By Alexander Ekemenah, Chief Analyst, NEXTMONEY

Introduction

The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine has no doubt run into the murky and shark-infested water of European Union geopolitics within the context of the EU-Brexit controversy of pre-COVID-19 era. In other words, Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine rejection by some European Union countries stemmed out of the unfinished business of Brexit and the vindictive wish to punish the United Kingdom for its peacock arrogance and brash exit from the European Union in which Britain is seen as an outlaw or outcast from the mainstream European continental politics.

Thus the EU geopolitical rejection of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine by several European countries is like a vicious blow to the solar plexus of the British ruling class and its insufferable arrogance. The British did not see it coming at all on the horizon. Why it is more serious, in strategic sense, is because Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is the only major vaccine coming out of the United Kingdom, at least for now. Thus the rejection is not just a reputational damage to the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine brandname but also to the Brits’ pride of place and awareness of its vulgarized position in world affairs. It is a high reputational damage to its diplomatic prowess as the Brits can be seen running from pillar to pole to do damage control. British diplomacy failed this time around to stem the tidal wave of geopolitical tornado or hurricane coming across the English Channel from the main heartland of the European continent. It tells that the Brits may wish to go their own way and the rest of Europe may not care about this. There is an African proverb that says “when a stream decides to leave or cut off from its source, it must be ready to face the consequences of being abandoned to whatever fate it subsequently encounters on its own journey”!

As a result of this snafu, AstraZeneca’s shares on London Stock Exchange fell by 1.5 per cent as far back as late November 2020 even before the crisis snowballed into the huge controversy that it is by mid-March 2021. This is a huge financial loss in an economy that had earlier been battered by the coronavirus pandemic. It is a double jeopardy and major setback for the British bourgeoisie at a time when the world is trying to recover from the negative effects of the coronavirus pandemic. So much goodwill, hope and confidence have been invested in the production of the vaccine – only for all these to be shattered right before everybody’s eyes.

But interestingly while all eyes are fixed on the United Kingdom, AstraZeneca is an Anglo-Swedish pharmaceutical giant. Eyes are inadventently diverted from the role of Sweden in the controversy. Sweden was another sick “man” of Europe during the raging pandemic. Sweden for a long time refused to order lockdown and impose other safety measures in preference for what it called “herd immunity” which at the end of 2020 have seen thousands of Swedes dying like flies. Equally interesting is the fact that Sweden was one of the countries that have so far rejected the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine in a manner akin to Pontius Pilate washing off his hands in denial of whatever sophistries the Brits are putting up in defense of the vaccine!

The only saving grace for the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine has been the developing countries, most especially the former British colonies like Nigeria, countries that can be argued not to care about the explosive controversy because of their legacy hangover of colonial mentality and because of their narrow selfish interests involved with the importation of the vaccine and the concomitant pecuniary gains involved.

In addition to the overall picturesque of this crisis and mess is the involvement and role of University of Oxford which may never be understood, probably for some time to come. Unversity of Oxford is no doubt one of the topmost universities in the world that has earned accolades for its advance researches and intelletual/academic prowess that have push back the boundary of pedestrian ignorance in the world. A team of intrepid Oxford scientists is the originator of the controversial vaccine while AstraZeneca is the manufacturer.

Behind the public scene the British ruling political class is baffled by the sudden turn of unsavoury events in which the Oxford/AstraZeneca is at the epicentre which in turn has led to the United Kingdom being kicked around like football by the EU politics of mortar-and-pestle. United Kingdom is being snubbed left, right, and centre in a way that has not happened probably since the Second World War. United Kingdom is being kicked in the ass, slapped on both cheeks, knocked viciously on the head with a cudgel forcing it to run like a wounded unicorn in the wild!

The world is currently scrambling and stampeding for the available vaccines on the gobal market shelves. With what has happened to Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine, it is highly probable that more revelations will come to the public domain in several other countries on how governments have handled or are handling the coronavirus pandemic and its fallouts. Coronavirus pandemic will generate more controversies than expected in the coming years. The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine controversy is just the tip of the iceberg about the shenaniganisms of governments and private sector operators that have taken place unbeknown to the public. Much will be swept under the carpet. But much will also be revealed to the astonishment of the public and great embarrassment and shame of the main actors whether government officials or business executives.

