By Alexander Ekemenah, Chief Analyst, NEXTMONEY

Introduction

The ink being spilled on commenting on the Guinean coup of September 5, 2021 has hardly dried up when another coup took place at the other end of Africa but this time unsuccessful. This time around it was in Sudan where elements allegedly loyal to the dethroned Omar Hassan al-Bashir staged a coup to overthrow the Sovereign Council of Sudan headed by Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok on September 21, 2021.

According to media reports, at least 40 officers were arrested at dawn on Tuesday 21 September 2021. A government spokesman said they included ‘remnants of the defunct regime’, referring to former officials of President Omar al-Bashir’s government and members of the country’s armoured corps.1

The Sudanese PM Abdallah Hamdok during a speech revealed that the coup attempt was largely organized by loyalists of the ousted leader Omar al-Bashir. He added that the perpetrators involved in the failed coup were not only from the military but also outside the military as well. According to some Sudanese officials, soldiers attempted to take over a state media building in Omdurman, but they were subsequently prevented and apprehended. Security forces reportedly shut down the main bridge connecting the capital Khartoum to Omdurman.2

Dozens of troops who participated in the attempted coup d’état were apprehended. They were all believed to be loyalists of al-Bashir, according to Sudan’s information minister Hamza Balul.3 A witness said that military units loyal to the council had used tanks to close a bridge connecting Khartoum with Omdurman early on Tuesday morning.4 [The coup] was not the first challenge to the transitional authorities, who say they have foiled or detected previous coup attempts linked to factions loyal to Bashir, who was deposed by the army after months of protests against his rule [on April 11, 2019].5 In 2020, Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok survived an assassination attempt targeting his convoy as he headed to work in Khartoum.6

Sudan has gradually been welcomed into the international fold since the overthrow of Bashir, who ruled Sudan for almost 30 years and is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) over alleged atrocities committed in Darfur in the early 2000s.7 Bashir is presently in prison in Khartoum, where he faces several trials.8 The ICC’s chief prosecutor held talks with Sudanese officials last month [August 2021] on accelerating steps to hand over those wanted over Darfur.9

Sudan’s economy has been in deep crisis since before Bashir’s removal and the transitional government has undergone a reform program monitored by the International Monetary Fund.10 Underlining Western support for the transitional authorities, the Paris Club of official creditors agreed in July to cancel $14 billion of Sudan’s debt and to restructure the rest of the more than $23 billion it owed to the club’s members.11 But the economy is still struggling with rapid inflation and shortages of goods and services.12

The coup attempt is not the first to target the transitional government formed after the April 2019 ouster of Omar al-Bashir, who was overthrown after 30 years of undivided rule.13

Sudan has seen several coups in the 20th century, the most recent of which — a military coup with Islamist support — brought Bashir to power in [June] 1989. Bashir has been imprisoned in Khartoum since his removal from office and is currently on trial for his participation in the coup. He is also being tried by the International Criminal Court for “genocide” and crimes against humanity during the conflict in Darfur (west).14 The Troika (United States, Great Britain and Norway), which is in charge of the Sudanese file, condemned the coup attempt, while the UN mission in Sudan said it refused “any call to replace the transitional power with a military power”.15

On Tuesday, the powerful paramilitary leader and member of the Sovereignty Council, Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, a former member of the Bashir regime nicknamed “Hemedti”, declared in a speech to his fighters: “We will not allow a coup”. “We want a real democratic transition with free and fair elections,” he added, according to the official Suna agency.16

In place for more than two years, the civilian-military cabinet, born of an agreement with the movements that led the popular mobilization against Mr. Bashir, was supposed to take Sudan to a fully civilian power in three years. But his mandate was extended when a historic peace agreement was signed in October 2020 with a coalition of rebel groups, giving him until 2023 to complete his mission.17

The coup attempt (…) clearly underlines the importance of introducing reforms in the army and the security apparatus,” the Prime Minister said on Tuesday. The Hamdok government also wants to put an end to the economic crisis, undertaking a series of difficult reforms in order to benefit from a debt relief program of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These measures, which include cutting subsidies and introducing a controlled floating of the local currency, have been seen as too harsh by many Sudanese. Sporadic demonstrations have recently taken place against these reforms and the rising cost of living.18

According to a report by Mohammed Amin in late July 2019 in reference to the coup that took place just about three months after Omar al-Bashir was overthrown on April 11, 2019: Sudanese Islamists are under intense pressure, as the ruling Transitional Military Council (TMC) wages an ongoing arrest campaign against them following the Wednesday announcement an alleged coup was foiled.19

Sources have told Middle East Eye that, under instructions from the TMC, forces have been hunting down Islamists under the accusation that they have been destabilising the country and attempting to topple the military leaders that took power following the removal of President Omar al-Bashir.20

Sources within the army and analysts believe that the confrontation between the Islamists and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia, headed by TMC deputy head Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemeti, is expected to escalate in the coming period. The TMC is currently working on an agreement with Sudanese protest and opposition groups that would see its influence entrenched as the country moves out of the Bashir era.21

A senior officer in the Sudanese army told MEE that at least 140 senior and junior officers have been arrested in the campaign so far. Those seized come from various units, in and outside the capital Khartoum. The source, who spoke on condition of anonymity over security concerns, said the arrest campaign is the largest ever within the national army. “I expect more will be arrested,” the source said.22

Bashir’s ruling National Congress Party (NCP) was dominated by Islamists, and on Wednesday the Sudanese military said members of the NCP and Islamic Movement were involved in the alleged coup plot. The plot aimed “to return the former National Congress regime to power” and scupper the ongoing negotiations the TMC is holding with the opposition, the military said in a statement. “At the top of the participants is General Hashim Abdel Mottalib, the head of joint chiefs of staff, and a number of officers from the National Intelligence and Security Service [NISS],” it said.23

According to the army officer, Hemeti has ordered Sudan’s security organs to be restructured – particularly the operations unit of the NISS. “The entire operations unit, which contains more than 10,000 soldiers working under the command of NISS, has been given only two options: whether to restructure and join the RSF, or be demobilized and disarmed,” the source said. The source added that the army, backed by the RSF, has arrested dozens of Islamists and leaders of the old regime, including former Vice President Bakri Hassan Salih and Secretary-General of the Sudanese Islamic Movement al-Zubair Mohamed al-Hassan, among others. “So far at least 40 Islamist figures have been arrested, in addition to the 23 people already in detention, including President Omar al-Bashir,” he said.24

MEE has not been able to independently verify whether a coup attempt was indeed thwarted, or when it was supposed to have taken place. Last month the military made a similar claim it had averted a putsch. Security sources told MEE at the time that the army exaggerated its claim to strengthen its position in power-sharing talks with the civilian opposition.25

For its part, the Sudanese Islamic Movement has dismissed the allegation, stressing that its members and supporters aren’t involved in any such activities. “The Sudanese Islamic Movement is very keen on the stability and prosperity of Sudan, so it has kept monitoring the situation and the current developments in Sudan closely. This is why it has left everything to the TMC to manage. But it has noticed that it has been blamed for anything wrong that has happened in the country over the last period,” it said in a statement. “Our leaders weren’t involved in any coup attempt and have nothing to do with military coups, so we call on the TMC to bring forward proof and evidence of these accusations.”26

However, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) opposition alliance said it welcomed the TMC’s efforts in controlling and saving the country in the face of an attempted counter-revolution. Satia al-Haj, a leading FFC member, told MEE that the counter-revolution, represented by the Islamic Movement and NCP, continuously attempts to derail the revolution and obstruct the establishment of civilian rule and democracy. “We can’t confirm if they really committed this coup attempt or not. But we can definitely say that they are attempting by all means to sabotage the revolution, and the national army is now responsible for stopping that and protecting the country from the destabilisation,” he said.27

