychle Meseret, said he did not believe that Ethiopia was on the brink of state collapse. “It is not even appropriate to have a discussion about it, in the first place. We have a functioning government that controls the country, except for Tigray,” he said. The crisis in Tigray had, in fact, strengthened “national cohesion” among other regions and ethnic groups, which have rallied behind the government and military, Mr. Menychle added.42

The Tigrayan forces have said they will not stop fighting until a number of conditions have been met by Mr. Abiy. This includes the end of the federal government’s blockade of Tigray and the withdrawal of all opposing troops – the Ethiopian army, forces from other Ethiopian regions and the Eritreans fighting alongside them. The blockade refers to the federal government’s shutdown of all electrical, financial and telecommunications services in Tigray since the Mekelle withdrawal in June. International organisations have also had difficulty getting much-needed aid through. Gen Tsadkan Gebretensae told the BBC’s Newshour programme that Tigrayan forces will continue to fight – including in Afar and Amhara regions – until their ceasefire conditions have been met. “All our military activities at this time are governed by two major objectives. One is to break up the blockade. The second is to force the government to accept our terms for a ceasefire and then look for political solutions.” The general added that the Tigrayans are not aiming to dominate Ethiopia politically as they have in the past. Instead they want Tigrayans to vote in a referendum for self-governance.43

Ethiopia’s minister for democratisation, Zadig Abraha, told the BBC the Tigrayan rebels had a false sense of power and would be driven out of every village of the region when the government ran out of patience. In a sign the conflict is drawing in yet more combatants, young Ethiopians gathered at a rally in the capital, Addis Ababa, last week, answering a call from regional leaders to join the fight against the Tigrayan rebels. The conflict has caused a massive humanitarian crisis. The United Nations’ children’s agency, Unicef, said that more than 100,000 children in Tigray could suffer life-threatening malnutrition in the next year, while half of the pregnant and breastfeeding women screened in the region are acutely malnourished. Food experts say 400,000 people in Tigray are experiencing “catastrophic levels of hunger”. All aid routes into Tigray are blocked except for one road from Afar region where food convoys have recently been attacked, reportedly by pro-government militias. The Tigrayan forces say they are hoping to force open a new aid corridor via Sudan by defeating the Ethiopian army and Amhara troops stationed there.44

As Ethiopia’s civil war spreads out of Tigray, the government of Africa’s second-most populous nation is under increasing threat.45

The northern region’s leaders are forming alliances with groups including a rebel army from the Oromo, the country’s biggest ethnic group — an ominous historical sign for Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front overthrew the communist Derg regime in 1991 and dominated Ethiopian politics for the next 27 years. This wasn’t what Abiy envisaged when he sent his army into Tigray 10 months ago. He promised a swift conflict in retaliation for an assault on an army base. But the TPLF has since regained control of the province and its forces are pushing into neighboring Amhara and Afar.46

While their end-game is unclear, a repeat of 1991 seems unlikely. “They want a transitional government in Addis Ababa,” said Connor Vasey, an analyst at Eurasia Group. “We are a long way off saying this is a 1990s redux.” What is clear is that Abiy’s campaign to centralize power in the capital is in tatters. With many regions seeking more devolution, the conflict threatens the integrity of the state, according to a key Western diplomat, who asked not to be identified citing the sensitivity of the matter. Abiy’s authority is at serious risk unless he can find a way to force the Tigrayans back. The Nobel peace prize winner has awakened more enemies than just the TPLF. “We have one thing in common and that is we are fighting the same enemy,” said Kumsa Diriba, the commander-in-chief of the Oromo Liberation Army.47

The belligerence on both sides is unmistakable. And it is often the belligerence of this typology that often leads to breakdown of possibility of peaceful settlement through political dialogue. It is when either sides or at least one side profess messianic zeal (such as has been demonstrated beyond all reasonable doubt by the Ethiopian Prime Minister, Mr. Abiy Ahmed) that this tipping point is reached. And AU and the regional body have demonstrated their incompetence and ineffectiveness in this regard. There is no denial of the risks faced by both sides of the conflict, apart from the feared humanitarian crisis getting out of control – akin to what happened in Darfur. The type of optimism about the survival and sustainability of the Ethiopian State, probably well-placed, is however mediated by the circumstances of the present situation. Such optimism was witnessed prior to the final breaking away of Eritrea in 1991 which unfortunately crashed when reality dawned on Ethiopia that the break-up has become a fait accompli. Pretending that things are alright with Ethiopia because it still has command over the state structures particularly the instrument of inflicting violence and punishment, the military and other security forces, is like the foolish ostrich burying its head deep in the sand amidst all extant environmental dangers.