This article seeks to disambiguate the controversy faced by Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine over the double results obtained while testing for its efficacy.

A Kick to the Groin

The hurricane against the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine came as a gradual build-up into the tsunamic public relations disaster it has become for all the parties concerned: University of Oxford, AstraZeneca company, the British Government, other stakeholders and even the British public.

AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout has gotten off to a rocky start in Europe—to put it mildly. First, a supply shortfall triggered a public back-and-forth between executives and government officials. Then several countries expressed doubts about how well the vaccine works in people over 65. Now seven countries are raising safety concerns.1 Denmark, Norway, Austria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Luxembourg have halted some or all of their AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccinations over fears of blood clots, France24 reports. Previously, Austria had stopped using a single batch of the vaccine after a clotting issue turned up in one recipient. In the wake of the news, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Luxembourg stopped using vaccines from the same batch, France24 reports. Denmark and Norway temporarily stopped all vaccinations with AZ shots, according to the report.2

An AstraZeneca spokesperson said patient safety is the company’s “highest priority.” “Regulators have clear and stringent efficacy and safety standards for the approval of any new medicine, and that includes COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca,” she said. “The safety of the vaccine has been extensively studied in Phase III clinical trials and peer-reviewed data confirms the vaccine has been generally well tolerated.”3

Thursday’s news is only the latest negative development for the rollout of AZ’s product. Since the vaccine’s debut in Europe, public comments from governments, officials and even doctors have raised questions about the vaccine. Germany restricted its use in people 65 and older, citing a lack of data in the age group, and then reversed course. When the shot was initially restricted in her age group, German chancellor Angela Merkel said she doesn’t “belong to the group recommended for AstraZeneca.” Some publications ran with headlines that she’d refused the shot, creating confusion for citizens.4

In January, French President Emmanuel Macron said the vaccine was “quasi-ineffective” in people 65 and older before his country gave the green light in the age group. Adding to all the confusion, thousands of healthcare workers in Europe have refused the shot, Forbes reported last month [February]. They argued they should receive the mRNA vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna.5

The result? Europe’s vaccination program is lagging in other developed countries, as many AstraZeneca shots go unused. As of Thursday, France, Germany, Italy and Poland had used less than half of the AstraZeneca vaccine doses on stock, according to data from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Those countries have received the highest number of doses, followed by Spain, which has used around 60% of its available stock and is pressing ahead with vaccinations.6