However, the leader of Bashir’s defence team, Mohamed al-Hassan al-Amin, noted that anyone who has been arrested is supposed to be presented in court or released. Amin, who was a prominent NCP leader, said the TMC should follow the proper legal procedures with all citizens. “As long as we are talking about democratic transformation and reformation in the coming period, we are supposed to follow the right legal steps when we accuse anyone of committing anything. So we urge the TMC to bring anyone that is suspected of any crime to court, not put him in jail,” he argued.28

Sudanese military expert Abdul Aziz Khalid believes that allegations of military coups will continue as competition over influence in the army grows. He said the arrests were “preventative measures” by the TMC in an attempt to stop any potential moves to remove the council from power. “The two powers of the TMC and the pro-Islamists are apparently working against each other within the regular forces, including the army, security and even the police, so it’s very probable that they may go for further confrontation,” he said.29

Political analyst Salah al-Doma said that Hemeti’s wide restructuring and the arrests showed the factions of the old regime in and out of the TMC had failed to coexist following Bashir’s removal. He said that despite them once belonging to the same regime, previous regional armed conflicts in the country’s west and south and a conflict of interests had put them on a collision course. “The regional effect as well as the political and economic interests, in addition to the pressure of escalation in the streets, all accelerated the potential of clashes between the old guard Islamists and the commanders of the TMC backed by the RSF,” the professor at Omdurman Islamic University told MEE.30

The latest coup in Sudan, just barely two weeks after that of Guinea, has once again raised the spectre of military rule gradually stealing its way back into the governance space in Africa. The coup in Sudan is the second unsuccessful one this year alone. The first was that of Niger which took place on March 31, 2021. The coup underscored the political fragility or instability that has become the lot of Sudan over the decades within the context of transitional arrangements and regimes that are simply “transitional”.

The coup also took place amidst crisis generated by an unsettled past. Sudan, even after South Sudan split away in May 2011, is still facing many unanswerable questions about its past particularly the atrocities it willfully inflicted upon itself by an authoritarian regime which earned Sudan a pariah status from the international community for more than two decades. It is precisely when Sudan is seen to be struggling with its past and trying to chart a new path forward that this coup attempt came like a thunderbolt from the deep and black cloud overhead or spanner thrown into a revved-up engine to stop the machine from working or slow it down.

Sudanese society is still badly fractured. And it was Omar al-Bashirian regime that deepened the fractures. Even when the country is seen to be predominantly Muslim, there are still many tribal and social divisions. The new Transitional Council is seen to be trying to heal the wounds of the past caused by the divisions. The Darfur question is still unresolved. The latest coup could not have been meant to resolve all these festering problems, including economic crisis, but to restore the Old Guards which could have only cause further spikes in the tribal and social divisions still prevalent in Sudan.

Sudan has been a playground for competing forces and warlords jockeying for State hegemony with interventions from international community at various points in time but without achieving the much-needed peace and stability for the country to develop economically and socially. Sudan has also turned itself into a playbook for both state and non-state actors trying out their ideological hogwash in form of hybrid theories that has never solve any social problem. Sudan was where military Junkers easily transformed or metamorphosed into civilian dictators, becoming albatross unto the soul of the country. Omar Hassan al-Bashir was the longest serving of such dictators having spent three decades in power without anything to show for it in terms of economic dividends, ethnic harmony or political stability – except economic crisis, ethnic bigotries, social conflicts, civil wars and genocides.

The core of the Sudanese crisis was that democracy has never been allowed to take root as the dominant political system of governance. Authoritarian civilian and/or military leadership has been the rule of the political game in Sudan over the decades – not the exception. Authoritarianism has ruined the social fabrics, distorted the political normative values and created an intolerant worldview from religious (Islamic) standpoint. This is the tragedy of modern Sudan, if modernity can ever be ascribed to the country. Sudan is one of the poorest countries in the world today, poverty inflicted on itself by authoritarian leaders such as Omar al-Bashir despite the availability of abundant natural resources that could help transform it into a genuine modern economy and state.

Sudan presents a complex case study in failed modern state. Before the advent of al-Bashir in mid-1989 and after he was overthrown in 2019, Sudan has always been a State in transition with transitional regimes managing the affairs of the State. Democratically-elected leadership which creates at least a modicum of stability and legitimacy has always been a rare commodity in Sudan. In other words, the transitional character of the Sudanese State has always been a feature of Sudanese society since the independence years with the exception of the period of Omar al-Bashir and his venal authoritarianism. However, this transitional character of the Sudanese State can only be fully understood within the broad context and circumstances of VUCA-ed environment which Sudan willfully plunged itself over the years. Sudan has made itself volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous because of the fundamental weakness or fragility of the State itself, the unsavoury character of its ruling clique and its willingness to accommodate all manners of rubbish. This VUCA-ed environment was fed upon extensively by external forces, exploiting it to their own advantages. Sudan has itself to blame and nobody else. As the African proverb says: if there is no crack in the wall lizards and other reptiles cannot penetrate the wall! Sudan because of its peculiar and specific type of volatile politics has allowed its wall to be cracked open. The political landscape has been fracked over a long time to the extent of becoming almost hopelessly impossible to cement the debris together.

Sudanese VUCA-ed environment is also part of a larger regional VUCA-ed environment of East Africa and/or the Horn of Africa – similar to what exist in West Africa and the Maghreb. East Africa/Horn of Africa has also been a largely unstable region for many decades past. No country is spared its own share of instability which fed upon that of other countries in the region. Sudan is partly a victim of a larger unstable region even though it is regarded as the linchpin of the regional instability because of its degree of venality of an evil regime under Omar al-Bashir authoritarian and iron-fisted rule for three decades. It is an inexplicable conundrum as each country compounds the internal problems of one another.

The coup speaks directly to the very character of the Sudanese State: its inherent weakness, fragility or instability which makes it extremely difficult to impose its hegemony on the society in view of the centripetal forces pulling at it from time to time. This is worsened by the fact that Sudan has to operate and maneuver for elbow room within a very troubled region too. But worst of all is the proclivities for anarchy and violence escalated by the various factions or power blocs jockeying to capture the State manifesting in rejection of democratic process but preference for the use of brutal kinetic force of arms. This was the dominant situation throughout the era of Omar al-Bashir, the assimilation of the fundamentalist teachings of Dr. Hassan al-Turabi and the willingness to accommodate Al Qaeda from 1991 to 1996.

The Sudanese crisis is deep-rooted in the Sudanese political and social structures inherited as colonial legacy. The structural crisis of the Sudanese society has not been resolved till date not even with military intervention and rule for many decades since independence. Further research would without doubt yield unexpected wealthy results in terms of details although these details would most probably not alter the fundamental nature of the phenomenon of military intervention in Africa and the role it has played in the modern Sudanese crisis. Sudan provides such a basket-full case of military coups and counter-coups with such amazing details of how a phenomenally unstable and highly fractious country can lend itself to this phenomenon of military interventions. But the absurdity of it all is that these coups and counter-coups only deepen and widen the scope of this instability and fractiousness to the critical juncture or tipping point that had since split the country into two independent sovereign countries: (North) Sudan and South Sudan in 2011.

The tipping point and the split are indeed very profound. They have their historical root in time even before independence of Sudan in 1956. The understanding of this historical perspective is necessary for the present time in which Sudan is still struggling or grappling with its statehood and sovereign identity.