Matt Bryden, from the think tank Sahan Research, doubts that a political solution can be found at this stage, especially between two main antagonists. “The Tigray Defense Forces has to weigh up the prospect of political dialogue with the risk of losing the [military] initiative. On the other side, Mr. Abiy shows no interest or understanding that he might need to engage in political dialogue. He has… an unshakeable belief in himself and his mission. “I’m afraid we’re likely to see conflict continue until either Tigray is essentially liberated or – less likely – until both sides find themselves in a hurting stalemate,” Mr. Bryden says.48

The window of opportunity for political dialogue or alternative dispute resolutions has unfortunately closed – though it can still be re-opened. What has become clear, however, is that Abiy Ahmed-led so-called “political reforms” have turned sour, leading to conflict between the central government in Addis Ababa and the regional capital of Mekelle in Tigray. But what type of political reforms? Populist oriented, in short, and rightwing in character to shortchange Tigray for what it was perceived to be its long hold on power in Addis Ababa after the overthrow of the Marxist military rulers in 1991. Abiy Ahmed’s brinksmanship and/or pugilist statecraft has almost pushed Ethiopia over the tipping point. Of course, there are new dynamics, indeed strange paradoxes thrown into the mix. For instance, having Eritrea fighting on the side of Ethiopia, despite what both sides have earlier inflicted on themselves few years back, is largely literally inexplicable. But that is the phenomenal reality that makes the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict a complex entity.

Caught in the Horn of a Dilemma

The Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict has brought the Horn of Africa the risk of further destabilization. This is because all the countries in the region has a stake or the other, and from one degree to another, in the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict. Nearly all the countries in the region have one axe or the other to grind with Ethiopia for one reason or the other. It seems to be Eritrea that is the only country that has axe to grind with Tigray for historical reasons that are rooted in the Ethiopian-Eritrean civil war that led to the breakaway of Eritrea in 2011, precisely a decade ago.

The conflict has also brought the region and the Gulf of Aden into a kind of head-on collision but in which one can see the ebb and flow of power between the two regions. Discernible in this regional struggle for dominance are diplomatic, strategic and commercial interests that converge at one of the world’s most important chokepoints: the Red Sea. However, the convergence of these interests at the Red Sea also diverges and disperses along the individual countries’ foreign policy or hegemonic thrusts – thus making it impossible to reconcile these interests to the mutual benefits of the countries concerned.

Who gains the upper hand in this power struggle between the two regional power blocs? In early 2020, the Horn and Gulf countries trooped like gazelles to the Saudi capital, Riyadh, to launch the new Council of Arab and African Littoral States of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. There were representatives from Somalia, Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Jordan and Yemen.

But conspicuously missing in action or the camaraderie was Ethiopia. Ethiopia was missing in the theatre because it already has its cup storming with crisis it instigated by itself through its prebendalist outlook in the Horn of Africa region. It is precisely this prebendalism that has constrained it from successfully projecting its power beyond the Horn of Africa to the Gulf Aden in this case in a reverse manner. Its foreign policy has been stymied by lack of clarity of what it precisely wants (except perhaps its narrowed interpretation of selfish Oromo ethnic-dominated government in Addis Ababa). Its sixty-year effort at containing Egypt has come to naught.

From the Gulf is Saudi Arabia on the one hand trying to attempt to assert its power and project same to the Horn to checkmate the rising profiles of Turkey and Iran that have their specific ambitions being projected to the Horn. Indeed it is the manifest quest of both Turkey and Iran individually to contain Saudi Arabia. However, in the mix are thrown the heavyweights of the United States (who is the godfather of Saudi Arabia) and China (neither directly supporting Iran nor Turkey) also vying for dominance through their privies or proxies.

