By Alexander Ekemenah, Chief Analyst, NEXTMONEY

The Story

The first “ember” month of the year seems not to be so nice to Guinea. On Sunday September 5, 2021, the elite Special Forces soldiers of the Guinean Army announced that they have toppled the “democratic” government headed by 83-year old President Alpha Conde. Thus, another setback to democratic rule was recorded on the African continent shortly after Chad and Mali followed the same route of coup d’état this year.

In toppling the government of Alpha Conde, the military followed the stock-in-trade chicaneries by not only dissolving the government but also throwing the Constitution of the country into the trash bin, and closed the land and air borders thus trapping the Moroccan [football] team awaiting clearance from their embassy to travel to the airport.

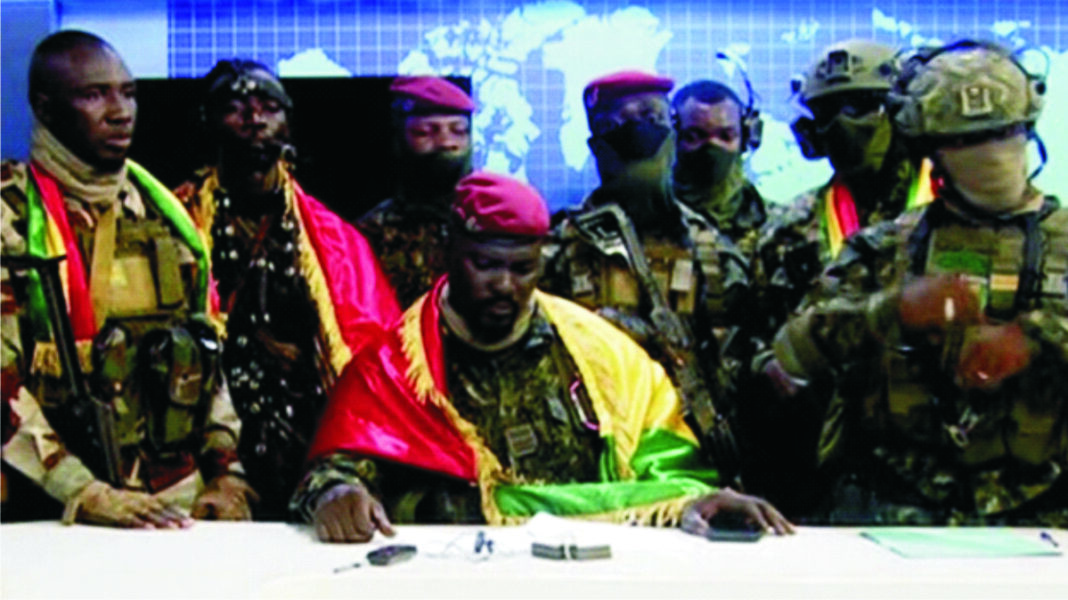

In announcing the take-over, the new head of the military junta, Lt. Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, a former French foreign legionnaire, said on national television that “We have dissolved government and institutions.” “We are going to rewrite a constitution together.”

Draped in Guinea’s national flag, in a kind of symbolic gesture, and surrounded by eight other armed soldiers, Doumbouya said further that “poverty and endemic corruption” had driven his forces to remove President Alpha Conde from office.1

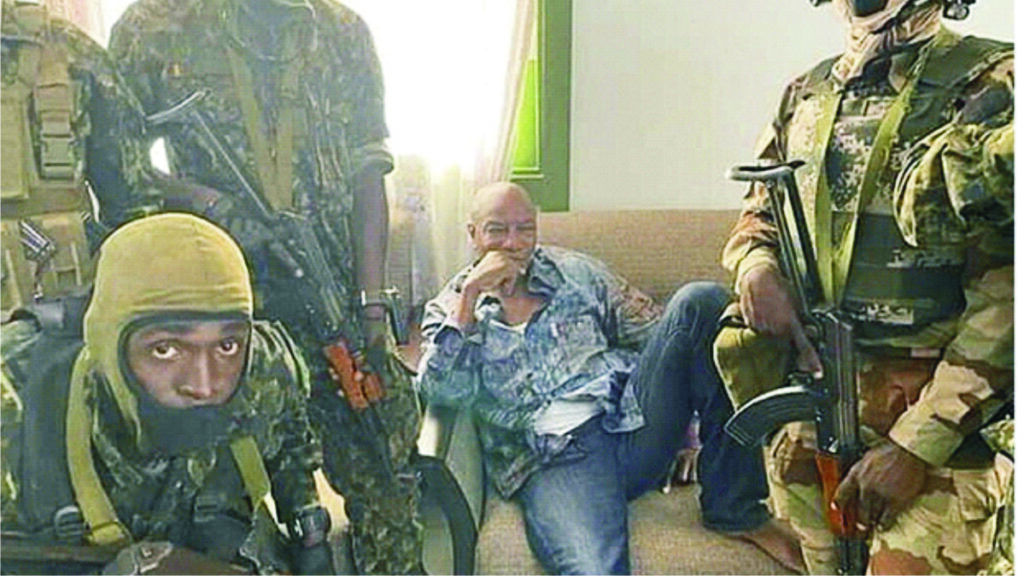

Gunfire [had] erupted near the presidential palace in the capital, Conakry, on Sunday morning. Hours later, videos shared on social media, which Reuters could not immediately authenticate, showed Conde in a room surrounded by Army’s Special Forces.2

Condemnation was not short in coming in cascades.

The United Nations condemned any takeover by force and the West African region’s economic bloc threatened reprisals. United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres said he strongly condemned “any takeover of the government by force” and called for Conde’s immediate release. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) threatened to impose sanctions after what its chairman, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo, called an attempted coup. The African Union said it would meet urgently and take “appropriate measures” while the foreign ministry in Nigeria, the region’s dominant power, called for a return to constitutional order. The U.S. State Department issued a statement headed, “On the military seizure of power in Guinea,” and said: “The United States condemns today’s events in Conakry.” It said violence and any extra-constitutional measures would only erode Guinea’s prospects for peace, stability and prosperity, and added: “These actions could limit the ability of the United States and Guinea’s other international partners to support the country as it navigates a path toward national unity and a brighter future for the Guinean people.”3

Outgoing ministers and heads of institutions were invited to a meeting on Monday morning in parliament, they [the coup engineers] said in a statement read on the state broadcaster. “Any failure to attend will be considered as a rebellion against the CNRD,” the group said referring to its chosen name, the National Rally and Development Committee (CNRD). Guinea’s main opposition leader, Cellou Dalein Diallo, denied rumours that he was among those detained.4

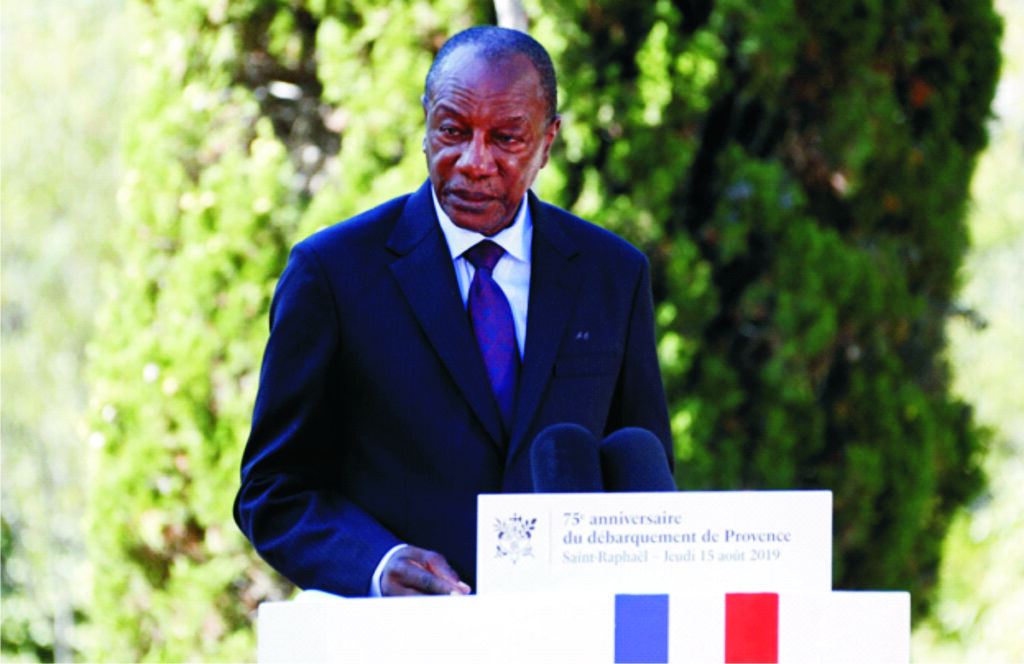

Conde [had] won a third term in October [2020] after changing the constitution to allow him to stand again, triggering violent protests from the opposition. In recent weeks [before the coup] the government has sharply increased taxes to replenish state coffers and raised the price of fuel by 20%, causing widespread frustration.5