Background

Martin Meredith helps us to capture this historical perspective in his book. Since 1899 Sudan has been run nominally as a condominium, with control shared jointly by Britain and Egypt. In practice it had been ruled by Britain alone. For much of the nineteenth century it had been part of their own empire, conquered by Mohammed Ali’s forces in 1819. Its capital, Khartoum, lying at the confluence of the Blue Nile and the White Nile, had originally been founded as an Egyptian army outpost.31

On 12 February 1953 Sudan was set on the road to independence, scheduled for 1956 after a three-year transitional period. The timing was determined not by any notion of Sudan’s ‘readiness’ for independence but by the exigencies of Britain’s Middle East policy.32

There were inherent dangers in such a pace of change. Sudan was a country of two halves, governed for most of the colonial era by two set of British administrations, one which dealt with the relatively advanced north, the other with the remote and backward provinces of the south. The two halves were different in every way: the north was hot, dry, partly desert, inhabited largely by Arabic-speaking Muslims and containing three-quarters of the country’s population; the south was green, fertile, with high rainfall, populated by diverse black tribes, speaking a multitude of languages, adhering mostly to traditional religions but including a small Christian minority which had graduated from mission schools.33

What links of history were between the north and the south provided a source of friction. In the nineteenth century northern traders had plundered the south in search of slaves and ivory. Tales of the slave trade, passed from one generation to the next in the south sustained a legacy of bitterness and hatred towards northerners which still endured. Northerners, meanwhile, tended to treat southerners as contemptuously as they had done in the past, referring to them as abid – slaves.34

Only in 1946, when ample time seemed to be available, did the British begin the process of integration, hoping that the north and the south would eventually form an equal partnership. From the outset, however, southern politicians expressed fears that northerners, because of their great experience and sophistication, would soon dominate and exploit the south. The south was ill-prepared for self-government. There were no organized political parties there until 1953, nor any sense of national consciousness uniting its disparate tribes. When negotiations over independence for Sudan were conducted in 1953, southerners were neither consulted nor represented. While Sudan’s march towards independence in 1956 was greeted with jubilation by northerners, among southerners it precipitated alarm and apprehension.35

From the above, it is very obvious that Sudan has never really known enough peace in its political life and evolution as a modern state. Indeed, it is difficult to call Sudan a modern state because of the depth and scope of instability that has formed a heavy burden on its soul for many years now. Sudan has rotated between civilian contraptions and authoritarian military regimes, lurching from one crisis to another. The “northern” Sudanese hegemonic posturing against the “southern” Sudanese and insufferable arrogance could only fetch Sudan more trouble than it could manage. The historical hegemony only ended up splitting the country into two in 2011 and the arrogance fetching it more political instability, economic retardation and ethnic rivalries than it hoped for.

This coup attempt can only be understood in the context of historical background or perspective of the long-drawn ethnic divisions, political instability and economic crisis that have been the lot of Sudan since independence. A desultory analysis by taking the coup exclusively as one-off event will not yield any good harvest. The coup must be taken or viewed in the context of historical chain of cause and effect of interweaving factors and forces fighting over control of the soul of Sudan itself. Such a contextual analysis lies at the heart of complexity science needed to fully understand the chain of events that have led to the latest coup attempt.

Military coups and counter-coups have been a pervasive feature of Sudanese political life since independence. But it is also clear that Sudan is divided between those who want to forge ahead with democratic rule and those who want to revert back to military rule. This is the modern dilemma faced by Sudan. Caught in between the crossfires are the innocent citizens who would rather prefer to live in peace and even in their poverties. Whether North or South, Sudanese soil has been tragically watered by bloodletting, with souls of innocent citizens crying to the heavens for justice. Whether these atrocities were carried out in the names of Islam, Christianity or animism nothing justify these killings and destructions that have collectively set the two countries back several years.

The deteriorating relations have put the fragile transition to democratic civilian rule in its most precarious position in the two years since the removal of former President Omar al-Bashir.36

The long uncertain military and civilian partners in Sudan’s transition have traded barbs following the coup attempt on Tuesday by soldiers loyal to Bashir. Generals have accused politicians of alienating the armed forces and failing to govern properly. Civilian officials have accused the military of agitating for a takeover of power.37 In a statement late on Sunday civilian Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok said the dispute “is not between the military and civilians, but between those who believe in the civilian democratic transition either military or civilian, and those who want to block the path from both sides.”38

On Sunday, members of the Committee to Dismantle the June 30, 1989 Regime and Retrieve Public Funds said that they were told in the morning that the military had withdrawn its protection from the committee’s headquarters and 22 of its assets. The soldiers were replaced by police officers, they said.39 The committee, whose purpose is to dismantle the political and financial apparatus of the ousted government, has been criticised by the military generals participating in the transition, who served under Bashir. Mohamed Al-Faki Suleiman, committee leader and member of the joint military-civilian Sovereign Council, Sudan’s highest authority, said his official protection had also been withdrawn.40 Speaking to a large crowd who were chanting pro-revolution and anti-military rule slogans at the committee’s headquarters, Suleiman asked people to be prepared to return to street protests if necessary. “We will defend our government, our people, and the democratic transition to the last drop of blood, and if there is any threat to the democratic transition we will fill the streets and be at the forefront as is our responsibility,” he said.41

In a statement, the Sudanese Professionals Association, the body that helped lead the 2018-2019 uprising that led to Bashir’s removal, called for the end of the partnership with the military. Earlier in the day, sovereign council head General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan said in a speech that the military would not stage a coup against the transition, but remained critical of civilian politicians.42

According to Peter Fabricius of the Institute of Security Studies, in reference to the coup that deposed the Sudanese military strongman, Omar Hassan al-Bashir, “Sudan offers a laboratory for students of the coup. It has had 15 attempts, five of them successful – more than any other country on a continent that has itself seen more coups than any other region of the world. And on 21 July, Sudan made history again by putting its deposed president Omar al-Bashir on trial for leading the 1989 military coup that brought him to power.43

It was a unique moment. This was the first time an African leader was being prosecuted for conducting a coup – or at least a successful one – as far as one can establish.44 There was more than a touch of irony in the event too since al-Bashir himself had been deposed by a coup in April 2019. It was a very different kind of coup, however, from the one that brought him to power.45 Al-Bashir toppled the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi. It had all the trappings of a classic military coup. The army arrested Sudan’s leaders, suspended Parliament, closed the airport and seized the national radio to announce it was in power.46

On the streets of Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, people are breathing a heady mix of fear and hope. Since April 11th, when a cabal of army officers pushed out the 75-year-old Omar al-Bashir, the country’s president for the past 30 years, Sudan has had two more of its bloodied leaders step down. On April 12th, just a day after taking control, Awad Ibn Auf, the defence minister and head of the self-appointed “transitional military council”, resigned. The next day, so did Salah Abdallah Gosh, the head of the much-feared National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS). On April 13th the latest military leader, Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan, announced his intention to “uproot” the military government, prosecute those guilty of killing protesters and reform the NISS. He has promised to hand power over to civilians within two years. The protesters camped outside the defence ministry over the past week have succeeded in changing their country.47

There is one big factor largely overlooked in the analysis of the unfolding event in Sudan. It is the diarchic arrangement or constellation of power currently in Sudan i.e. cohabitation between the civilian and military wings in the highest echelon of power. In reality this may be accepted as valid as a reflection of the critical balance of forces and power-sharing arrangement currently in Sudan. But it is a recipe for instability as both wings jockey for supremacy. The head or chair of the Sovereign Council is General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the Prime Minister is Abdallah Hamdok who is seen as a professional and/or technocrat. There is always overt or covert mutual suspicion even when joint decisions are taken together from time to time in management of state affairs. But it is not known how these decisions are taken, who actually calls the shots within the ruling council.

It is apposite to note that certain elements appointed to the Committee to Dismantle the June 30, 1989 Regime and Retrieve Public Funds have been reported to be wholly unhappy with the exercise. The Committee is actually meant to dismantle the shameful legacy of Omar al-Bashirian authoritarian rule and particularly the corrupt proceeds the regime has stacked up for three decades.