The regional dimension to the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict is analogous to the complex web of the Nile tributaries with their origins in Ethiopian highlands. The entire Horn of Africa is enmeshed in the geopolitical crisis between Ethiopia and Tigray leaving no stone unturned in the political upheavals of the affected individual countries. Even though each country seem to be treading carefully in this new minefield of the Horn of Africa, their involvement in the Ethiopian-Tigrayan ongoing conflict can be traced directly to their antagonism with Ethiopia for one reason or the other and from one degree to another.

For instance, largely muted in the media are the simmering disputes between Ethiopia and Sudan which has, however, cast its dark pall on the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict. Sudan has been unwittingly drawn into the vortex of the conflict because of the tragic humanitarian fallouts of the conflict.

According to Amelia Twitchen “particular focus has fallen to Sudan, as many of those fleeing the violence in Tigray have headed west to the Sudan border. This influx has been greater than expected and the UN is planning for the arrival of around 200,000 more refugees over the next six months.49

Even before violence began in Ethiopia, Sudan was already home to over one million refugees, mainly from South Sudan. The influx of refugees from Ethiopia will inevitability put further pressure on the existing humanitarian relief efforts in Sudan, where camps are overcrowded and food, medicine and shelter are urgently needed.50

According to Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, United States, “[t]he armed clashes along the border between Sudan and Ethiopia are the latest twist in a decades-old history of rivalry between the two countries, though it is rare for the two armies to fight one another directly over territory. The immediate issue is a disputed area known as al-Fashaga, where the north-west of Ethiopia’s Amhara region meets Sudan’s breadbasket Gedaref state. Although the approximate border between the two countries is well-known – travellers like to say that Ethiopia starts when the Sudanese plains give way to the first mountains – the exact boundary is rarely demarcated on the ground.51

Borders in the Horn of Africa are fiercely disputed. Ethiopia fought a war with Somalia in 1977 over the disputed region of the Ogaden. In 1998 it fought Eritrea over a small piece of contested land called Badme. About 80,000 soldiers died in that war which led to deep bitterness between the countries, especially as Ethiopia refused to withdraw from Badme town even though the International Court of Justice awarded most of the territory to Eritrea. It was re-occupied by Eritrean troops during the fighting in Tigray in November 2020.52

After the 1998 war, Ethiopia and Sudan revived long-dormant talks to settle the exact location of their 744km-long (462 miles) boundary. The most difficult area to resolve was Fashaga. According to the colonial-era treaties of 1902 and 1907, the international boundary runs to the east.53

This means that the land belongs to Sudan – but Ethiopians had settled in the area and were cultivating there and paying their taxes to Ethiopian authorities. Negotiations between the two governments reached a compromise in 2008. Ethiopia acknowledged the legal boundary but Sudan permitted the Ethiopians to continue living there undisturbed. It was a classic case of a ‘soft border’ managed in a way that did not let the location of a ‘hard border’ disrupt the livelihoods of people in the border zone; there was coexistence for decades until just now, when a definitive sovereign line was demanded by Ethiopia.54

The Ethiopian delegation to the talks that led to the 2008 compromise was headed by a senior official of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), Abay Tsehaye. After the TPLF was removed from power in Ethiopia in 2018, ethnic Amhara leaders condemned the deal as a secret bargain and said they had not been properly consulted. Each side has its own story of what sparked the clash in Fashaga. What happened next is not in dispute: the Sudanese army drove back the Ethiopians and forced the villagers to evacuate.55

At a regional summit in Djibouti on 20 December [2020], Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok raised the matter with his Ethiopian counterpart Abiy Ahmed. They agreed to negotiate, but each has different preconditions. Ethiopia wants the Sudanese to compensate the burned-out communities; Sudan wants a return to the status quo ante. While the delegates were talking, there was a second clash, which the Sudanese have blamed on Ethiopian troops. As with most border disputes, each side has a different analysis of history, law, and how to interpret century-old treaties. But it is also a symptom of two bigger issues – each of them unlocked by Mr. Abiy’s policy changes.56

The Ethiopians who inhabit Fashaga are ethnic Amhara – a constituency that Mr. Abiy increasingly hitched his political wagon to after losing significant support in his Oromo ethnic group, the largest in Ethiopia. Amharas are the second largest group in Ethiopia and its historic rulers.57