Alexis Arieff, at the United States Congressional Research Service, said that, while mutinies and coups were nothing new in West Africa, the region had seen “major democratic backsliding” in recent years. Both Conde and Ivory Coast’s leader have moved the legislative goalposts to extend the clock on their presidencies in the past year, while Mali has experienced two military coups and Chad one. Guinea has seen sustained economic growth during Conde’s decade in power thanks to its bauxite, iron ore, gold and diamond wealth. But few of its citizens have seen the benefits, and critics say his government has used restrictive criminal laws to discourage dissent, while ethnic divisions and endemic graft have sharpened political rivalries. “While the president was proclaiming everywhere that he wanted to govern differently by annihilating corruption, the embezzlement of public funds increased. The new rich were taunting us,” Alassane Diallo, a resident of Conakry, told Reuters. “It is all this that made it easier for the military.”6

The takeover in the West African nation that holds the world’s largest bauxite reserves, an ore used to produce aluminium, sent prices of the metal skyrocketing to a 10-year high on Monday over fears of further supply disruption in the downstream market. There was no indication of such disruption yet.7

Light traffic resumed, and some shops reopened around the main administrative district of Kaloum in Conakry which witnessed heavy gunfire throughout Sunday as the Special Forces battled soldiers loyal to Conde. A military spokesman said on television that land air borders had also been reopened.8 [Nobody could ascertain how many soldiers died in this gun battle]

Regional experts say however that unlike in landlocked Mali where neighbours and partners were able to pressure a junta there after a coup, leverage on the military in Guinea could be limited because it is not landlocked, also because it is not a member of the West African currency union. [Guinea is a member of French CFA group]. Although mineral wealth has fueled economic growth during Conde’s reign, few citizens significantly benefited, contributing to pent-up frustration among millions of jobless youths. Despite an overnight curfew, the headquarters of Conde’s presidential guard was looted by people who made off with rice, cans of oil, air conditioners and mattresses, a Reuters correspondent said.9

In an analysis by Mayeni Jones, BBC West Africa correspondent, the rationales for the coup were called to questioning.

In their televised announcement, the so-called National Committee for Reconciliation and Development made all the right noises. For those frustrated by last year’s constitutional change that allowed President Alpha Condé to run for a third term, news that the constitution would now be scrapped and replaced in consultation with the public has been warmly welcomed. Already there are reports of crowds of opposition supporters and activists taking to the streets of Conakry, to celebrate.10

But military juntas are notoriously fickle. With no one to hold them to account, there’s no guarantee they’ll deliver on their promises. There are also those who worry that this latest coup is further evidence of a gradual degradation of democratic values in the region.11

It’s the fourth attempted coup in West Africa in just over a year. There have been two military takeovers in Mali and a failed attempt in Niger since August 2020. Contested constitutional amendments in Guinea and the Ivory Coast, a region that had been celebrated for a number of peaceful transitions of power in the nineties and early 2000s, appear to be regressing. Ultimately those who’ll pay the price for the erosion of democratic institutions are ordinary West Africans, left without the protections these institutions were meant to provide.12

President Condé was re-elected for a controversial third term in office amid violent protests last year. The veteran opposition leader was first elected in 2010 in the country’s first democratic transfer of power. Despite overseeing some economic progress, he has since been accused of presiding over numerous human rights abuses and harassment of his critics.13

A video emerged hours into the apparent takeover that showed Conde in a room surrounded by Special Forces soldiers, sitting on a coach wearing a wrinkled shirt and jeans. The junta later issued a statement saying the 83-year-old Conde was not harmed and was in contact with his doctors. “We have dissolved government and institutions,” Doumbouya said. “We call our brothers in arms to join the people.”14

Doumbouya cited mismanagement of the government as a reason for his actions. He calls his group of soldiers the National Rally and Development Committee (CNRD). CNRD said on state television later Sunday that all governors had been replaced by military leaders, but that all outgoing ministers were invited to a meeting Monday at parliament.15 France also condemned the “attempted seizure of power by force” and called for Conde’s release, a Foreign Ministry statement said. African Union leaders called on the body’s Peace and Security Council to meet urgently to discuss the situation.16

A Guinean military officer broadcast a statement Sunday announcing that Guinea’s Constitution has been dissolved in an apparent coup. “We will no longer entrust politics to a man. We will entrust it to the people. We come only for that; it is the duty of a soldier, to save the country,” Guinean army officer Mamady Doumbouya says in the video. In a later update that was broadcast on state TV, military officers declared a nationwide curfew and said Conde was unharmed. “We want to reassure the national and international community, the physical and moral integrity of former President (Alpha Conde) is not threatened,” a military officer said, according a translation published by Reuters. “We took all the necessary measures for him to have access to medical care and to be in touch with his physicians.” [But] No clear evidence was provided of Conde’s condition and CNN has not been able to verify the military officer’s claims.17

The officers went on to say that a nationwide curfew had been declared in Guinea. “The curfew is implemented from 8 p.m., nationwide, and this until further notice,” an officer said, reading from a statement. “It is time for us to understand each other, to join hands, to sit down, to write a constitution that is adapted to our realities, capable of solving our problems,” Doumbouya said in the video. Another video circulating on social media showed Guineans cheering military vehicles and waving flags in the capital.18

In a statement published Sunday, the African Union (AU) condemned what it called a “power grab.” AU Chairperson H.E. Felix Tshisekedi and the chairperson of the AU Commission, H.E. Moussa Faki Mahamat, asked for the “immediate release of President Alpha Conde,” according to the statement. United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres also called for Conde’s release, as reports of the apparent coup unfolded. “I am personally following the situation in Guinea very closely. I strongly condemn any takeover of the government by force of the gun and call for the immediate release of President Alpha Conde,” Guterres said in a tweet Sunday.19

Conde won the presidency in 2010, taking control from a military junta that had been in power since 2008. The 2010 presidential elections were the first in the republic’s 52-year history.20

In an exclusive interview with FRANCE 24, the head of Guinea’s elite army unit on Sunday confirmed the country’s president Alpha Condé was being held by his forces. “The president is with us, he’s in a safe place,” said Lieutenant-Colonel Mamady Doumbouya. Guinea’s military Special Forces on Sunday staged a coup, announcing it had arrested the country’s president, dissolved the government and would rewrite the constitution. In an exclusive interview with FRANCE 24’s correspondent Malick Diakité, Doumbouya said: “The whole army is here, from Nzérékoré to Conakry, to help build this country.” He also confirmed that the president was being held by his men. “The president is with us, he’s in a safe place. He’s seen a doctor there’s no problem.”21

Conde, in power for more than a decade, had seen his popularity plummet since he sought a third term last year, saying that term limits did not apply to him. Sunday’s dramatic developments underscored how dissent had mounted within the military as well.22

Doumbouya, who had been the commander of the army’s Special Forces unit, called on other soldiers “to put themselves on the side of the people” and stay in their barracks. The army colonel said he was acting in the best interests of the nation, citing a lack of economic progress by leaders since the country gained independence from France in 1958. “If you see the state of our roads, if you see the state of our hospitals, you realize that after 72 years, it’s time to wake up,” he said. “We have to wake up.”23

Observers, though say the tensions between Guinea’s president and the army colonel stemmed from a recent proposal to cut some military salaries. (Ibid) The developments that followed closely mirrored other military coup d’etats in West Africa: The army colonel and his colleagues seized control of the airwaves, professing their commitment to democratic values and announcing their name: The National Committee for Rally and Development.24

It was a dramatic setback for Guinea, where many had hoped the country had turned the page on military power grabs.25

Conde’s 2010 election victory — the country’s first democratic vote ever — was supposed to be a fresh start for a country that had been mired by decades of corrupt, authoritarian rule and political turmoil. In the years since, though, opponents said Conde too failed to improve the lives of Guineans, most of who live in poverty despite the country’s vast mineral riches of bauxite and gold.26

The year after his first election he narrowly survived an assassination attempt after gunmen surrounded his home overnight and pounded his bedroom with rockets. Rocket-propelled grenades landed inside the compound and one of his bodyguards was killed.27

Violent street demonstrations broke out last year after Conde organized a referendum to modify the constitution. The unrest intensified after he won the October election, and the opposition said dozens were killed during the crisis.28

In neighboring Senegal, which has a large diaspora of Guineans who opposed Conde, news of his political demise was met with relief. “President Alpha Conde deserves to be deposed. He stubbornly tried to run for a third term when he had no right to do so,” said Malick Diallo, a young Guinean shopkeeper in the suburbs of Dakar. “We know that a coup d’état is not good,” said Mamadou Saliou Diallo, another Guinean living in Senegal. “A president must be elected by democratic vote. But we have no choice. We have a president who is too old, who no longer makes Guineans dream and who does not want to leave power.”29

Guinea has had a long history of political instability. In 1984, Lansana Conte took control of the country after the first post-independence leader died. He remained in power for a quarter century until his death in 2008, accused of siphoning off state coffers to enrich his family and friends.30 [It was through a palace coup.]