The history of Sudan has largely been that of blood-letting. Over the last ten years, it has been a continuous blood-shedding with thousands of people losing their lives alongside their properties. They were caught as victims in the crossfires between various factions and actors whose interests cannot be defined in terms of national interests but only within the narrow confines of their selfish interests in their Manichean quest to have access to State and the resources it offer. Ultimately, it is a ferocious and internecine struggle to capture the State machine and its pillars of power.

[For instance, t]he Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM), and other groups established the Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF) in opposition to the Sudanese government [headed by Omar Hassan al-Bashir] on November 12, 2011. Some 35 government soldiers were killed by rebels in North Darfur on November 23, 2011. Government troops clashed with SPLM-N rebels in Warni in South Kordofan on December 10, 2011, resulting in the deaths of 19 individuals. Government police clashed with protesters in Khartoum on December 22-30, 2011. Khalil Ibrahim, leader of the JEM, was killed by government troops in North Kordofan on December 25, 2011. Government troops clashed with SPLM-N rebels in the state of Blue Nile beginning on January 20, 2012, resulting in the deaths of seven rebels and 26 government soldiers. SLM rebels killed some 12 government soldiers in the state of North Darfur on February 22, 2012. SRF rebels claimed to have killed up to 130 government soldiers near Lake Obyad in South Kordofan on February 26, 2012. One UNAMID peacekeeping soldier was killed during an ambush in South Darfur on February 29, 2012. On March 1, 2012, the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Defense Minister Abdelrahim Mohamed Hussein for crimes against humanity and war crimes. One UNAMID personnel from Togo was killed during an attack on April 20, 2012. On April 24, 2012, the UN Security Council condemned the attack on the UNAMID.48

JEM rebels attacked a government military camp in northeastern Darfur on June 2, 2012, resulting in the deaths of several government soldiers and 25 rebels. The government released from detention two members of the opposition Popular Congress Party (PCP), Ibrahim al-Sanousi and Ali Shamar, on June 11, 2012. Government police clashed with protesters in Khartoum, Omdurman, and other cities on June 16-29, 2012. Government troops clashed with SPLM-N rebels in South Kordofan on June 21, 2012. Government police clashed with protesters in Khartoum and Omdurman on July 11-16, 2012. Government troops clashed with JEM rebels on July 24, 2012, resulting in the deaths of more than 50 rebels. Government troops clashed with SPLM-N rebels in South Kordofan on July 25, 2012, resulting in the deaths of 46 government soldiers and five rebels. Government police clashed with protesters in Nyala in South Darfur on July 31, 2012, resulting in the deaths of at least six protesters. Ibrahim Gambari completed his duties as Joint AU-UN Mediator for Dafur on July 31, 2012. On July 31, 2012, government police and protesters clashed in Nyala in the state of South Darfur, resulting in the deaths of six protesters. Aïchatou Mindaoudou Souleymane of Niger served as the interim Joint AU-UN Mediator from August 1, 2012 to March 31, 2013.49

SRF rebels ambushed government troops in South Kordofan on August 21, 2012, resulting in the deaths of eleven government soldiers. Government troops clashed with SPLM-N rebels in South Kordofan on August 22, 2012, resulting in the deaths of 17 government soldiers and one rebel. On UNAMID personnel was killed during an attack on a UNAMID police station on August 15, 2012. On August 15, 2012, the UN Security Council condemned the attack. Government troops clashed with SPLM-N rebels in South Kordofan on September 6, 2012, resulting in the deaths of 45 rebels and 21 civilians. Government troops clashed with JEM rebels in North Darfur on September 6, 2012, resulting in the deaths of several government soldiers and 32 rebels. Four UNAMID peacekeeping personnel from Nigeria were killed in an ambush near the town of Geneina in Darfur on October 3, 2012.50

On October 3, 2012, the UN Security Council condemned the killing of UNAMID peacekeeping personnel. Rebels shelled the city of Kadugli in South Kordofan on October 8, 2012, resulting in the deaths of five individuals. Government troops clashed with SRF rebels in South Kordofan on October 14, 2012, resulting in the deaths of 21 government soldiers and seven pro-government militiamen. One UNAMID military personnel from South Africa was killed in an attack on a UNAMID patrol in North Darfur on October 17, 2012. On October 17, 2012, the UN Security Council condemned the attack on UNAMID. SPLM-N rebels killed six government soldiers in South Kordofan on October 22, 2012. SPLM-N rebels killed 30 government soldiers in South Kordofan on October 31, 2012. Government troops clashed with SPLM-N rebels in South Kordofan on November 2, 2012, resulting in the deaths of 70 government soldiers and six rebels. JEM and SLM rebels attacked a military convoy in North Darfur on November 10, 2012. Government police clashed with student protesters at Gezira University in Darfur on December 5, 2012, resulting in the deaths of four students. Government police clashed with student protesters in Khartoum and Omdurman on December 8-11, 2012. SLM rebels attacked a military convoy in North Darfur on December 17, 2012, resulting in the deaths of 18 government soldiers.51

SLM rebels attacked a military base in Jebel Moon in West Darfur on December 18, 2012, resulting in the deaths of more than 20 government soldiers and two rebels. Mohamed ibn Chambas of Ghana was appointed as Head of UNAMID and Joint AU-UN Mediator for Darfur on December 20, 2012. Four UNAMID military personnel were killed in Mukjar in West Darfur on December 21, 2012. Some 30,000 individuals were displaced as a result of violence in the Jebel Marra region of Darfur in late December 2012 and early January 2013. The government claimed to have repelled a SPLM-N attack near al-Hamra in South Kordofan on January 11, 2013, resulting in the deaths of some 50 rebels. Government troops clashed with SPLM-N rebels in South Kordofan on January 13, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 43 government soldiers and eight rebels. Government troops clashes with SPLM-N rebels in South Kordofan on January 19, 2013, resulting in the deaths of four government soldiers and two rebels. Government troops clashed with SLM rebels in Central Darfur on February 6, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 52 government soldiers and 5 rebels. More than 500 individuals were killed in clashes between rival Arab tribes over control of a gold mine near Kabkabiya in North Darfur beginning on January 5, 2013.52

Government troops clashed with SPLM-N rebels in the state of Blue Nile on March 12, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 16 government soldiers and 40 rebels. SLM rebels claimed to have killed some 260 government soldiers during an ambush of government troops near Nyala in South Darfur on March 16, 2013. On March 31, 2013, the military component of UNAMID consisted of 15,213 military personnel (including 14,902 troops and 311 military observers) from 36 countries commanded by Major-General Luther Agwai of Nigeria. The civilian police component of UNAMID consisted of 4,858 civilian police personnel from 34 countries commanded by Police Commissioner Michael Fryer of South Africa. UNAMID included 1,081 international civilian staff personnel. SLM rebels attacked three government military camps in North Darfur on April 9, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 64 government soldiers. SLM rebels captured a government military base in South Darfur on April 14, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 40 government soldiers. Government soldiers clashed with SLM rebels in South Darfur on April 18, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 17 government soldiers. One UNAMID peacekeeping soldiers was killed near Muhajeria in East Darfur on April 19, 2013. On April 23, 2013, representatives of the government and SPLM-N met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia for negotiations mediated by former President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa, representing the AU.53

Government police clashed with protesters near Khartoum on April 26, 2013. Government troops clashed with JEM rebels in North Kordofan on May 25, 2013, resulting in the deaths of several individuals. Rival Arab tribes clashed over agricultural land in Katila in South Darfur on May 28-29, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 64 individuals. Government troops clashed with SLM rebels in South Darfur on June 4, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 46 government soldiers. The National Consensus Forces (NCF), a coalition of opposition groups, called for mass protests against the government on June 8, 2013. Government troops clashed with SLM rebels in Central Darfur on June 10, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 29 government soldiers. Rival Arab tribes clashed over control of a gold mine near El Sireaf in North Darfur on June 26, 2013, resulting in the deaths of at least 40 individuals. Seven UNAMID peacekeeping soldiers, mostly from Tanzania, were killed in South Darfur on July 13, 2013. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon condemned the killing of UNAMID peacekeeping soldiers. JEM rebels attacked a government military base near the town of Jebel al-Dayer on July 24, 2013. Rival Arab tribes clashed in Um Dukhun in South Darfur on July 29, 2013, resulting in the deaths of 134 individuals. President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir announced a cut in fuel subsidies on September 22, 2013.54