Emboldened by the federal army’s victories in the conflict against the TPLF over the last two months, the Amhara are making territorial claims in Tigray. After the TPLF retreated, pursued by Amhara regional militia, they hoisted their flags and put up road signs that said “welcome to Amhara”. This was in lands claimed by Amhara state but allocated to Tigray in the 1990s when the TPLF was in power in Ethiopia.58

The Fashaga conflict follows the same pattern of claiming sovereignty – except that it is not about Ethiopia’s internal boundaries, but the border with a neighbouring state. The failure to resolve it peacefully is the indirect result of another of Mr. Abiy’s policy reversals: Ethiopia’s foreign relations. For 60 years, Ethiopia’s strategic aim was to contain Egypt, but a year ago Mr. Abiy reached out a hand of friendship. The two countries each regard the River Nile as an existential question. Egypt sees upstream dams as a threat to its share of the Nile waters, established in colonial era treaties. Ethiopia sees the river as an essential source of hydroelectric power, needed for its economic development. The dispute came to a head over the construction of the huge Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (Gerd).59

The bedrock of the Ethiopian foreign ministry’s hydro-diplomacy used to be a web of alliances among the other upstream African countries. The aim was to achieve a multi-country comprehensive agreement on sharing the Nile waters. In this forum, Egypt was outnumbered. Sudan was in the African camp. It was set to gain from the Gerd, which would control flooding, increase irrigation, and provide cheaper electricity. Egypt wanted straightforward bilateral talks with the aim of preserving its colonial-era entitlement to the majority of the Nile waters.60

In October 2019, Mr. Abiy flew to the Russia-Africa summit at Sochi. On the side-lines he met Egyptian President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi. In a single meeting, with no foreign ministry officials present, Mr. Abiy upended Ethiopia’s Nile waters strategy. He agreed to Mr. Sisi’s proposal that the US treasury should mediate the dispute on the Gerd. The US leaned towards Egypt. If the young Ethiopian leader, who had just won the Nobel Peace Prize for ending tensions with Eritrea, thought he could also secure a deal with Egypt, he was wrong. The opposite happened: the 44-year-old cornered himself. Sudan was the third country invited to negotiate in Washington DC. Vulnerable to US pressure because it desperately needed America to lift financial sanctions imposed when it was designated a “state sponsor of terrorism” in 1993, Sudan fell in with the Egyptian position. Ethiopian public opinion turned against the American proposals and Mr. Abiy was forced to reject them, after which the US suspended some aid to Ethiopia. US President Donald Trump warned that Egypt might “blow up” the dam, and Ethiopia declared a no-fly zone over the region where the dam is located.61

The TPLF has allies in Kassala in Eastern Sudan, as well as old friends in Khartoum, who may find it opportune to help them with supply routes in order to hit back on Addis Ababa’s stand on al-Fashaga. (It would also be a throwback to Sudan’s TPLF-friendly policies in the 80s and 90s when the Derg controlled Ethiopia.)62

The chilly reception given to Sudanese Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok during a recent visit to Addis Ababa, as well as a statement by al-Burhan, indicate that any goodwill gathered by Abiy in the early phase of his tenure is now spent political capital. The other major regional player is Egypt, which has long sought to pressure Addis Ababa over the use of Nile waters.63 The Arab nation already backs Sudan against Ethiopia on the Nile issue. While Cairo had long used Asmara as a proxy to pressure Addis, now that Isaias and Abiy are in cahoots, Egypt may shift its support to the TPLF to divert Ethiopia’s attention from finishing the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. The TPLF leadership may look differently at the GERD as a consequence of the war, and the prospects of Tigray possibly seeking secession from Ethiopia.64

History aside, Sudanese and Egyptian support for the TPLF would be a game-changer. Such foreign backing could secure the Tigrayan forces with a steady source of supplies, safe havens for exiled leaders, and transit points for travel in and out of TDF-controlled areas. This explains the current TDF offensive on the western fronts in Tigray, as informed by interlocutors close to TDF, in order for the Tigrayan forces to create a corridor to the Sudanese border.65

It is obvious that Abiy Ahmed’s often ill-thought unilateral decisions – in line with his incipient authoritarian tendencies – have rail-road him into a quandary from which he now finds it difficult to extricate himself. This is a reflection of his political immaturity despite what can be seen as his intellectual sophistries. His intellectual sophistries-cum-political immaturity has only earned him more troubles than he can reasonably handle through the framework of modern statecraft.