The country’s second coup soon followed, putting army Capt. Moussa “Dadis” Camara in charge. During his rule, security forces opened fire on demonstrators at a stadium in Conakry who were protesting his plans to run for president. Human rights groups have said more than 150 people were killed and at least 100 women were raped. Camara later went into exile after surviving an assassination attempt, and a transitional government organized the landmark 2010 election won by Conde.31

Two Days after the Coup

The leader of the coup which ousted Guinea’s President Alpha Condé has said a new “union” government would be formed in weeks.32 Col Mamady Doumbouya told ministers who served in Mr. Condé’s government that there would be no witch-hunt against former officials. Col Doumbouya, who heads the army’s Special Forces unit, did not say on Monday when the new government would be in place. “A consultation will be launched to set down the broad parameters of the transition, and then a government of national union will be established to steer the transition,” he said in his statement. He told former ministers that they could not leave the country and had to hand over their official vehicles to the military. He also announced the reopening of land and air borders.33

After the meeting Col Doumbouya drove around the capital, Conakry, which has been tense since Sunday when heavy gunfire was exchanged near the presidential building for several hours. The BBC’s reporter in the city says crowds chanted the military leader’s name. “They were just happy. Some people undressed and shouted ‘Doumbouya, Doumbouya, Doumbouya’ and ‘freedom, freedom, freedom,'” Alhassan Sillah reported. It captures the feeling of many who are relieved that President Condé has been deposed, he said.34

Col Doumbouya also urged mining companies to continue their operations in the country, adding that they would be exempt from the ongoing nationwide curfew. Guinea is one of the world’s biggest suppliers of bauxite, a necessary component of aluminium. Following the coup, prices of aluminium climbed to their highest in more than a decade due to concerns over supplies.35

Mamoudou Nagnalen Barry, a founding member of the opposition National Front for the Defence of the Constitution (FNDC), told the BBC that he had mixed emotions about the coup, but that he mostly welcomed it. “I will say that I’m sadly happy with what happened,” he said. “We don’t want to be happy with a coup, but in certain circumstances like [the ones] in Guinea now, we will say we are really happy with what is happening because without that, the country will be stuck in [the] endless power of one person who wants to stay in power forever.” Mr. Barry added he hoped the soldiers would hand power back to civilians.36

The soldiers who seized power in Guinea during the weekend have consolidated their takeover with the installation of army officers at the top of Guinea’s eight regions and various administrative districts. Coup leader Mamady Doumbouya, a former officer in the French Foreign Legion, has promised a “new era for governance and economic development”. But he has not yet explained exactly what this will entail, or given a timeframe. “The government to be installed will be that of national unity and will ensure this political transition,” he wrote on Twitter on Tuesday.37

In an announcement on Monday evening, the military called on the justice ministry to do what it can to release “political detainees” as soon as possible. Late on Tuesday, about 20 political opponents of Conde were released from detention, AFP news agency reported.38

Public discontent in Guinea had been brewing for months over a flat-lining COVID-hit economy and the leadership of Conde, who became the first democratically elected president in 2010 and was re-elected in 2015. But last year, Conde pushed through a new constitution that allowed him to run for a third term in October 2020. The move sparked mass demonstrations in which dozens of protesters were killed. Conde won the October election but the political opposition maintained the poll was a sham.39

According to analyst Paul Melly from the Chatham House, there are big challenges ahead for the military group. “[Doumbouya] is clearly saying all the right things now about a transition, about an inclusive political approach, reminding people of the need for the reforms, all the governance failures of the past. But the real test is going to lie really in a couple of phases over the next few weeks,” Melly added. “First of all, in his internal discussions, he has got to secure the acquiescence if you like of a broad … political class and civil society in this transition. And although a lot of people are expressing relief … that’s not quite the same thing as signing up for all the details of the new transition. And the next stage will be a difficult negotiation with ECOWAS, the West African bloc of which Guinea is a member and which really has a pretty firm constitutional law that soldiers cannot take long term power by force.”40

Cellou Dalein Diallo, the country’s main opposition leader, also expressed his support for the new military government, in the hope that it will lead to “a peaceful democracy” in the nation of 13 million people. Diallo’s opposition coalition ANAD urged the ruling military to establish “legitimate institutions capable of implementing reforms” and to uphold the rule of law.41

Reporting from Conakry, Al Jazeera’s Ahmed Idris said the military was trying to win the “heart and minds of Guineans, and from indicators, things seem to be going their way”. “It seems that there is less division in the military now, and even in opposition strongholds … people are warming up to the new military leaders,” Idris added.42

The coup, meanwhile, triggered concerns about supplies of bauxite, the main aluminium ore, from Guinea, the world’s second-largest producer. The benchmark aluminium contract on the London Metal Exchange remained near a 10-year high hit on Monday. However, mines have not reported any disruption. State-run Chinese aluminium producer Chalco’s bauxite project in Guinea said it was operating normally. The Australian-listed bauxite and gold exploration firms Lindian Resources and Polymetals Resources also said on Tuesday that their activities were unaffected. The Kremlin said it was closely following the political situation and that it hoped Russian business interests, which include three major bauxite mines and one alumina refinery, would not suffer.43

The coup did not, however, trigger any alarm in the diplomatic circuit. It did not cause any rumbling, any thunder clap and lightning. The Russians, for instance, said they will be watching events as the situation unfold – meaning that they have not seen anything so far to cause them alarm or panic. Ditto the Chinese. It is probably only the United States with semblance of commitment to democratic ideals (but of course not ignoring the fact that Alpha Conde had truncated these same ideals by security a third term in office last year October but not under the watch of the current President of the United States, Joe Biden) that protested the coup in vigorous terms and manner but without any indication that it is even considering imposing any form of sanction for any reason against the coup leaders – which means the coup has not in any way infringed on the vested political, economic or security interests of the United States.

The security situation is even interesting considering the fact of what the United States has invested in the maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea over the years and the Pan Sahel Security Initiative. From all indications the coup has not been seen or interpreted to have impacted negatively on the security interests of the United States as far as Guinea and its latest political blues are concerned.

On the contrary, it is important to note the French cavalier attitude towards the coup. Primarily France did not condemn the coup in a manner that can be interpreted to have rejected the coup on a fundamental ideological ground. It did not condemn the coup on strategic and security grounds too. This is quite understandable and apparent enough from the point of view of French involvement in the Sahel security initiative over the years. In addition is the fact that Guinea was a former French colony and is still a neocolonial outpost.

It has not escaped the attention of closer watchers of French activities in Africa that part of France’s global grand strategy is to protect its vested economic, political and security interests in its former colonies including Guinea at all cost. Of course, this strategy is far-reaching in its scope, outlook and constitute one of its strategic pillars and objectives of France’s contemporary foreign policy. This strategic foreign policy pillar is considered the mainstay of its economic life without which France may not survive independent of its former colonies since they provide the bulk of French modern wealth and power. The implications for the welfare of the former colonies are obvious from this standpoint. They are chained to the chariot of modern French imperialism through all forms of iniquitous bilateral and multilateral arrangement or cooperation with France. It is a modern slavery through peonage from which the former colonies have not been able to free themselves in a new liberation struggle.

The Logics and Implications

There is palpable growing worry in some quarters that Africa might be heading back to military rule, the very cauldron of political instability, economic stagnation and domestic insecurity whence it emerged in the last three decades since the collapse of the communist rule in Soviet Union and Eastern European countries.

The end of the Cold War or the Fall of the Iron Curtain/Berlin Wall ushered in a new lease of life for many African countries berthed by the fresh wave of pro-democracy movements that blew across the continent – countries that have hitherto been languishing under suffocating military rule.

In the last one year, however, there have been coups in Mali, Niger, Chad and Mali again. With the latest coup in Guinea, the worry has legitimately increased.

On August 18, 2020, elements of the Malian Armed Forces staged a mutiny. Soldiers on pick-up trucks stormed the Soundiata military base in the town of Kati, where gunfire was exchanged before weapons were distributed from the armory and senior officers arrested. Tanks and armoured vehicles were seen on the town’s streets, as well as military trucks heading for the capital, Bamako. The soldiers detained several government officials including President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, who resigned and dissolved the government. This was the country’s second coup in less than 10 years, following the 2012 coup d’état.44 The coup was led by Colonel Assimi Goita. In a transitional team, Assimi Goita was made the Vice President.

There was also a coup attempt in Niger Republic on March 31, 2021. The coup attempt occurred two days before the inauguration of president-elect Mohamed Bazoum.