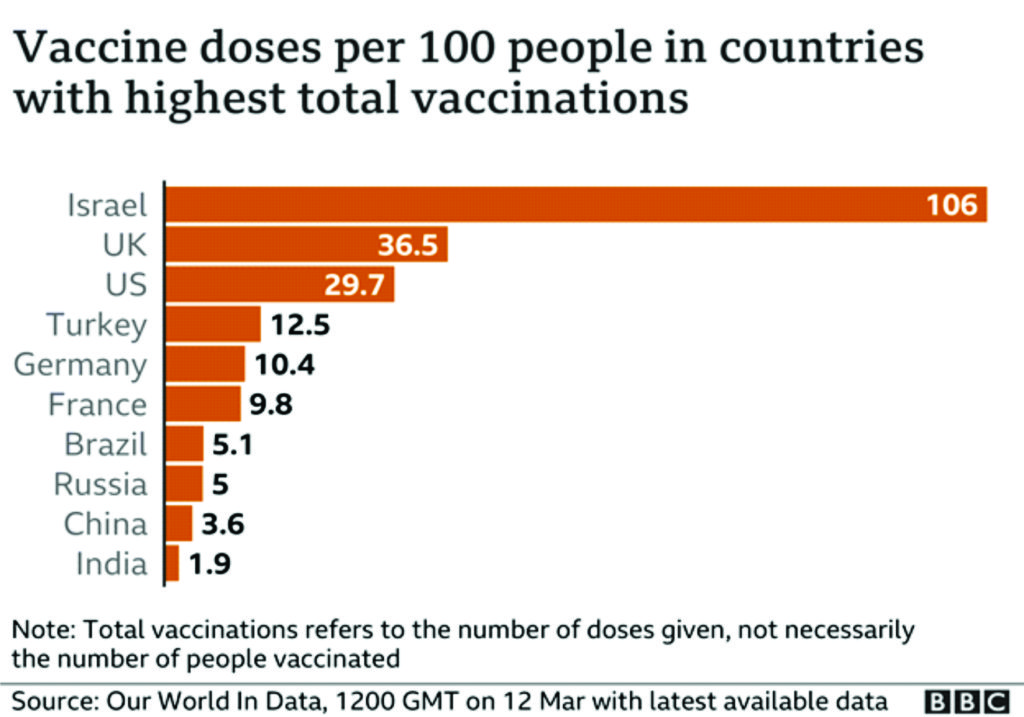

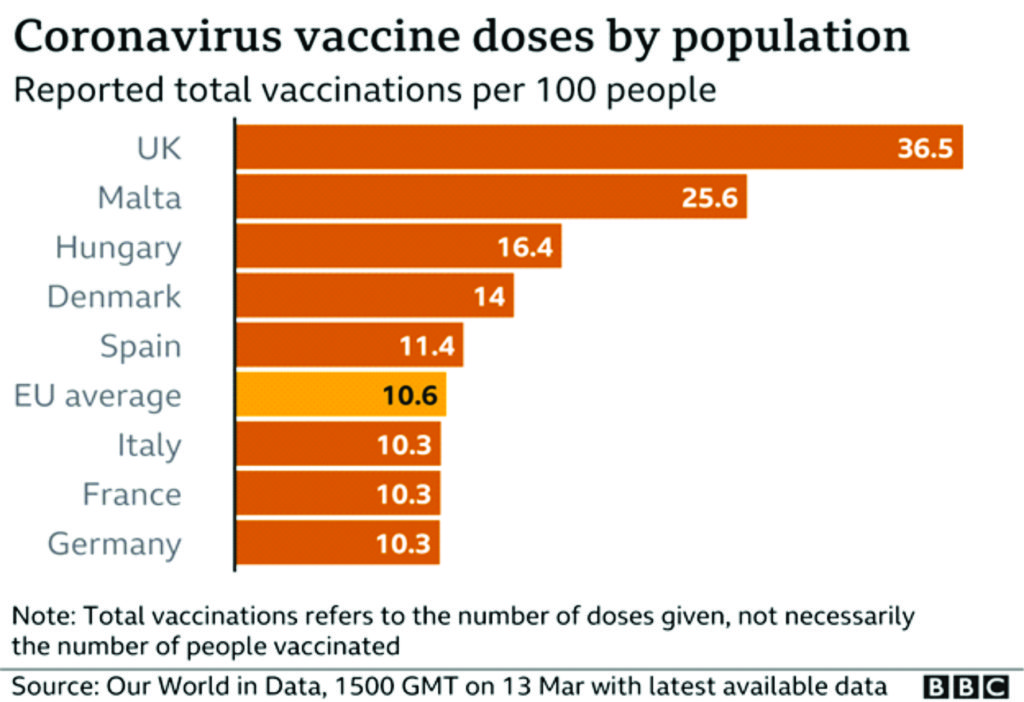

Meanwhile, Europe significantly lags Israel, the UAE, the U.K., Chile and the U.S. in vaccinations given per 100 people, according to Our World In Data.7