Government police clashed with protesters in Khartoum and Omdurman from September 23 to October 11, 2013, resulting in the deaths of more than 200 individuals. First Vice-President Ali Osman Taha was replaced by Lt. General Bakri Hassan Saleh on December 7, 2013. Two UNAMID peacekeeping soldiers were killed near Greida in South Darfur on December 29, 2013. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon condemned the killing of UNAMID peacekeeping soldiers. One student was killed during a demonstration at Khartoum University on March 11, 2014. On March 12, 2014, the U.S. government condemned the Sudanese government for recent violence in the Darfur region. Th Sudanese government sentenced two leaders of the SPLM-N, Malik Agar and Yasir Arman, to death in absentia on March 13, 2014. Government police clashed with student protesters in Khartoum on May 5, 2014. Government police arrested former Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi, leader of the Umma Party (UP), on May 17, 2014. On UNAMID peacekeeping soldier was killed in the village of Kabkabiya in North Darfur on May 24, 2014. One individual was killed during clashes between government police and protesters in Khartoum on June 8, 2014. Government police arrested Ibrahim al-Sheikh, leader of the opposition Sudanese Congress Party (SCP), on June 8, 2014. On June 12, 2014, the U.S. government condemned the Sudanese government for recent attacks against civilians in the state of South Kordofan and Blue Nile. Ibrahim al-Sheikh, leader of the opposition Sudanese Congress Party (SCP), was released from detention by the government on September 15, 2014. An assailant killed two government soldiers guarding a gate at the presidential palace in Khartoum on November 8, 2014.55

The assailant was killed by government soldiers. The seventh round of AU-mediated negotiations between representatives of the government and Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) concerning conflict in the states of South Kordofan and Blue Nile took place in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia on November 12-17, 2014. Peace negotiations mediated by AU mediator, former President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa, resumed in Addis Ababa on November 23, 2014. Some 133 individuals were killed during clashes between the Awlad Omran and Al-Ziyoud groups of the Mesiria tribe in the state of West Kordofan on November 26-27, 2014. Government troops clashed with SRF rebels in South Kordofan on December 2, 2014, resulting in the deaths of 50 rebels. Several anti-government opposition groups, including the Umma Party (UP) and the National Consensus Forces (NCF), signed a “unity agreement” on December 3, 2014. Government security forces arrested Farouk Abu Issa, leader of the NCF, and Amin Mekki, human rights lawyer, on December 6, 2014. AU-mediated peace negotiations held in Addis Ababa ended without an agreement on December 9, 2014. Fatou Bensouda, Chief Prosecutor for the ICC, announced that she had decided to suspend the case against President Omar al-Bashir on December 12, 2014. Legislative elections were held on April 13-16, 2015, and the National Congress (NC) won 323 out of 426 seats in the National Assembly. President Omar al-Bashir was re-elected with 94 percent of the vote on April 16, 2015. Several opposition political parties boycotted the presidential and legislative elections. The AU sent 20 short-term observers from 14 countries led by former President Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria to monitor the presidential and legislative elections from April 10 to April 17, 2015. The presidential and legislative elections were also monitored by the LAS, Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), IGAD, and Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). On June 17, 2016, President Omar al-Bashir declared a comprehensive four-month ceasefire with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) in the states of Blue Nile and South Kordofan, as well as an end to offensive military actions in Darfur.56

On January 16, 2017, President Omar al-Bashir extended the unilateral ceasefire in the states of Blue Nile, South Kordofan, and Darfur by six months. On March 8, 2017, President Omar al-Bashir pardoned 259 rebels who had been captured in fighting with government forces. Members of two Arab tribes in the state of East Darfur clashed in East Darfur on July 22-23, 2017, resulting in the deaths of up to ten individuals. The U.S. government lifted economic sanctions (trade embargo) against the Sudanese government on October 6, 2017. UNAMID consisted of 13,178 troops, 160 military observers, 3,047 civilian police personnel, and 747 international civilian staff personnel on June 30, 2017. UNAMID fatalities included 164 military personnel (163 troops and one military observer), 50 civilian police personnel, and six international civilian staff personnel as of June 30, 2017. Government troops clashed with Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) rebels in Baw District in the state of Blue Nile on December 6, 2017, resulting in the deaths of seven government soldiers. On December 28, 2017, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) faction led by Malik Agar declared a unilateral six-month ceasefire in the state of Blue Nile. On March 28, 2018, President Omar al-Bashir extended the unilateral ceasefire in the states of Blue Nile, South Kordofan, and Darfur for an additional three months.57

The above served as part of the background to the final overthrow of Omar al-Bashir, thus ending his reign of terror of thirty years in April 2019. By the time his reign came to the inglorious end, Sudan has become a lake of blood or put differently its Nile River has become a river of blood. Instead of serving the purpose of rejuvenating life, it became a poison to all who dared to drink from it. Al-Bashir would go to his grave for betraying his people for his vainglorious and megalomaniacal tendencies. He drove his people into the arms of wolves and hyenas, lions and crocodiles. He turned them into pawns in the game of thrones. He made them sacrificial lambs to appease the gods of war fueled by competition for supremacy by various factions within the civilian political class and the military establishment.

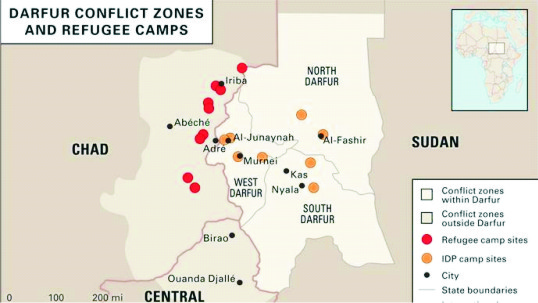

By the time his reign came to an end, Sudan has reached a tipping point or critical juncture from which there was no return; keeled over and split into two. (Northern) Sudan which he was presiding over before he was overthrown was lying prostrate on the ground, battered and torn to pieces by his authoritarian claws. Sudan was again at the tip of complete collapse before it was rescued by the whiskers from his deadly authoritarianism and historic incompetence at managing the political economy. Life has collapsed into Hobbesian state of nature with its nastiness, brutishness, shortness and hopelessness. It has become a killing field exemplified by the heinous activities of Janjaweed and other mercenary hirelings and thugs in Darfur. It was in Darfur that Sudan lost its soul and conscience on account of a Luciferian leader that was Omar al Bashir. The world was horrified but helpless at the spectacle of death in Darfur. Hunger, drought, and disease stalked the land. Aids were not enough to mitigate the human and ecological disaster that became a sort of penalty for cruelty and poor governance to boot. Darfur is the price paid for authoritarianism that was left unchecked for three decades.