The coup attempt was staged by elements within the military, and was attributed to an Air Force unit based in the area of the Niamey Airport. The alleged leader of the plot was Captain Sani Saley Gourouza, who was in charge of security at the unit’s base. After the coup attempt was foiled, the perpetrators were arrested.45

The coup attempt took place while Niger was mired in the War in the Sahel, with marked terrorism and inter-ethnic violence, with the Sahel countries receiving France’s help against terrorists via Operation Barkhane. In particular, there was the massacre in Tilia, where jihadist groups caused 137 deaths in a village in western Niger, a little over a week before the coup. In addition, the coup d’état occurs during a peaceful transition between two democratically elected presidents, a context unprecedented in Niger. The swearing-in of the new president Mohamed Bazoum would occur two days after the attempted coup. However, the defeated opponent and ex-president Mahamane Ousmane contested the election results and lodged a legal appeal with the constitutional court, which was rejected.46

According to Cyril Payen of France 24, “heavy weapon fire was heard for half an hour in the area of the presidential palace. But the Presidential Guard repelled this attack and the situation seems to have come under control”, and the noise of the fighting woke up locals around 3am (local time). The majority of the perpetrators were arrested by the government but some, including the leader of the coup Sani Saley Gourouza, are still at large.47

Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari described the act as “naive and old-fashioned”. The President of the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States condemned the attempted coup, a sentiment which was also echoed by other African countries, including Chad and Algeria.48

The failed coup in Niger was followed by another palace coup in Chad Republic on April 21, less than a month after that of Niger. The Chadian coup was carried by General Mahamat Deby Itno, the son of President Idriss Deby Itno, following his death from gunshot injuries sustained the previous day at the battlefield while fighting the rebels opposed to his regime. Cabinet and Parliament were dissolved. The Constitution was thrown overboard.

Then on May 24, 2021, another coup occurred in Mali which ushered in Colonel Assimi Goita now as a de facto leader of the country.

Should the recent successful three coup d’états (in Chad, Mali and now Guinea) with the failed one (in Niger) be considered as mere drops of water in a fry pan or should they be considered as an ominous warning of the threatening dangers to democratic rule in Africa in the coming decades? Should the military interventions be regarded as necessity to prevent the countries from further sliding down the slope of chaos into state failure?

These are some of the difficult questions begging for answers. These answers lie within philosophical and objective realms. Even though there are significant differences in each of these countries, there are similarities. It is these similarities that are perhaps raising eyebrows in strategic quarters as regards the survivability of democratic rule in Africa in the long run. Alexander Ekemenah had earlier adopted a “funnel approach” to studying what was being suspected as the gradual returns of the generals into the realm of governance at the summit level of the State. His brief study attempted to capture the “decades-long condition in the Sahel region” which has recently witnessed military intervention or return of the Generals in Chad and Mali and which also include a failed attempt in Niger (the latter not captured in his analysis then).49

He noted that rule of law, good governance; public accountability and transparency are strategic in achieving such political stability and not to see them as not been sufficient or effective enough. There is no other way. It is precisely lack of rule of law, good governance, public accountability and transparency that has stalled African development. The impunities of African leadership must stop.50 However, it is precisely the lack of rule of law, good governance, public accountability and transparency that are summarily responsible for the increasing chaotic political, social and economic situation that has come to serve as the raison de’tre for military interventions and returns of the Generals that are now being gradually witnessed even when the militaries themselves do not have monopoly of knowledge to correct all the observed ills and lacunas in governance terrain.

While condemnation of the coup in principle is generally justifiable and acceptable as a norm, it must, however, be understood in the context of the growing political crisis in Guinea that has been surging beneath the surface in the last one year since President Alpha Conde won and secured his controversial third term in office after amending the Constitution through a referendum to pave way for his third term ambition at his old age when he was expected to have retired honourably and become an elder statesman.

At 83, Alpha Conde is one of the oldest leaders in Africa – in the league of Cameroonian Paul Biya and Nigerian Muhammadu Buhari, precisely those countries that are considered not doing well enough politically, economically and strategically to meet the basic international standards of democratic rule. There is no doubt that Conde was “democratically” elected but under questionable circumstances in October 2020 after altering or amending the Constitution to enable him contest that election for a third term in office. Thus one cannot but wonder exactly what Conde think he still have to offer Guineans in terms of economic development, political stability, good governance that he could not deliver in his first two terms of eight years in office.

Conde can thus be seen as his own political grave digger by refusing to leave office peacefully when the ovation was loudest, when his constitutionally eligible two terms of office ended last year. He thus stoked the embers and forces of opposition against himself by elongating his tenure in power through a third term which he secured in not-so-free-and-fair election. It is just a question of time before his cup filled up spilling over and getting drowned in the spillage. He was consumed by the embers of fire that he himself has kindled. He got himself disgraced from power and that stigma would follow him to his grave.

At 83, one wonders what he was still looking for in power or what he thinks he can still do. He could have honourably retired from politics to become an elder statesman or father of the nation – rather than think he has the monopoly of divine knowledge to rule Guinea for as long as he wanted in a fast-pace moving and dynamic global and regional environments. He became evidently power-drunk with swollen head thinking that he already has the military in his pocket, that he cannot be thrown out like garbage by middle-ranking military officers, which was what eventually happened to him. It was buffoonery of the highest order borne out of old-age disease of wanting to play God to become an autocrat, playing to the same time-worn gallery of destructive “I am-larger-than-life” mental disorder.

Guinea has thus boxed itself into a political cul-de-sac, sandwiched between confluence of factors and forces that crisscross each other: a growing authoritarian tendencies by Alpha Conde-led civilian administration as manifested in gross abuse of human rights, detention without trial of opposition figures, slowed economic growth and low standard of living for average Guinean, the growing opposition as manifested by hostile public environment to the government, and finally the unannounced power struggle as a result of febrile relationship between the Conde-led civilian government and the military.

The international community was quick to condemn the coup. In principle, this is in order and may not be challenged. But in practice, Guinea was already sliding on a downward slope through the growing iron fist of Alpha Conde, economic mismanagement and growing social discontent. The international community did not caution Alpha Conde, to tell or warn him of the dangers of going the authoritarian route, of course, under the pretext of non-interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign independent nation. However, looking critically at the content of their votaries of condemnation of the coup, one can easily read between the lines that they only care about the life of Alpha Conde and not the people that have been condemned to live in poverty through his shortsighted economic policies and repressive stance or those who have even lost their lives. The duplicity of the international community may be questioned here: is it not better for one man to be thrown out of power loop because of his own incompetence and/or growing authoritarianism which negate the rule of law than for the whole nation to perish?

Indeed, several philosophical questions emerge for consideration. Should the international community continue to regard a government that changed the Constitution of a country to suit its own selfish purpose a legitimate democratic government? Can a government that has elongated its stay in power beyond the previously Constitutionally-stipulated terms in office be regarded a legitimate democratic government? Should the international community consisting mainly of democratically-elected governments be seeing to be cavorting and sympathizing with another country whose President has altered the Constitution to stay longer in power than necessary? These are very salient questions that must be answer by international relations scholar.

However, as much as military intervention in politics is condemnable and is being increasingly discredited and consigned to the dustbin of history, Guinea presents a case study of doctrine of necessity as the main driver of the military coup in the face of the growing socio-political crisis in that country. While this author is never a supporter of any military coup (in adherence to the maxim: the worst civilian government is better than the best military government), one would like to see and understand the circumstances which brought about the coup. Guinea faces desperate times in which desperate measures have become inevitable. It is this reality of inevitability that has ameliorated the stance of this author and argues that Guinea cannot continue with Alpha Conde with his obviously shabby governance record.

At a regional level, the coup in Guinea may have followed domino effects of previous military coups in West Africa in recent time. In Mali, Colonel Assimi Goita led a coup that swept out President Boubacar Keita, followed by a coup attempt in neighbouring Niger on March 31, 2021.

On April 20, 2021, President Idris Deby Itno of Chad died as a result of gunshot wounds sustained at the warfront while fighting against the rebels opposed to his regime. In a jiffy, instead of following the Constitutional order of succession, there was a palace coup led by his son, General Mahamat Deby Itno, who then sacked the existing political regime, dissolved the Parliament, and threw the Constitution into the dustbin – not without the visible moral support of Nigeria that could not offer any form of resistance to the daylight political heist by General Mahamat Deby Itno.51 Nigeria was the first country to be visited by the new Head of States.

The following month, on May 24, 2021, to be precise, the Malian military also struck in its own fashion leading to the arrest, detention and forced resignation of the government led by President Bah N’Daw and Prime Minister Moctar Ouane, including the Defence Minister, Souleymane Doucoure. The coup was led by Colonel Assimi Goita, also a French-trained Legionnaire, who was the Vice President in the transition cabinet.52 The international community including ECOWAS, AU, EU, UN and several foreign governments cried foul over the Malian coup. But the military junta dug in its heel in power and no amount of sanctions have been able to remove the junta from power so far. It is a fait accompli.

It is interesting to note that the two countries that have recently succumbed to military coups are all former French colonies, including Niger where a coup attempt failed. Guinea’s northern neighbour is no other than Mali where a coup had taken place four months ago, on May 24, 2021, to be precise. Guinea is also a former French colony. Is there or could there be a thread running through all these coups?