[As at March 15, 2021], Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Ireland and the Netherlands have joined the growing list of countries that have suspended the use of the coronavirus vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford over blood clot concerns.8 The Dutch government said Sunday that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine would not be used until at least March 29, while Ireland said earlier in the day that it had temporarily suspended the shot as a precautionary step.9 On Monday, the German government also said it was suspending its use, with the vaccine regulator, the Paul Ehrlich Institute, calling for further investigations. The Italian medicines authority made a similar announcement on Monday afternoon and French President Emmanuel Macron also said the vaccine’s use would be paused pending a verdict from the EU’s regulator. Spain Health Minister Carolina Darias said Monday that the country will halt use of the shot for at least two weeks, Reuters reported, and Portugal and Slovenia also suspended the vaccine.10

[But] the World Health Organization has sought to downplay ongoing safety concerns, saying last week that there is no link between the shot and an increased risk of developing blood clots. The United Nations health agency has urged nations to continue using the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine.11 Despite this, a number of European countries have already paused the use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. It has added to the woes of the region’s ailing vaccination campaign at a time when Germany’s public health agency has warned that a third wave infections has already begun.12 Thailand [far away from continental Europe] has also halted its planned deployment of the vaccine.13

The move to pause its use by Dutch and Irish officials came shortly after Norway’s medicines agency said it had been notified of three health workers being treated in hospital for bleeding, blood clots and a low count of blood platelets after receiving the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. Norway has put its Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine program on hold.14 Geir Bukholm, director of the division of infection control and environmental health at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, said Norway’s medicines agency would “follow up on these suspected side effects and take the necessary measures in this serious situation.”15

Europe’s drug regulator, the European Medicines Agency, has said there is no indication that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is causing blood clots, adding that it believes the vaccine’s benefits “continue to outweigh its risks.” The EMA acknowledged some European countries had paused the use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca shot but said inoculations may continue to be administered while an investigation of blood clot cases is ongoing.16

Irish Prime Minister Micheal Martin told CNBC on Monday that he anticipated the pause would be temporary and the country was aiming to catch up quickly with its inoculation program. “There is no causal effect established or anything like that yet, but as a precautionary move in line with the precautionary principle and in an abundance of caution, our clinical advice was to pause the program whilst the EMA does a review of this,” he said. “This is an unwelcome pause but nevertheless I think it’s important that we take heed of the advice we have received.”17

In far-away Thailand, another hurricane was brewing.

Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha became the first person to be inoculated with the AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine in the Southeast Asian country on Tuesday after the rollout had been temporarily put on hold over safety concerns.18

Prayuth and other cabinet members had been initially due to get their vaccine shots on Friday, before Thailand suspended the use of the AstraZeneca vaccine after reports it could cause blood clots prompted a number of European countries to hit pause. “Today I’m boosting confidence for the general public,” Prayuth told reporters at Government House, before he received a shot in his left arm. Prayuth, who will turn 67 this month, later said he felt fine after the injection. Thailand’s health minister said on Monday the rollout would resume after many countries had said there were no blood clot issues with the vaccine.19

Thailand has started vaccinating frontline health workers and other groups including government officials using imported shots but the country’s overall vaccination strategy is heavily reliant on making the AstraZeneca vaccine domestically.20

The AstraZeneca vaccine is due to be produced by a company owned by the country’s king, with 61 million doses reserved for the country’s population. The Thai-produced AstraZeneca vaccine is not expected to be available until at least June, when Thailand plans to begin its mass inoculation campaign. Prayuth and his cabinet were injected with some of the 117,300 doses of imported AstraZeneca vaccine Thailand received for emergency use earlier this month.21

Thailand previously imported 200,000 doses of Sinovac’s CoronaVac. A further 800,000 CoronaVac doses would arrive later this month, followed by a million more in April.22

All these did not prevent Thailand from also suspending or pausing the use of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine alongside other European countries. The EU geopolitic has ostensibly catch up with Thailand from which it could not escape its entrapment.

The rejection of the vaccine is continental-wide, from Benelux, Nordic to Central European countries. The “Big Boys”: Germany, France, Italy, Spain including Austria joined the “riotous” crowd of “smaller countries” to reject the vaccine. Nothing like this has ever happened in recent memory. Something is unarguably fundamentally wrong somewhere. Britain did not ostensibly bargain for this poor reception and rejection of a notable pharmaceutical drug, a virus vaccine in this case, at this point in time. It came out of the dark cloud, unplanned for!