The 2019 Sudanese coup d’état took place on the late afternoon of 11 April 2019, when Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir was overthrown by the Sudanese army after popular protests demanded his departure. At that time the army, led by Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf, toppled the government and National Legislature and declared a state of emergency in the country for a period of 3 months, followed by a transitional period of two years before an agreement was reached later.58

Protests have been ongoing in Sudan since 19 December 2018 when a series of demonstrations broke out in several cities due to dramatically rising costs of living and the deterioration of the country’s economy. In January 2019, the protests shifted attention from economic matters to calls of resignation for the long time President of Sudan Omar al-Bashir.59 By February 2019, Bashir had declared the first state of national emergency in twenty years amidst increasing unrest.60

On 11 April, the Sudanese military removed Omar al-Bashir from his position as President of Sudan, dissolved the cabinet and the National Legislature, and announced a three-month state of emergency, to be followed by a two-year transition period. Lt. Gen. Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf, who was both the defense minister of Sudan and the Vice President of Sudan, declared himself the de facto Head of State, announced the suspension of the country’s constitution, and imposed a curfew from 10 pm to 4 am, effectively ordering the dissolution of the ongoing protests. Along with the National Legislature and national government, state governments and legislative councils in Sudan were dissolved as well.61

State media reported that all political prisoners, including anti-Bashir protest leaders, were being released from jail. Al-Bashir’s National Congress Party responded by announcing that they would hold a rally supporting the ousted president. Soldiers also raided the offices of the Islamic Movement, the main ideological wing of the National Congress, in Khartoum.62

On 12 April, the ruling military government agreed to shorten the length of its rule to “as early as a month” and transfer control to a civilian government if negotiations could result in a new government being formed. That evening, Auf stepped down as head of the military council and made Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan, who serves as general inspector of the armed forces, his successor. This came following protests over his decision not to extradite Bashir to the International Criminal Court. The resignation was regarded as a “triumph” by the protestors, who were overjoyed. Burhan is considered to have a cleaner record than the rest of al-Bashir’s generals and is not wanted or implicated for war crimes by any international court. He was one of the generals who had reached out to protesters during their week-long encampment near the military headquarters, meeting with them face to face and listening to their views.63

Despite the imposed curfew, protesters remained on the streets. On 13 April, Burhan announced in his first televised address that the curfew which had been imposed by Auf was now lifted and that an order was issued to complete the release of all prisoners jailed under emergency laws ordered by Bashir. Hours beforehand, members of the ruling military council released a statement to Sudanese television which stated that Burhan had accepted the resignation of intelligence and Security Chief Salah Gosh. Gosh had overseen the crackdown of protestors who opposed al-Bashir. Following these announcements, talks between the protestors and the military to transition to a civilian government officially started.64

In a statement, several Sudanese activists, including those of the Sudanese Professionals Association and the Sudanese Communist Party, denounced the Transitional Military Council as a government of “the same faces and entities that our great people have revolted against”. The activists demanded that power be handed over to a civilian government. On 12 April, Col. General Omar Zein al-Abideen, a member of the Transitional Military Council, announced that the transfer of Sudanese government to civilian rule would take place in “as early as a month if a government is formed” and offered to start talks with protestors to start this transition. On 14 April 2019, it was announced that council had agreed to have the protestors nominate a civilian Prime Minister and have civilians run every Government ministry outside the Defense and Interior Ministries. The same day, military council spokesman Shams El Din Kabbashi Shinto announced that Auf had been removed as Defense Minister and Lt. General Abu Bakr Mustafa was named to succeed Gosh as chief of Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS).65

On 15 April 2019, Shams al-Din Kabbashi announced that “The former ruling National Congress Party (NCP) will not participate in any transitional government”. Despite being barred from the transitional government, the NCP has not been barred from taking part in future elections. Prominent activist Mohammed Naji al-Asam announced that trust was also growing between the military and the protestors following more talks and the release of more political prisoners, despite a poorly organized attempt by the army to disperse the sit-in. It was also announced that the military council was restructuring, which began with the appointments of Colonel General Hashem Abdel Muttalib Ahmed Babakr as army chief of staff and Colonel General Mohamed Othman al-Hussein as deputy chief of staff.66

On 15 April, the African Union gave Sudan 15 days to install a civilian government. If the ruling military council does not comply, Sudan will be suspended as a member of the AU. On 16 April, the military council announced that Burhan had again cooperated with the demands of the protestors and sacked the nation’s three top prosecutors, including chief prosecutor Omar Ahmed Mohamed Abdelsalam, public prosecutor Amer Ibrahim Majid, and deputy public prosecutor Hesham Othman Ibrahim Saleh. The same day, two sources with direct knowledge told CNN that Bashir, his former interior minister Abdelrahim Mohamed Hussein, and Ahmed Haroun, the former head of the ruling party, will be charged with corruption and the death of protesters. On 23 April, the AU agreed to extend the transition deadline from 15 days to three months.67

On 24 April, three members of the Transitional Military Council submitted their resignations. Those who resigned included political committee chair Lieutenant-General Omar Zain al-Abideen, Lieutenant-General Jalal al-Deen al-Sheikh and Lieutenant-General Al-Tayeb Babakr Ali Fadeel. On 27 April, an agreement was reached to form a transitional council made up jointly of civilians and military, though the exact details of the power-sharing arrangement were not yet agreed upon, as both sides wanted to have a majority. The military also announced the resignation of the three military council generals.68

Dozens of women were raped on 3 June 2019 by Sudanese security forces and at least 87 people were killed by Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and other troops tore apart a sit-in camp Khartoum.69

Joseph Tucker gives insights into what might possibly be the motives behind the latest coup attempt.

[T]he Bashir regime [had] installed and nurtured officials across all levels of government and security organs, including at state and local levels. These elements of the previous regime were sidelined and seemingly removed from power by the revolution — but some of these cadres likely remain, despite more senior officials being imprisoned and awaiting trial.70

It is possible that coup plotters that were part of, or sympathetic to, the previous regime want to show continued relevance in the country’s political and military circles. They may also want to engineer a pathway to renewed power. Such sentiments have likely increased due to the historic power shifts ushered in by the transition, and the government will continue to grapple with such dynamics for the rest of the transition and possibly beyond.71

Regardless of who engineered the coup attempt, it reveals Sudan’s competing, disjointed centers of political and security authority and the contested nature of the transition. Sudan’s leaders, both civilian and military, face the unenviable task of trying to reconcile, outmaneuver and/or override these centers while not upending the transition.72

There is recognition that the civilians in Sudan’s transitional government face enormous economic, social and security challenges after decades of conflict and authoritarian rule. Gains have been made to forge peace with some armed groups in war-affected areas, usher in economic reforms and bring Sudan back into international financial folds. Sudanese citizens and international observers acknowledge consistently that the unique civilian-military arrangement resulting from the revolution was perhaps the only solution to preserve citizens’ hard-won gains and provide space for progress.73

Weakening a new civilian political dispensation could have been another motive for the plotters, but if the government’s efforts to bolster civilian political unity and better prioritize the needs of Sudanese citizens proceed, it can show the transformational power of a civilian government as envisioned by the revolution.74

During his remarks after the coup attempt, Prime Minister Hamdok went beyond condemnation to highlight the absence of key transitional institutions, including the long-delayed legislative council, the constitutional court and judicial organs. These bodies will be critical to institutionalizing governance reforms already begun and giving the country a real chance at providing justice to citizens subjected to decades of war and misrule. In the case of the legislative council, its creation is needed to give popular legitimacy and political direction to the transitional government’s decisions and provide space for other political and civic stakeholders to participate. Simply put, the transition will not be complete without these institutions and their absence leaves it vulnerable to events like the attempted coup.75

The central plank of Hamdok’s new political initiative is that reform of Sudan’s security sector and introduction of civilian oversight is key to the transition’s political success. This is recognition of the military’s outsized role in Sudanese politics, conflicts and economics since independence. Such reform, including consensus around a policy that shifts the military’s role from one of regime protection to citizen protection, is the best guarantee that Sudan’s citizen-led revolution will have succeeded in fundamentally changing the nature of the Sudanese state.76

The current Transitional Council was cobbled together in early February 2021 after negotiations with diverse power blocs brokered interestingly by South Sudan. Joseph Tucker further gave insights into the transitional arrangement and what it portends for political stability in Sudan as it move gradually towards democratic rule which is expected to be berthed around 2024.