From all indications, the military coup in Guinea seemed to have been amplified by the success of coups in Chad and Mali. It seems to have also enjoyed popular support from the masses. What this actually meant is that the coup has social basis in the growing disenchantment and hostility towards Alpha Conde-led government. The time was evidently ripe for the coup and Alpha Conde paid the costly price of being humiliated out of power. His picture and video widely circulated on social media showing being held in a room, barefooted, disheveled and surrounded by leering soldiers not loyal to his command and control any more sums up this humiliation. It was a dénouement in his twilight years – a denouement ostensibly caused by his gross stupidity to contest for a third term in office, a stupidity that broke his camel’s back, and an irreversible decision that sealed his political fate. Fate has dealt him a deadly blow unexpectedly. The Special Forces of the Guinean Army became his deux ex machina to which he was made a sacrificial lamb for his epochal incompetence and intransigence – a syncretic brew of deadly political disease.

Philosophically, the coup may be considered as part of the ebb and flow in the tidal wave of Guinean life. It can actually be considered a breathing space, albeit a temporary sigh of relief in the turbulent and/or surging “Atlantic” ocean or Gulf of Guinean political life. It is definitely not a permanent relief as the military will inevitably have to clear a new path to a more enduring democratic era freed of all unscrupulous political shenanigans.

The central point of the whole incident is that it is military coup of this typology that a country [in West Africa] gets when one messes up the opportunity given to one on platter of gold. Alpha Conde stretched his political luck too far and humiliation out of power was the inevitable result of the mess-up. Alpha Conde threw himself under the bus because he was a bad driver!

Guinea has tragically suffered from authoritarian military rule over 60-year of its post-colonial or post-independence life. It is precisely what has set back Guinea in the comity of West African countries, almost turning it into a basket case. Tragically too, democratic rule under Alfa Conde that was cobbled together ten years ago has turned into a nightmare, thus deepening the crisis of Guinean State and political life. It is a huge burden borne by ordinary Guineans who have never experienced peace and enjoyed spectacular economic prosperity or progress or the proverbial democratic dividends.

It also interesting to note that Guinea was the first former French colonies to repudiate French imperialism, its abhorrent and despicable cultural assimilation policy. France had ravaged and raped its former colonies economically; emasculate them politically; and brainwash them (Leopold Sedar Senghor of Senegal and Felix Houphouet-Boigny of Cote d’Ivoire) before they could manage to wriggle out of French stranglehold in the late 50s and early 60s. The repudiation was led by Ahmed Sekou Toure, one of the great Pan-African leaders during the colonial and immediate post-colonial eras. Martin Meredith captured some of the tragedies of African countries in his book.53

Every military coup has always come with bags full of promises, of celestial peace and an El Dorado of economic development or prosperity that is mutually inclusive. But none of these promises has ever materialized or been fulfilled faithfully. Indeed, military juntas have often transformed into hybrid civilian authoritarian regimes or dictatorships often plunging their countries into more miseries, civil unrest, conflict or war.

The new military junta in Guinea has come with heavenly and earthly promises to win the hearts and minds of ordinary Guineans to its side – Guineans who are eager for a fresh breeze from the increasingly suffocating environment under Alfa Conde hiding under the veneer of democratic rule. But nobody can vouchsafe the military junta delivering on its promises in the final analysis. Everything rests on hope! The new junta no doubt enjoys what seems to be a popular support. But the same people that shouted hosannas yesterday can turn around to cry “crucify him” tomorrow.

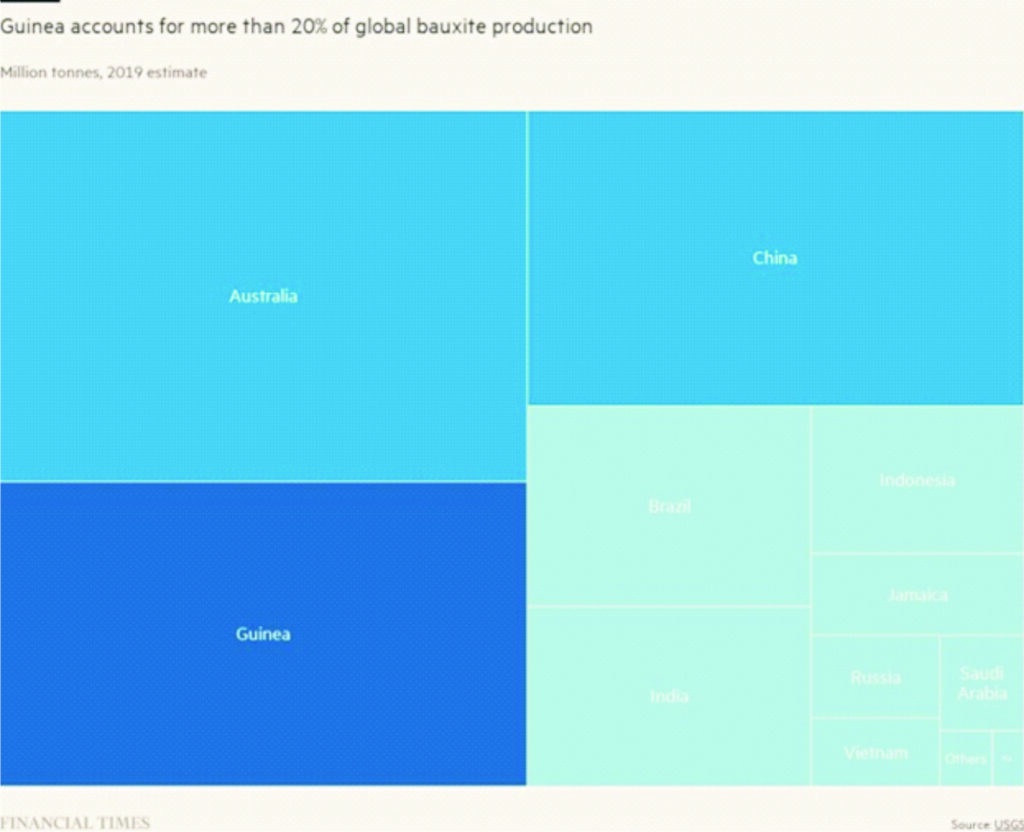

Where is Colonel Mamady Doumbouya Coming From?

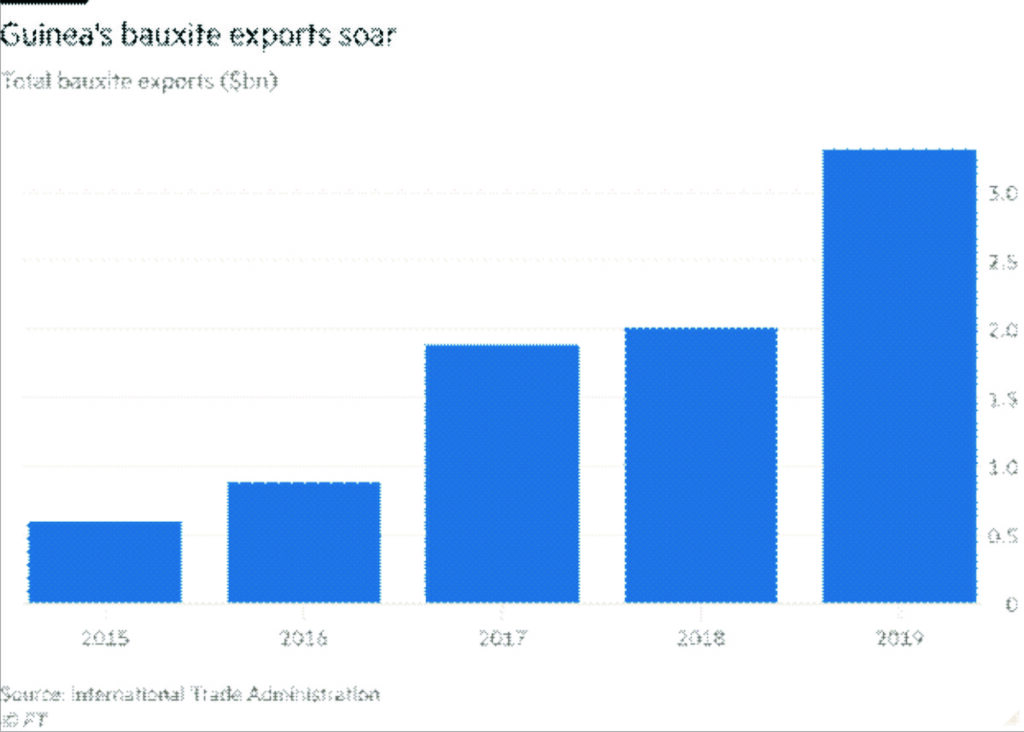

From what can be gleaned from media reports so far, Colonel Mamady Doumbouya is said to be a 41-year old charismatic soldier, a former French Legionnaire and trained as a Special Forces soldier. He is the second youngest Africa leader, after Colonel Assimi Goita, the Malian military leader, who is just 38. Interestingly too, Doumbouya who is married to a French national, hails from the Malinké community, like the deposed president, and hails from Guinea’s eastern Kankan region.