Somalia is also in the larger regional picture which further compounds the escalating strategic scenario in the region.

Historically, Somalia has viewed Ethiopia with suspicion, but Abiy’s diplomatic charm won over President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed ‘Farmaajo’, who at the time was only one year into his presidency. When the tripartite alliance was created between Abiy, Farmaajo, and Afwerki, analysts believe one of its main, albeit indirect, goals was to oppose federalism. Without that base, Eritrea’s strongman Isaias Afwerki is unlikely to have participated. For Farmaajo, Ethiopia’s reconciliatory diplomacy provided him with the opportunity to consolidate power in Mogadishu. After its inception, he exploited the alliance to undermine federalism in Somalia and suppress opposition, mainly from the country’s elite.66

But looming larger in the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict is the role of Eritrea, a highly militarized and fortified one-party state held by the jugular by Isaias Afwerki as the President. This role is, however, rooted in the complex web of internal politics of Eritrea where President Isaias Afwerki has successfully instituted authoritarian rule over the last one decade with the corollary militarization of the Eritrean society, destruction of the realm of civil society organizations, caging the media including egregious violations of human rights.

Eritrea had initially denied any involvement in the Ethiopian-Tigrayan conflict. But this plausible deniability (which may appear so to the gullible) was soon blown away by the preponderance of evidences clearly showing its military and involvement in the ongoing war between the two gladiators. It was forced to admit its involvement shame-facedly when it can no longer hide under any pretext.

Eritrea has [therefore] acknowledged for the first time its forces are taking part in the months-long war in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region and promised to pull them out in the face of mounting international pressure.67

The explicit admission of Eritrea’s role in the fighting came in a letter posted online […] by the country’s information minister, written by its ambassador to the United Nations and addressed to the Security Council. For months, the Ethiopian and Eritrean governments denied Eritreans were involved, contradicting testimony from residents, rights groups, aid workers, diplomats and even some Ethiopian civilian and military officials. Tigray residents have repeatedly accused Eritrean forces of mass rape and massacres, including in the towns of Axum and Dengolat. Abiy finally acknowledged the Eritreans’ presence in March while speaking to MPs, and promised soon after that they would leave.68

[The] letter from Eritrea said, with the TPLF “largely thwarted”, Asmara and Addis Ababa “have agreed – at the highest levels – to embark on the withdrawal of the Eritrean forces and the simultaneous redeployment of Ethiopian contingents along the international boundary”. It came a day after UN aid chief Mark Lowcock told the Security Council that despite Abiy’s earlier promise, there had been no evidence of a withdrawal of Eritrean troops from the region. He also said aid workers “continue to report new atrocities which they say are being committed by Eritrean Defence Forces”.69

William Davison, the International Crisis Group’s (ICG) senior analyst for Ethiopia, told Al Jazeera that Eritrea’s admission came as […] increasing proof made it harder to continue denying the presence of its forces in Tigray. “Obviously, with that mounting evidence [came] increasing international pressure,” he said. “Ethiopia’s government admitted the Eritrean presence and said they would withdraw and Eritrea said nothing; that did lead to suspicions that there was a difference between the two governments who are allies in this conflict in Tigray, so perhaps Eritrea’s government also wanted to dispel the idea that there was any major split between Addis Ababa and Asmara.”70

Looking ahead, Davison said it was a matter of the international community to monitor “very carefully” whether the Eritrean troops will indeed leave Tigray. “[That is] because, of course, up until now, the two governments have completely denied Eritrea’s presence. So therefore, there’s no particular reason to take them at their word that this withdrawal commitment will be implemented.”71

The idea of Eritrean troops waging war in Tigray is condemned as reckless endangerment of civilian lives by Western diplomats and as a travesty of Ethiopian sovereignty by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s domestic detractors. But from the point of view of Ethiopia, Eritrea’s involvement could be best understood as a tragic but explainable option given the grave alternatives.72