The announcement on February 8 of a new Cabinet in Khartoum—the product of a peace accord signed by Sudan’s transitional government with several armed groups in October 2020 through a deal brokered by South Sudan—offers hope that the broader inclusion of political leaders can help address Sudan’s pressing challenges and create peace dividends. Unfortunately, the lengthy process of selecting new Cabinet members revealed additional fractures among both signatories to the peace deal and civilian political elements that seemingly offer competing visions for the transition and beyond.77

Twenty-five ministers were announced. All but five ministers were replaced. Only four of the ministers are women. The ministers of defense and interior hail from the security sector as previously agreed between the government’s civilian and military factions. Some posts have gone to high-profile political leaders—for example, Gibril Ibrahim from Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement has been appointed finance minister and Mariam Sadiq al-Mahdi from the Umma Party is the new foreign minister.78

In addition to representatives of groups from Sudan’s peripheries, such as Darfur, South Kordofan, Blue Nile, the east and other areas, the refashioned Cabinet introduces new leaders from the broad yet fragile Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) alliance. The FFC brought together political and civic groups around the 2019 revolution that led to the ouster of former dictator Omar al-Bashir and reached a deal with Sudan’s military to govern the transition. FFC’s members run the political spectrum from leftist politicians and civic and labor leaders to conservative sectarian parties. While this diversity is impressive, it has sometimes resulted in difficulties forming decision-making mechanisms and reaching consensus among alliance members.79

For those ministers representing armed movements, it will be important to build trust with citizens that may view them as closer to Sudan’s security elements than the nonviolent street revolutionaries who ended Bashir’s nearly 30-year grip on power. A way to achieve this is for the Cabinet to begin implementing the complex October 2020 peace deal and ensure that the public understands the agreement’s national impact. Simultaneously implementing the agreement, running a government and continuing to reform the ministries that new ministers will oversee is a tall order. However, effective coordination across ministries—perhaps via a more proactive Ministry of Cabinet Affairs—and transparent decision-making can help.80

It is also important for the Cabinet to have the strong backing of Hamdok and key officials in his office to take unpopular decisions when needed. Some key issues are: unifying exchange rates and continuing to reform subsidies; engaging with military leaders to begin security sector reform that prioritizes citizens’ security; reenergizing negotiations for a more comprehensive peace that includes important armed movements from South Kordofan and Darfur; navigating legitimate demands for transitional justice and accountability; and outlining a foreign policy that defuses regional tensions—especially with Ethiopia and also due to the ongoing Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam negotiations—and reappraises Sudan’s relationship with Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and other Gulf states.81

During Bashir’s National Congress Party era, political and armed actors appointed to Cabinets were often viewed as collaborators with neither independence nor authority. Now, the opposite appears true; current ministers represent several sources of power and some can mobilize constituencies in support of, or against, decisions. It will be imperative for such ministers to indicate that they collectively represent the diverse landscape of Sudanese political, geographic, and social groups. More importantly, they must show through action, not just rhetoric, that such diversity can be harnessed to address the root causes of Sudan’s conflicts.82

Sudan is going through a once-in-a-generation transition that touches every facet of life, from the role of marginalized communities in political decisions to economic choices that will shape the country for decades. Sudanese are creating space to debate issues central to the idea of Sudan as a nation, such as the relationship between religion and the state. Recent months have seen the reentry of Sudan into the community of nations through growing international support for reforms and early efforts to address the country’s staggering debt burden in the wake of the December 2020 removal of Sudan’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism by the United States.83

Sudan faces continued conflict in Darfur, growing political unease in the east and the specter of regional war with Ethiopia. While the armed movements that have signed on to the peace accord have some constituencies, other movements that have yet to reach agreement with the government have significant support in areas like the Nuba Mountains.84

Throughout Sudan’s post-independence history, political parties and armed movements have often been accused of not necessarily representing the interests of communities for which they purport to speak. If the Cabinet can agree on an agenda that prioritizes citizens’ needs, this can build faith in such groups while tempering potentially negative aspects of politics in government. Importantly, the Constitutional Declaration—the transition’s foundational agreement—states that ministers are prohibited from running in the elections planned at the end of the transition.85

A united Cabinet can show that astute political leadership matched with continued reform of government institutions can produce a winning combination for managing diversity and preventing conflict in fragile states like Sudan. The Cabinet’s coherence and its ability to define roles among ministries and publicly articulate an agenda for the transition will be important for the overall functioning of the transitional government. This can also set a foundation for strong engagement with the international community on possible support and mutually accountable partnerships.86

A well-functioning Cabinet can demonstrate to Sudanese that politicians are capable of governing and reduce the perennial unleashing of military coups that have plagued Sudan’s prior civilian governments. However, if leaders carry political conflicts and ideological rivalries with them into the Cabinet, this could decisively imperil an already tenuous transition and restart the cycle of conflict that Sudan and the region can ill afford.87

From the insights provided by Tucker above, it is without doubt evident that Sudan faces the enormous task of restructuring the State machine first to depart from its sordid past history of crimes against the very people it claimed to represent and move towards being responsive and accountable to the people in a symbiotic relationship of mutual trust and to fast-track socio-economic development of Sudan deploying its resources for this purpose.

Reforms of the State machine and its functions form part of the bridge towards bringing different people together towards unity for the purpose of achieving the overall goals of democratic rule and rapid economic development. A key reform I the separation of State and religion, a very difficult task in an Islamic society and more in a country like Sudan where it has unfortunately been the norm but a norm that has proven its deficit beyond all reasonable doubts.

It is also imperative to unite the diverse landscape of Sudanese political, geographic, and social groups into a framework clearly defining national interests that all the diverse groups can key into as a form of social contract. Assurance must be evident that government represents all interests of the diverse groups even if not all the representatives of the groups can be accommodated within a “unity government”.

Above all, the most fundamental task of all is the reform that will lead to loosening the hold of the military on the levers or vectors of power. The much expected reform of the military must have the ultimate aim of subordinating the military to civilian authority. The military has been in power for most of the Sudan’s post-independence life and has clearly bungled the chance of writing its name in gold as the savior of Sudan from its epochal crisis. On the contrary, the military is exclusively responsible for escalating the crisis of Sudanese state and society. It has lost its moral legitimacy to lay claim to power.

Omar al-Bashir, the Authoritarian Grandmaster

The history of “modern” Sudan cannot be written without critical interrogation of the central role played in it by Omar al-Bashir. No other leader than Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, (born January 7, 1944, Hosh Wad Banaqa, Sudan) personify a classic case study of authoritarianism in the modern political life of Sudan. Al-Bashir straddled and bestrode Sudanese political life like a colossus affecting Sudan like no other Sudanese leader. He became Sudanese leader in time of crisis and left it in time of crisis, never achieving peace or progress that could have given Sudan breathing space and take it into the metropolitan centres of comity of nations. It was indeed during his reign that Sudan reached the final tipping point of having to split into two in 2011 when the South Sudan finally broke away. Throughout his reign, Sudan remained on the periphery of metropolitan world both in Africa and the rest of the world.

Conveniently forgetting his humble roots and beginning, al-Bashir grew to become not just a military Junker and a tyrant but a monstrous one for that matter. He became a Medusa to whom human sacrifices are made to appease his blood-mongering authoritarian proclivities and political intransigence. He cuddled terrorists and facilitated global terrorism by harboring well-known terrorism ideologues and jihadists.

Even when oil was later discovered in Sudan, he squandered the oil wealth that came streaming into the national coffer. Sudanese economy was as parlous in its state when he became the Sudanese strongman and when he was finally yanked off power. The available oil wealth was been used to finance the various wars and terrorist escapades and acts of genocides, leaving nothing to improve the oil sector and the economy as a whole. Civil conflicts and wars were promoted and sustained as a way of siphoning oil revenues into private pockets. The net result was increasing poverty, diseases and poor standards of living for the masses of the Sudanese.