Until the coup, according to reports, he kept a low public profile, with the BBC’s Guinea reporter, Alhassan Sillah, saying he saw him at an event only once – three years ago, when the former French colony celebrated 60 years of independence. “He was the stand-out man because of his physique, height, and dark shades. He led the parade, saluting heads of state and the crowd. Everyone was taking photographs of him, and cheering him – just as they have been cheering him now.”54

By other accounts Col Doumbouya is a brilliant commander, while others say his credentials are dubious. Notably, Col Doumbouya is among 25 Guinean officials the EU has been threatening to sanction for alleged human rights abuses committed in recent years under President Condé.

But after the takeover, he told the nation “we will learn from all the mistakes we have committed and all Guineans”. Ostensibly justifying the coup, Col Doumbouya was reported to have quoted the late Jerry Rawlings – another charismatic soldier who seized power in a coup in Ghana in 1979 – saying: “If the people are crushed by their elites, it is up to the army to give the people their freedom.”55

West Africa political analyst Paul Melly says that Col Doumbouya is just the latest of many middle-ranking officers to lead a putsch in the region, with a promise to bring about political reforms. “But what differentiates him from many predecessors is his international experience, having not only trained in France but actually served in the French military and also in peacekeeping missions or international interventions in a range of crisis-afflicted countries,” he adds.56

During his 15-year military career, Col Doumbouya served in missions in Afghanistan, Ivory Coast, Djibouti, Central African Republic and close protection in Israel, Cyprus, the UK and Guinea. He is said to have “brilliantly completed” the operational protection specialist training at the International Security Academy in Israel, as well as elite military training in Senegal, Gabon, and France.57

After serving in the French foreign legion for several years, Col Doumbouya was asked by Mr. Condé to return to Guinea to lead the newly established elite Special Forces Group (GFS) in 2018. He was then based in Forecariah, western Guinea, where he served under the bureau of territorial surveillance (DST) and the general intelligence services. In recalling Col Doumbouya to set up the GFS, Mr. Condé will have had no idea that he was hastening his own political demise. “I think he [Condé] wanted a security instrument at his disposal for specific repressive missions,” Guinean political analyst Mamadou Aliou Barry told Radio France International. “Unfortunately for him, when he wanted to get his hands on it, the command of the special forces turned against him.”58

Another report has it that he was put in charge of the newly formed SFG elite team – whose remit was to fight terrorism and maritime piracy. He had previously risen to the rank of Master Corporal before being called to command the SFG.59

A graduate from the École de Guerre War College in Paris, he has more than 15 years of military experience that include missions to Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, the Central African Republic, Afghanistan and elsewhere. Doumbouya is an expert in defence management, command and strategy – having also undergone specialist training in Israel, Senegal and Gabon. A spokesperson from Guinea’s Ministry of Defence described him as a “colossus with an impressive physique”.60

The Lieutenant Colonel’s problems with Conakry’s leadership reportedly began when he was prevented from giving the SFG autonomy from the Ministry of Defence.61

There is no doubt that Mamady Doumbouya has an impressive record as a soldier considering his meteoric rise through the ranks to the position of a Lieutenant Colonel or full Colonel (there is no certainty about his rank since the media often report him to be Lieutenant Colonel or Colonel!) within the space of 15 years and having been a commander of an elite unit, the Special Forces Group. He is obviously a recluse but ambitious. He can be seen to have kept his eyes fixed on the political radar screen or crystal ball, watching for the slightest opportunity to strike. That opportunity presented itself on September 5, 2021. It is a date with destiny.

However, there is no evidence to suggest that his impressive record has translated or would translate to managerial capacity to manage a fairly complex society like Guinea and how he would use the vehicle of the State to navigate the rough and tumble politics of international relations with particular reference to the international mining corporations operating in the Guinean mining sector that is the main revenue earner for Guinea and the IMC. As a commander of the SFG, he has not demonstrated any outstanding achievement as a soldier or managed a complex war theatre. He was not the commander of the entire Guinean Army or Armed Forces. Thus his acclaimed professional achievements as a soldier are still very limited considering that he would have had to spend many years rising through the ranks to reach the topmost position in the Guinean Armed Forces.

Judd Devermont, Director of Africa Program at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, while pointing out the Guinean military’s overthrow of President Alpha Condé as an outcome of autocratic overreach, economic mismanagement, and eroding democratic norms including the failure of regional bodies and international partners to anticipate and respond to an evolving coup playbook, noted that since the coup, Doumbouya has twice quoted former Ghanaian coup leader Jerry Rawlings, who infamously publicly executed several of his military predecessors. In a 2017 speech, Doumbouya expressed resentment about U.S and French influence in Guinea.62

As of September 8, Doumbouya and the ruling junta, known as the National Rally and Development Committee (CNRD), have revealed very little about their plans, a troubling sign in a region where young coup leaders have resisted pressure to swiftly hand over power to civilians. The CNRD detained Condé and other top officials, dissolved the government, and imposed a nightly curfew. It has pledged to form a transitional government soon and committed to “rewrite a constitution together.” The junta failed to share additional details on the transition or present a timeline for a return to civilian rule. Doumbouya, however, has paid special attention to the bauxite mining sector, which saw prices leap to a decade high in the wake of the coup. He tried to assure business and economic interests, “asking mining companies to continue their activities” and exempting mining areas from the curfew.63

While Doumbouya’s personal motivations are unclear, Condé’s decision to amend the constitution to run for a third term and recent missteps on the economy set the stage for the military putsch. In his first statement following the coup, Doumbouya vowed that “we will no longer entrust politics to one man; we will entrust it to the people.” He presumably was referring to President Condé’s increasingly messianic leadership. Condé, who had been a longtime opposition leader before his election in 2010, argued that he was the only one who could rule Guinea during a private meeting at CSIS in 2019. Condé proceeded to hold a controversial referendum and problematic election during the pandemic to secure a third term in office. Condé’s move was an affront to the public; according to Afrobarometer polling, more than 8 out of 10 Guineans favor a two-term limit on presidential mandates. Doumbouya also alluded to Condé’s economic mismanagement and the regime’s corruption. He deplored the “state of our roads . . . the state of our hospitals” and said that “we don’t need to rape Guinea anymore, we just need to make love to her.” In another survey, Afrobarometer polling revealed that 63 percent of Guineans believed corruption had increased during the previous year.64

Doumbouya also probably assessed that the region and international community, which had weakly protested Condé’s third term, would do little substantively to oppose the coup, judging from their ham-fisted responses to recent unconstitutional moves in Mali and Chad. The African Union, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), France, and the United States have been hesitant to exact significant penalties in recent years, a contrast to past decades of principled responses to unconstitutional takeovers.65

Devermont is of the view that Doumbouya’s age, temperament, and admiration for the region’s past coup leaders bode poorly for Guinea’s transition to civilian rule. Doumbouya is in the same age cohort as Goïta and Déby, all of whom served in elite military units. Rawlings, Doumbouya’s hero, seized power in a second coup in 1981 before he finally stepped down in 2000. (Goïta visited Rawlings, who recently died, for advice, as well as Moussa Traore, Mali’s military leader from 1968 to 1991.)66

Devermont thinks that Doumbouya and the CNRD probably will use the same coup playbook perfected by Goïta and Déby, parroting the 18-month transition timeline and pledge to rewrite the constitution to placate the international community. If Guinea’s neighbors and external partners quietly accept these conditions, it will serve as a signal to ambitious soldiers in Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, and Niger—to name just a few potential candidates—that there are limited consequences for seizing power. While it is hard to prove a contagion effect, coups d’état in the region tend to occur in waves. Between November 1965 and February 1966, there were military takeovers in Congo, Dahomey, the Central African Republic, Upper Volta, Nigeria, and Ghana.67

Africa’s regional bodies and international partners need to act more decisively to anticipate and respond to this alarming trend and evolving coup playbook.68

Devermont correctly notes that the international community has been meek in responding to problematic elections in Benin, ambivalent in tackling corruption in Mali, and uneven about term limits in Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire. While West Africa has suffered the fastest decline in political rights and civil liberties, its partners have prioritized counterterrorism or strategic competition with China and Russia over democracy promotion. This regression has set the conditions for soldiers to seize power or at least use it as pretext for military action.69

He is also correct to note Africa’s regional bodies and international partners have been going through the motions, instituting temporary suspensions and occasionally levying economic sanctions. These punitive measures usually are lifted quickly either because other priorities are paramount or at the slightest sign of progress. This leniency has enabled coup leaders to make minimal concessions while preparing for longer stays in power.70

The international community has been lulled into accepting an increasingly similar transition plan, including dialogues and 18-month timelines, without questioning the process or objective. In Chad, for example, there is no pressing need to revise the constitution except for the fact that it bars Déby for running for the presidency because of his youth. In Mali, the junta has put forward a transition agenda that is simultaneously expansive and vague, making it difficult to identify priorities or assess progress. Transitions should be fit for purpose, and local, regional, and international stakeholders should help set the various milestones and timelines.71

The growing gap between neighboring countries, regional bodies, and foreign governments, especially ECOWAS, France, and the United States, have enabled authoritarian rulers and coup leaders to forum shop and undercut more forceful responses. President Biden’s Summit for Democracy could start a much-needed discussion on coordination and develop a new repertoire of responses to antidemocratic actions and coups d’état in the region.72

But beyond all the staccato of noise around the coup, could there be something analysts are missing out? For instance, the four countries that have experienced coup d’états recently from Mali to Niger and from Chad and now to Guinea were all former French colonies. Could these coups really have taken place without the prior knowledge of France and its intelligence services including the Foreign Ministry and the individual Embassies in these countries? Is there an unseen puppeteer, a grandmaster, behind the scene pulling the strings? Are we just hearing Jacob’s voice but without feeling Esau’s hand? What are the strategic issues or scenario at stake within the global economic, political and security landscapes that could have drawn France into the vortex of coups in its former colonies at this point in time? Is this part of a grand scenario, a larger picturesque, of neo-imperialist machinations or strike-back, a modern gunboat diplomacy by the former colonial master to repossess its former colonies? Are the military commanders or juntas pawns in this new chess game of gunboat diplomacy by other means?