Appreciating the stakes at the start of the conflict in early November [2020] is crucial. Following a swift and coordinated attack against federal army positions in Tigray region on November 3, the TPLF instantly became a formidable military force taking possession of more than half of the country’s military equipment. Additionally, the attack effectively incapacitated the northern command of the national army based in Tigray. With most of the national arsenal out of the federal government’s hands, and the national army’s best force incapacitated, TPLF’s forces next step seemed to be a match south on Addis Ababa.73

The scenario of a heavily-armed 250,000-strong regional rebel army marching towards the capital presented the Federal government a stark choice between capitulating, launching a prolonged pushback, or, in the best case, negotiating a settlement in which the TPLF would have a position of military and territorial advantage. All three scenarios would lead to nationwide security and political crisis, with potential for collapse of the central government.74

In the first case, the return of the TPLF to national power, whether by fait accompli as the federal forces capitulate or by agreed compromise, would not be accepted by other regional states, most notably the Amhara, Oromia, and Somali regions. Leaderships there have been outspoken in their opposition to the TPLF.75 In the second scenario, prolonged fighting carried on between the central government and Tigray forces, likely expanding into the centre of the country and involving several regional and paramilitary forces. This was the most catastrophic scenario, particularly because most regions have built up massive special armed forces.76

The more likely scenario seemed a protracted and all-encompassing civil war, creating, at best, a stalemate paralyzing the Ethiopian government. At worst, this created the danger of a full state collapse destabilizing the Horn of Africa.77

External Eritrean support might have averted this by tipping the scales in favour of the Federal Government of Ethiopia. The TPLF’s leadership seems to have feared precisely this likelihood. The group’s leadership has sought to alert the world about, and politically pre-empt, the potential involvement of Eritrea in a war they said was imminent.78

The Tigray war is about the survival of the central government of Ethiopia, hence the maintenance of basic political order. This does not guarantee the justice or liberty which the populations on either side of the warring parties want, but it is a basic prerequisite for those aims. The preservation of political order is not a democratic endeavour, but one of statehood – and, as such, it is not the exclusive turf of democratic states.79 In that sense, if indeed Eritrean support had shifted the outcome of the conflict, that is a gain in terms of political order, not only in Ethiopia but the entire Horn of Africa.80

Eritrea’s involvement in the war, on the other hand, would certainly be followed by darker legacies. The possibility of atrocities being committed against the Tigrayan population, and the vulnerability of Eritrean refugees in Tigray are grave consequences that could overshadow the gains of restoring political order, or even sow the seeds of threat to political order itself.81

The stark choice that presented itself, it seems, was one between averting the collapse of the central government of Ethiopia and ensuring that only clean hands would do the job. This is a dilemma which no national leader would want to confront. It is an eventuality that the TPLF leadership could have easily foreseen when kick-starting the conflict. They likely dismissed it as less probable, or accepted it as a cost of maintaining their power.82

To understand current Eritrean policies, one needs to discern the mindset of its autocratic president, the former guerrilla leader of Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), who has ruled the totalitarian one-party state with an iron fist since independence.83 The Eritrean state was born out of a 30-year liberation war. Its current military adventure in Tigray may lead to its collapse. What is Eritrea’s objective in the war? And, how will it impact the one-man rule of President Isaias Afwerki?84

Isaias has incessantly demarcated the borders of Africa’s second newest country through bloodshed and sacrifices—as Eritrea has been at war with all its neighbours since its independence in 1993. In 1995, it clashed with Yemen over the Hanish Islands in the Red Sea and in 1996 with Sudan, before the devastating border war with Ethiopia from 1998-2000. In 2008, Eritrea picked a fight with its tiny southern neighbour Djibouti, also over a strip of contested territory. In all these conflicts, Eritrea was the first to launch military engagement—and tens of thousands of youths have perished on the battlefields to sustain the image of the country as an invincible warrior nation.85

Isaias, meanwhile, attributes blame for the endless conflicts brought upon Eritrea to external forces, usually the USA, which he claims harbours an interest to “keep Eritrea hostage through the continuous fomenting and ‘managing’ of crises.”86