Even with his removal, Sudanese economy has not fundamentally improved because he could not manage a modern oil-driven economy. His political obtuseness or intransigence finally led to the splitting of the country in which the breakaway South Sudan took away two-third of the oil wells of Sudan. But it was not just a split on the basis of economic advantage but also on irreconcilable fundamental ethnic, cultural, social and political disagreements between the North and South Sudan as has been aptly described by Martin Meredith already quoted above.88 It was a civilizational clash and parting of ways between two different ideological worlds and worldviews, between Islamism and Christendom. South Sudan was the inevitable that was bound to happen. It was inescapable outcome of the irreconcilable differences between the predominantly Muslim Northern part of Sudan and the largely animist and Christian Southern part of Sudan.

Al-Bashir never blinks his eyes against the fact he was a sworn enemy of Christianity. This is said with all objectivity and without prejudice. He grew up seeing Christianity and the Western world as his twin-enemy. He studied at a military college in Cairo and fought in 1973 with the Egyptian army against Israel and after returning to Sudan and after achieving rapid promotion in the army he took the leading role in the Sudanese army’s campaign against the rebels of the southern Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). After the South Sudan broke away, Al-Bashir shifted his blood-letting focus to Darfur where he finally met his comeuppance through his orchestrated acts of genocide that finally forced the entire world to cry out against him, seeing him for what he truly is and stands for – an evil man – and finally earning him indictments from the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity, genocide, etc.

Under the terms of the 2005 agreement with the southern rebels, a referendum for southern Sudanese citizens was held in January 2011 to determine whether the south would remain part of Sudan or secede. The results overwhelmingly indicated a preference to secede, which occurred on July 9, 2011. The economic fallout from the loss of the south’s oil fields and the ongoing conflict with Sudan’s new neighbour, South Sudan, as well as with rebel groups within Sudan, dominated Bashir’s presidency. Opposition groups and the general public increasingly expressed their dissatisfaction with the NCP’s inability to improve economic conditions, find a peaceful solution to end the rebel activity, or institute constitutional reforms. Bashir’s regime used harsh tactics in an attempt to quell public displays of dissent and to curb the media.89

His chief ideologue was Dr. Hassan al-Turabi, the well-known Muslim extremist and leader of the National Islamic Front (NIF) and advocate of global jihadism against Western world. Al-Turabi was a teacher to Osama bin Laden and together with al-Bashir formed and forged the modern unholy alliance against the Western world particular the United States. Together they began to Islamize the country, and in March 1991 Islamic legal jurisprudence (Sharīʿah) was introduced and imposed helping to widen the division between the Islamic north and the mainly animist and Christian South.

Al-Bashir was not just an authoritarian military Junker but he was equally a thoroughbred modern Machiavellian and Clausewitz to boot. He was able to maneuver and tighten his grip on Sudanese political life for three decades, similar to quite a large number of other African dictators and/or despots. He had been described as a “Spider at the heart of Sudanese web”.90

Born into a farming family in a dusty village 100 miles north of Khartoum, the capital, Mr. al-Bashir served as a paratroop commander in the army. In 1989, he headed an Islamist junta that ousted Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi in a bloodless coup, Sudan’s fourth military takeover since independence in 1956. For the first decade of his rule, though, Mr. al-Bashir, was seen as a front-man for a more powerful force — the cleric Hassan al-Turabi, a smooth-talking, Sorbonne-educated ideologue with sweeping ideas about embedding Shariah law deep in Sudan’s diverse society and institutions.91

International jihadists flocked to Sudan in that period, among them Osama bin Laden, who bought a house in an upmarket Khartoum district and invested in agriculture and construction. In 1993, the United States blacklisted the Bashir government as an international sponsor of terrorism, and it imposed sanctions four years later. In 1999, after a falling-out, Mr. al-Bashir outmaneuvered Mr. al-Turabi and cast him into prison. He turned back to the army to underwrite his authority, forging relationships that spanned the military, the security forces and the country’s tribal leadership.92

Mr. al-Bashir assiduously attended the funerals and weddings of military officers, often sending presents of sugar, tea or dried goods to their families. He held an open house once a week where commissioned officers could drop in and meet with him, said Alex de Waal, a professor at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, and an expert on Sudan. “He’s like the spider at the center of the web — he could pick up on the smallest tremor, [and] then deftly use his personalized political retail skills to manage the politics of the army,” he said.93

Mr. al-Bashir used a similar approach to manage provincial leaders and tribal chiefs, Mr. de Waal added. “Most of them became militarized and enmeshed in one of the popular defense forces. He has that extraordinary network, and it’s all in his head.”94

That style of personalist autocracy was put to use in battling the insurgency in southern Sudan, where rebels from different ethnic groups with Christian or animist beliefs were fighting for independence. During the 21-year war, the Sudanese air force dropped crude barrel bombs over remote villages in the south and sided with vicious local militias recruited by Mr. al-Bashir and his officers.95

At the same time, Sudan discovered oil. After the first barrels were pumped in 1999, living standards gradually rose in one of Africa’s most desperately poor countries. New roads appeared, remote villages gained water and electricity, and shiny buildings rose in Khartoum. “Those were the fat years,” said Magdi el-Gizouli, a fellow at the Rift Valley Institute.96

In 2005, under international pressure, Mr. al-Bashir signed a peace deal with the southern rebels, overcoming opposition from his hard-liners who wanted to keep fighting. But by then another uprising had erupted in western Darfur that would define his legacy. There, a pro-government militia known as the Janjaweed cut a bloody swath through remote villages, quelling an insurgency led by rebels. At least 300,000 people are estimated to have died.97

The unholy alliance struck with Al-Turabi and Osama bin Laden was more poignant and cannot be left out in any analysis of the current impasse in which Sudan today find itself. This unholy alliance still cast its dark pall down to the present time.This unholy alliance was briefly captured by Rohan Gunaratna in his insightful book into the arcane world of Al Qaeda98

Sudan was Al Qaeda’s home from December 1991 to May 1996, a base from which it could seek to extend its influence throughout Africa. Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir and the nation’s spiritual leader, Dr. Hassan al-Turabi steadfastly supported Al Qaeda for many years before they were forced by international pressures, especially sanctions, to expel the group. Although Osama and his cohorts left on a chartered C-130 from Khartoum to Afghanistan on May 18, 1996, the links between the Sudanese regime and Osama continued and the disposition of the Sudanese government to Al Qaeda and Islamists remained unchanged. But in early 2001 the relationship between General Omar al-Bashir and Dr. Hassan al-Turabi deteriorated; al-Bashir got wind of al-Turabi’s plans to oust him and placed him under house arrest. Al-Bashir also secretly approached the Clinton administration with the offer to extradite Osama to the US, but his suggestion was spurned (after 9/11 Clinton admitted that the refusal to accept the offer was his biggest mistake). Seeing the writing on the wall, al-Bashir decided to cooperate fully with the Americans after the 9/11 attacks. Beginning in October 2001 he provided invaluable information to the CIA and European intelligence agencies on Al Qaeda. However, the threat posed by Islamists has not diminished in the Sudan and is likely to resurface from time to time. Parallels are often drawn between Osama and his Sudanese precursor, the Mahdi, who fought a jihad against the British in the late nineteenth century.99

In addition to establishing state-of-the-art training infrastructure, official patronage enabled Al Qaeda to conduct CBRN [chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear] weapons research and runs a weapons shipping network in Sudan. Al Qaeda used the Hilat Koko military facility to test a container of uranium from South Africa purchased for $1.5 million in 1994. This was obtained, via high-ranking Sudanese official intermediaries, by Jamal Fadl, for which he received a $10,000 reward.100