The tepid condemnation of the coup by individual West African countries including France in this case and ECOWAS as a body is a cause for grave concern. If indeed ECOWAS had been serious about its opposition to military take-over in increasing number in the region in the last few months, it would have mounted sufficient pressure on the military juntas in Chad and Mali to give enough concessions that would guarantee early return to democratic rule in those two countries. But this has not been the case. If France has been sincerely committed to democratic rule in its former colonies, it could have sounded a more alarming note in its condemnation of the string of coups that have taken place so far. But nothing of such has happened thus raising suspicion that the proverbial snake has hands!

The fear is that after some lame protests, ECOWAS countries would go back to mind their own individual businesses, back to the status quo ante or business-as-usual attitude after knee-jerk protests. Indeed many African countries, especially West African countries, are significantly troubled enough by their own internal problems than to pursue a gunboat foreign policy in helping to settle internal problems of other countries that have fallen victims to their own problems. That is why the regional bodies are largely effete. After mouthing some few words of condemnation, there is no political will demonstrated to pursue the matter to logical conclusions. They all go back to sleep, leaving the wolves of military juntas to mind the sheep in other countries. There is no visible ideological opposition to military intervention no matter how bad the situation might have been with the countries.

Real Reasons behind the Coup

It is very doubtful whether anybody saw the coup coming at all, not even intuitively or counter-intuitively. As usual the coup came as a surprise to everybody precisely like the other coups in Chad, Mali and Niger. There was no red flag or blinking light on the screen. There were no harbingers of massive civil unrest to announce the seismic movement or tidal wave of a military coup. There was no popular revolt although there were mild protests after the heist of power through the third term secured by Alpha Conde last year which enabled him to continue in office from October last year. Of course, these protests were met with vicious suppression from the government security forces but without significant protest or challenge from the international community showing acquiescence with the heist of power by Alpha Conde on the part of the international community.

The increasing social and political crisis in Guinea which stem mainly from the increasing authoritarianism of Alpha Conde having secured a third term in office; the corollary increasing abuse of human rights and detention of critics of the government are perhaps enough reasons to spark rebellion from the military which has eventually manifested in the coup carried by the Special Forces Group of the Guinean Army. However, the SFG is probably not closer to the feelings of resentment by the downtrodden Guinean who have been crying out for liberation or even taking to the streets in protests against the authoritarian rule of Alpha Conde than any other Army units.

Another critical factor that must not be overlooked in the contextual circumstances of the coup is the control of the strategic solid mineral resources in that country. In fact, this may be regarded as the linchpin of the coup. Who controls access to the mining fields and who controls the wealth accruable from those minerals? How is the wealth being distributed? Indeed, and interestingly, Guinea has one of the largest deposit of bauxite and other strategic minerals in the world that have attracted giant international mining corporations to the country from America to China. The domain of these strategic solid mineral resources, their extraction, processing and export have become a fierce competitive one for the international mining corporations and foreign governments interested in having access to these minerals. It would not go unnoticed for keen observers that the new military junta did not and have not asked the international mining corporations to leave the mining fields – because that would have automatically cut off State’s access to the royalties and other incomes from the mining sector. There would be chain reaction in which case Guinean foreign accounts could be frozen over a short or long term to be used as a political weapon to arms-twist the new military junta to play ball – if it is actually unwilling to play such a ball.

It cannot, therefore, be ruled out of consideration that this coup may have even been instigated and/or bankrolled by any of these global mining companies – or governments – to edge out rivals from the mining fields and have exclusive access to the minerals. Unfolding events will bear this factor out or refute it.

What can be seen clearly here is that the ambitious Mamady Doumbouya, the commander of the SFG, saw a crack in the wall and was smart enough to capitalize on it to actualize his ambition to become the Head of States. But becoming the Head of States is just a stone-throw to having control of the critical economic structures of the country and not just the vectors of political power. Covered up by the controversies over corruption allegations against Alpha Conde-led government is what can be perceived as the ferocious battle for supremacy or hegemony to control the economic resources of the country and the distribution of wealth accruing from these resources. Unfortunately the critical interrogation of the nexus between these two powerful factors was missing mostly from the reportage encountered in this analysis.

While casual mentions were made to the harsh economic life of Guineans as one of the precipitates of the coup, it did not show precisely how this came to be. While mentions were also made of economic mismanagement under Alpha Conde-led government including controversies over allegations of corrupt practices, these also did link with the rivalries for political supremacy between the civilian and the military or better put among the various power blocs in the country that eventually manifested as the coup. From this perspectival point of view it is indisputable that the Special Forces Group with Colonel Mamady Doumbouya as its commander ostensibly has vested interests in how the Guinean political economy is managed. This is the holistic perspective or bird-eyed view of the coup required to fully understand where the coup came from.

The economy of Guinea indisputably revolves round the mining sector and is the main revenue earner for the country just like oil is the main revenue earner in countries like Nigeria, Angola, Algeria and other African oil-producing countries. In the latter countries, it has become established over a long time that the rivalries and battles for political supremacy among the various ethnic groups and power blocs were the main drivers of the various coups that have taken place in these countries over the decades since their respective individual political independence from their former colonial masters.

The mining industry of Guinea was developed during colonial rule. The minerals extracted consisted of iron, gold, diamond, and bauxite. Guinea ranks first in the world in bauxite reserves and 6th in the extraction of high-grade bauxite, the aluminium ore. The mining industry and exports of mining products accounted for 17% of Guinea’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2010. Mining accounts for over 50% of its exports. The country accounts for 94% of Africa’s mining production of bauxite. The large mineral reserve, which has mostly remained untapped, is of immense interest for international firms. In 2019, the country was the world’s 3rd largest producer of bauxite. Diamond potential is estimated at 40 million carats. In 2012, production was 266,800 carats as per the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, and it is listed as the 13th-largest producer.73

In recent years, the mining industry in Guinea has suffered from controversy, specifically with respect to the iron ore mining industry and the block of mines in Northern Guinea.74

There are two dozen international companies associated with mining operations in Guinea. The domestic agencies involved with mining are the Association pour la recherche et l’Exploitation du Diamant et de l’Or, Friguia Sal, Siguri Gold, and Société AMIG Mining International SARL.75

A major developer in the field of bauxite mining is the Alumina Company of Guinea (ACG-Fria), which is located in Fria; the government of Guinea holds a 49% share while the Reynolds Metals Company holds the 51% balance in this enterprise. Another partner in bauxite mining is Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinée (CBG). It is a joint venture of Alcoa, Rio Tinto, and Dado Mining holding a 51% share, and the Guinean government holding a 49% share. Its exports of bauxite are the largest in the world, reportedly in excess of 13.5 million tonnes in 2008.76

Guinea has large reserves of iron ore with high potential for extraction. These largely remain untapped, and its quality grade is more than 60%. Rio Tinto’s joint sector enterprise in the iron ore sector is the Simandou mine project, with a value estimated at $6 billion. In 2012, Simandou mine was projected to produce 90 million tons of iron ore annually. The Mount Nimba mine, also in the iron ore sector, is located in the Nzérékoré Region, while the Kalia mine is in the Faranah Region.77

A large number of gold mines are located in northeastern Guinea; the estimated production in 2011 was 15,695 kilograms. One of the country’s largest gold mines is the Lefa mine in the Faranah Region. The Kalia Mine is owned by Bellzone Mining.78

In 2008, the government revoked the Rio Tinto licence for the Simandou mine, awarding it instead to BSGR, a company associated with Beny Steinmetz. After the election of President Alpha Condé in 2010, investigations were launched into several allegations of corruption within the mining industry and the government of Guinea expropriated BSGR’s rights to mine at Simandou. But in November 2016, Rio Tinto came under fire for alleged corruption, involving a $10.5 million bribe paid to an aide and close advisor of President Condé to influence him to give the Simandou licence back to Rio Tinto. Rio Tinto admitted making the payment and fired two senior executives. In February 2019, President Condé and BSGR reached an agreement to withdraw the mutual allegations of corruption. The agreement had BSGR relinquish its rights to Simandou and to the smaller Zogota deposit while allowing Niron Metals head Mick Davis to develop Zogota.79