Eritrea has been called the modern Sparta State, as its martial traditions with never-ending military service and constant war campaigns resemble that of the ancient Greek city-state. Isaias asserts that the Eritrean nation was born through sacrifice and blood, and the new post-independence generations need to suffer and experience shared hardships as endured by their parents, to constantly recreate and manifest an Eritrean nationalist military ethos. Compulsory military national service for all women and men between the ages of 18 and 55 was imposed soon after independence. It was supposed to be limited to an 18-month period of service, but since the outbreak of the Ethiopian war in 1998, many have been forced to remain on duty. Youth recruited to fight Ethiopia in the late 1990s are now middle-aged. Today, once again, they are engaged in the war in Tigray.87

In 1998 Eritrea launched an offensive against Ethiopia, ostensibly over a sliver of territory along the border to Tigray. The war’s root causes, however, were found in differences of ideology, economic policy, and development visions between the two new governments in Asmara and Addis Ababa.88

The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) constituted the senior Ethiopian political and military leadership at that time, as they were the dominant party within the EPRDF government coalition. When attacked, the late Ethiopian Prime Minister and former TPLF guerrilla leader Meles Zenawi ordered full war mobilization in Ethiopia, and the regional leadership in Tigray called back the old guerrilla army to service.89

During a two-year period of fighting, over 100,000 combatants were killed, before the Ethiopian army finally managed to crush the Eritrean forces and push them out of Tigray.90

The humiliating military defeat of his ‘invincible’ army has been a heavy burden for Isaias to carry ever since. The current full-scale military invasion of Tigray is thus likely driven by the desire for vengeance and to settle old scores, as Isaias apparently has ordered his forces to undertake what may appear to be a genocidal campaign against Tigrayans.91

Beyond vengeance against the TPLF, some argue that Isaias also harbours an interest in unmaking the ethnic configuration of the Ethiopian federation, with the aim of realigning Eritrea with Ethiopia—a vision staunchly opposed by TPLF but seems to be backed by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. Issues on the table include a federal/ confederal arrangement, the merger of the two national armies, an Ethiopian navy base in the Eritrean Red Sea ports, and joint mineral exploration in border areas.92

In spite of possible benefits, Eritrean nationalists in exile are afraid Isaias will squander the hard-won independence, for the sake of his own personal ambitions to become the ‘big man’ of the Horn of Africa in an Eritrean-Ethiopian federation.93

The authoritarianism of Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea is unmistakable. There is no more doubt that he is a wily gladiator. So also his predilections for gunboat diplomacy in the Horn of Africa! Even though Eritrea has been independent for the past decade after a gruesome national liberation war of over three decades, Eritrea has not benefitted much from this independence. It has not reaped the expected economic or political dividends because of the iron-fisted rule of Afwerki accompanied by his gross incompetence in managing a newly independent country. He substituted his personal ambitions to rule as long as possible for the development of Eritrea along the lines of economic progress and political liberalism. Afwerki wants to be the grandmaster of the Horn of Africa/Gulf of Eden without the necessary economic development. He is basing his calculation on the illusory might of the Eritrean Military which defeated Ethiopia in the long-drawn national liberation war that culminated in the sovereign independence of Eritrea in May 2011.

Eritrean foreign policy can, therefore, be seen to be based on what can be called Afwerki Doctrine in which Isaias Afwerki wants Eritrea to be the grandmaster of the Horn of Africa and Gulf of Aden. The Afwerki Doctrine is based on the Machiavellian principles of playing one country against the other or exploiting every available weakness and opportunity that present themselves in any country that falls into internal crisis. This Doctrine cannot be said to be based on any known moral imperative but on Darwinian instinct of self-preservation in power by Afwerki. But the Doctrine has its Achilles Heel which lies in the collapsible Eritrean State superstructure not supported by any visible powerful economic development. It may last for some time but either a slight or seismic push will tip it over into final collapse and destruction inevitably with the overthrow of Isaias Afwerki himself as many examples in history of other countries have shown in the last few years in Africa.