On the sidelines of this affair, Vale filed a claim against BSGR in 2014 at the London Court of International Arbitration to recover an upfront payment it had made to BSGR and money it invested in Guinea. The court decided in favor of Vale and awarded it $2 billion. In May 2020, BSGR filed discovery request documents at the court in New York based on transcripts of conversations with former Vale executives that were obtained by the Black Cube private Intelligence Company. BSGR claims that the documents prove that Vale was aware of potential problems with how the rights to develop Simandou had been obtained, but chose to ignore them and proceeded to buy 51% of the iron-ore licenses. This could undermine Vale’s claims to compensation.80

There have been further corruption allegations levelled at President Condé’s government involving bribery from the U.S. hedge fund Och-Ziff. In August 2016, Samuel Mebiame, who worked for the company, was arrested and charged in the U.S. with bribing Guinean and other African officials on behalf of Och Ziff to receive mining rights and access to secret information. According to the U.S. prosecutors, Mebiame was also part of a conspiracy to form a Guinean state-owned mining company and was involved in rewriting Guinea’s mining code. Mebiame pleaded guilty to conspiring to make corrupt payments to African members of government in December 2016.81

In 2017, Och-Ziff Capital Management Group came under investigation for several instances of bribery in the Guinean mining industry as well as widespread bribery across Africa. In September, a unit of Och-Ziff pled guilty to engaging in a multi-year bribery scheme; the judgement handed down included regulatory sanctions against Och-Ziff founder Daniel Och. In 2018, Michael Cohen, head of Och-Ziff European operations, was charged with ten counts of fraud. This followed a lengthy investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).82

In September 2015, an investigation was launched into Mohamed Alpha Condé, the President’s son. The French Financial Public Prosecutor charged him with embezzling public funds and receiving benefits from French firms that are involved in the Guinean mining industry.83 Another case of alleged corruption in the country’s mining industry is based on the findings of an NGO called Global Witness. According to their report Sable Mining, an AIM-listed company, got close to President Condé prior to the elections and bribed his son in order to receive iron ore mining rights to the Mount Nimba mine. These allegations have been under investigation by Guinean authorities since March 2016.84

In an interesting piece by Financial Times of London, the nexus between the coup and the situation in the mining industry was brought into stark reality for all to see – even though Reuters has similarly made allusion to this as quoted above.

Country became mining powerhouse under ousted leader but people’s lives barely changed. Guinea’s first elected president came to power more than a decade ago promising to stand up to global mining giants and improve the lives of the poor in the resource-rich West African country. But this week, people celebrated on the street as the one-time political exile and democratic activist Alpha Condé was ousted in a military coup. Their charge: Guinea had become a mining powerhouse on his watch but their lives had barely changed. To cap it all, he had tried to extend his rule for a third term.85

Condé in 2010 inherited a dysfunctional state, ruled for decades by Lansana Conté, its mineral wealth exploited in a haphazard fashion and the source of political and legal strife. Over the next decade, he oversaw Guinea’s transition into a major producer, producing a fifth of the world’s bauxite and attracting billions of dollars in investment from China and Russia. “For [the] global aluminium industry, interruptions of bauxite supply from Guinea could have a devastating impact,” said a mining executive. The disruption could be particularly fraught for Russia and China, which rely heavily on Guinean bauxite.86

The explosive growth of the country’s bauxite industry can be traced back to Indonesia’s decision to ban exports of unprocessed minerals in 2014. That forced China’s vast aluminium industry to scour the globe for other sources of supply, eventually settling on Guinea.87

Analysts estimate that about half of China’s bauxite comes from Guinea. Bauxite production soared from 16.3m tonnes in 2015 to 82m tonnes in 2019, according to US geological survey data.88

Bauxite exports rose from $597m in 2015 to $3.3bn in 2019, according to US trade data. Over that period its ranking on the UN’s Human Development Index rose just five slots, from 182 out of 188 countries to 178 out of 189 countries.89

Guinea’s importance to China, its biggest trading partner, was underscored when Beijing, which has a long-held policy of not commenting on the domestic affairs of other countries, issued a rare public rebuke of the coup. And Oleg Deripaska, the founder of Rusal, in a Telegram post warned that “this situation may seriously shake up the aluminium market”.90

The junta, led by Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, a former French legionnaire, understood the [precariousness] of the situation. One of his first steps after taking power — along with plans for a unity transitional government — was to urge mining companies to continue to operate. He said on Monday that ports would remain open for export “to ensure continuity of production”.91

“When the coup happened there was uncertainty,” said Fadi Wazni, an executive with the China-backed SMB Winning consortium that owns Guinea’s biggest bauxite producer and half of the massive Simandou iron ore deposit. “But the first steps [by the military leaders] are providing more comfort.”92

While bauxite is the heart of Guinea’s mining industry today, the future lies in developing the country’s vast reserves of the steelmaking commodity iron ore, including the 2bn-tonne deposit Simandou, the world’s biggest untapped source. Nothing illustrates the fraught nature of the country’s resources than the battle for control of Simandou.93

In 2008, Conté stripped Anglo-Australian miner Rio Tinto of its rights to the northern half of Simandou, handing it to Israeli tycoon Beny Steinmetz’s family’s company, BSG Resources. That sparked a bitter legal dispute that was not resolved until 2019 when Condé took back the rights and awarded them to SMB Winning, which has started work at the site. Steinmetz was sentenced to five years in jail for bribing Conté’s wife in a landmark Swiss corruption trial earlier this year. Steinmetz has said he will appeal against the judgment. “The politicisation of the mining exploitation in Guinea is simply overwhelming and no government from Lansana Conté to [Moussa] Dadis Camara to Alpha Condé, has been able to bring the kind of systematic solution to it, yet that way lies the economic stability of the country,” said David Zounmenou, senior research consultant at the Institute for Security Studies.94

Condé himself has been embroiled in corruption scandals linked to mining. In 2016, the London-based campaigning group Global Witness alleged in a report that the 2010 campaign in which he had pledged to reform the mining sector, was in part bankrolled by corrupt payments. Condé denied allegations in the report that he or his family had ever accepted a bribe.95

Diallo, a leading contender to replace Condé if the junta keeps its promise to transition back to democracy, said he would ask for an audit of all mining contracts because “the impact of mining exploitation is not visible anywhere in Guinea . . . it has [only] enriched the ruling elite”. But he said he would not “come systematically with the idea of cancelling the contract, especially if a company is paying taxes [and] creating jobs”. He added: “We need a judicious mining policy, capable of increasing the added value that the country gets from its natural resources.”96

In Diallo’s words, there are echoes of what Condé once said when he came to power. “I didn’t know him very well, but I knew [him as a] political leader who seemed like a man who in his heart wanted to turn Guinea into a real democracy,” said Cellou Dalein Diallo, the opposition leader who lost to Condé in three elections, which were rife with irregularities. “So I was very disappointed when I saw how he acted because it was the opposite of what I expected.97

“Alpha Condé himself created the crisis that swept him away,” Diallo added. “[He] would not have met such a tragic end” if he had not changed the constitution last year in order to run for a third term.98

What was most poignant about the coup was that there was nothing revolutionary in the outlook of Mamady Doumbouya. Nothing revolutionary can be inferred from his public pronouncements so far. To show that he is not in any way revolutionary inclined and does not intend to pursue any revolutionary ideals or reforms, Doumbouya has left the mining sector in the hands of the same exploitative international mining corporations operating in the country. As at the time of concluding this research article, he has not brought forth any working template of how the mining sector would be restructured and/or drive the new economic growth desired by Guineans that would change their lives for the better. There have been no policy pronouncements on any key issue affecting Guinea.

Fundamentally, the coup did not seem to have altered the balance of forces and power in Guinea in any significant manner. The coup seemed to have been targeted exclusively at President Alpha Conde who was adjudged to becoming more authoritarian after securing third term in office almost a year ago (i.e. October 2020). The coup did not directly sack the Cabinet of Ministers. The coup leaders even specifically requested the Ministers and other high ranking government officials not to “abandon” their duty posts, assuring them of their safety and calling them into a meeting for “negotiation” that will most probably reveal their new roles under military rule.

But the coup so far has not offered any level playing field for any group of political actors as the coup leaders are still meandering in the corridors of power in the presidential palace finding their handles on vectors or levers of power. As at the time of concluding this article in late September 2021 the coup leaders have not come up with any known political agenda that may be interpreted to give a roadmap for the future of Guinea either in the economic, political or foreign policy sector.

The Soldier and the State in Africa: Are the Generals Returning?

For a holistic understanding of the ongoing crisis of democratic rule in Africa vis-a-vis military interventions in the past and the current returning of the Generals, the phenomenon must be properly backgrounded and circumstantially situated and contextualized within each or group of case studies with the specificities and peculiarities of each case clearly outlined – otherwise such analysis would only end up in generalizations which do not do adequate justice to each case study.