Some observers fear that the Tigray conflict could turn Ethiopia into the ‘Libya of East Africa’, an unfortunate nod towards the true scale this conflict could take on. Hundreds have already been killed and thousands displaced, but regardless of how much longer the violence lasts for, what is certain is that the impacts on the wider region will continue long after the cessation of hostilities, whenever that may occur. It remains to be seen how this will affect Sudan in particular, though one unavoidable fact is that increased flow of refugees will put further pressure on the country’s already-fragile situation, particularly in terms of food insecurity.94

As the conflict between the Ethiopian federal government and the Tigray regional government continues, serious concerns are arising about how it will impact East Africa’s peace and security in both long and short terms. The combination of civil conflict, increased flows of refugees and environmental challenges, all being faced whilst in the midst of a global pandemic, present serious challenges for the region’s security, as well as for the human rights of those caught up in the violence.95

The Tigray war will therefore impact politics, social cohesion, and development all over the country, just like the 1974-1991 Tigrayan struggle.96

The military campaign on Tigray will be remembered as Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s “crossing the Rubicon” moment. No matter the outcome, or how long it will take to reach a victory or settlement, Ethiopia will likely never return to the status quo ante.97

Ethiopia, Tigray and Eritrea have boxed themselves into serious problematique that are clearly capable of unravelling them as States and region. Of course, this will not happen overnight. It will most probably be a long-drawn process that may even take many years, except they quickly retreat from their political and military grandstanding belligerency including moral righteousness.

AU Caught Napping Again

Many factors and forces have been critically interrogated by scholars and analysts as being responsible for the lack of effectiveness and efficacy of the African Union (AU) in solving African conflicts especially. However, there is one powerful factor that looms writ large either in the background or foreground (depending on the view of the scholar). It is the leitmotif of “African solutions to African problems” which is predicated as it is on the alleged capacity of the AU to embark on appropriate interventions to ensure that such conflicts, crises and disputes are resolved within a reasonable time frame. However, the reality has been the exact opposite of this wish or wisdom.

Around this dominant factor revolves round other subset of factors. The first is the relative resilience of the forces at play in the emergent conflict, their aims and the ability or inability to manage a consensus situation with the opposing forces. The second is the elasticity of the strength of the residual power of the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of the sovereign state involved in conflict. At what point would African Union be willing to intervene “forcefully” in the internal affairs of a sovereign state?

The third factor has been argued to be lack of AU’s practical military capacity for intervention in conflict situation. But this is largely begging the issue. Africa has provided military personnel as peace-keeping force in many countries in the past and present. The real issue is the complex situation that African peace-keeping forces find themselves in more often than one case. The complexity often overwhelms the capacity of the African peace-keeping force from keeping the peace.

According to Chris Changwe Nshimbi of University of Pretoria, “Seven years ago African leaders committed themselves to working towards an end to armed conflict. As they marked the 50th anniversary of the founding of the African Union they swore to ensure lasting peace on the continent. They pledged not to bequeath the burden of conflicts to the next generation of Africans.”98

The pledge was followed by the adoption in 2016 of the Lusaka Road Map to end conflict by 2020. The document outlined 54 practical steps that needed to be taken. They focused on political, economic, social, environmental and legal issues. They ranged from adequately funding the African Standby Force for deployment, to stopping rebels or insurgents and their backers from accessing weapons. Other steps included fighting human trafficking, corruption and illicit financial flows.99

At the time of the declaration, Africa had disproportionately high levels of conflict. State and non-state actors in Africa waged about 630 armed conflicts between 1990 and 2015. Conflicts orchestrated by non-state actors accounted for over 75% of conflicts globally.100

The efforts to ‘silence the guns’ has been singularly ineffective. Since the pledge was signed conflict in Africa has increased.101

One reason for the failure is that the 2020 goal was too ambitious given the number of conflicts on the continent. The second reason is that many are internal, arising from the grievances citizens have with their governments. This internal dynamic appears to have been ignored from the outset.102

Prominent conflicts by non-state actors include the Tuareg separatist and jihadist insurgencies in Mali, Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria, jihadist and militia insurgencies in Burkina Faso, al-Shabaab in Somalia, and the ethnic war in the Central African Republic. The most notable civil wars are those in Libya, South Sudan and the one waged by Anglophone Ambazonia separatists in Cameroon.103

Most conflicts are generally centred on these areas:

- Sahel region, including Mali, Burkina Faso, Northern Nigeria, Chad, Sudan and Eritrea

- Lake Chad area, including Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria

- Horn of Africa, including Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan and Kenya, and

- Great Lakes region, notably Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda and Uganda.

Though domestic, most of these conflicts tend to be cross-border in form. They threaten interstate and regional stability. For example, al-Shabaab in Somalia exploits porous borders to carry out deadly attacks in Kenya.104