How the Oxford/AstraZeneca controversy blew open

The rejection of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine came like a thief in the night. Apparently in the day, the University and the pharmaceutical giant have committed blunder that would brought the thief into the household in the night. There is no effect without a cause or vice versa. The duo can be seen to have been negligent of certain details and procedures that would collectively come to cost them their reputation and enotmous financial loss. The event that started as honey would turn out to be vinegar.

The problem started with was initially perceived to be that of demand-and-supply disequilibria.

After months of research and a week-long controversy over a reduction in expected vaccine supply, regulators in Europe have authorized AstraZeneca’s two-dose COVID-19 vaccine.23 The vaccine, the result of AZ’s collaboration with Oxford University, is conditionally approved across Europe in people ages 18 and older. A broad rollout in EU member countries will follow, but in recent days, a reduction in first-quarter supply has dominated headlines.24

Last week [i.e. early February 2021], AstraZeneca notified EU officials of manufacturing problems in its supply chain that would cause it to drastically cut first-quarter shipments to the continent. An intense back-and-forth [negotiation] followed, and on Friday, Europe restricted exports of COVID-19 vaccines.25

On a call with reporters Friday, AstraZeneca CEO Pascal Soriot said that manufacturing processes typically take years to develop and refine. During the pandemic, the company and its production partners have set up the manufacturing process in the span of “a few months.” The result is that millions of doses will be available sooner, he said, but still the process hasn’t been fully refined at all of the sites. Some sites are farther along in the “learning curve,” he said, so AZ is seeing a “variability of yield” throughout different sites in its network. The company has had a “good discussion” with Europe and is focused on improving supply, he said.26

The AstraZeneca authorization follows similar green lights from European officials for mRNA vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna. But while those vaccine regimens require doses to be given several weeks apart, AZ’s shots can be administered between 4 and 12 weeks part, providing for greater flexibility, Soriot noted. That means if AZ ships an initial 20 million doses, European health officials could use all of them to start to vaccinate 20 million people, he said. Then, up to three months later, those recipients could get their second shots from another shipment.27

It would soon turn out that the demand-and-supply disequilibra is not the only problem plaguing the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine. More potent is the two-dose connundrum that has been lurking in the backing until it blew open to the public domain. This was to become more problematic than imagined by the forces behind the vaccine production and roll-out. It all started with several countries expressing doubts about the efficacy of the vaccine in people over 65 years of age when tests revealed two different sets of result for people of two different age group.

In its phase 3 trial, AstraZeneca’s vaccine was 70% effective overall, but a dosing error yielded a higher result in a subset of participants. For people who received a half dose followed by a full dose, vaccine efficacy was 90%. The trial results prompted AZ to run another study for a potential emergency use authorization in the U.S. That study is fully enrolled and set to read out next month [February 2021], AZ execs said on Friday’s call.28

AZ’s authorization came right after COVID-19 vaccines from Novavax and Johnson&Jonson posted their own phase 3 data. Soriot called all of the developments “positive news for the entire world.”29

Pascal Soriot could now be seen to be gravely mistaken in his euphoria. While the world might have been celebrating the arrival of various vaccines into the global market shelf and the subsequent rolling out of the vaccination exercise, the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine of which he is the main supervisor hit a brickwall across the English Channel in the continental Europe. Ostensibly, Soriot did not, in his wildest imagination, bargain for the nasty reception of the vaccine across the English Channel. He did not see it coming at all. Even when the error in dosing was discovered, he still could not expect that European Union would develop cold feets and outrightly ban the vaccine from being administered to citizens across Europe.

The dosing error would become a Frankenstein monster in the boardroom of AstraZeneca and University of Oxford threatening to scatter and undo all the previous investment in the vaccine. It became the strategic faux-pax for which the EU is now threatening to hang or guillotine the vaccine by the roadside for all to see the ugly spectacle of a public execution.

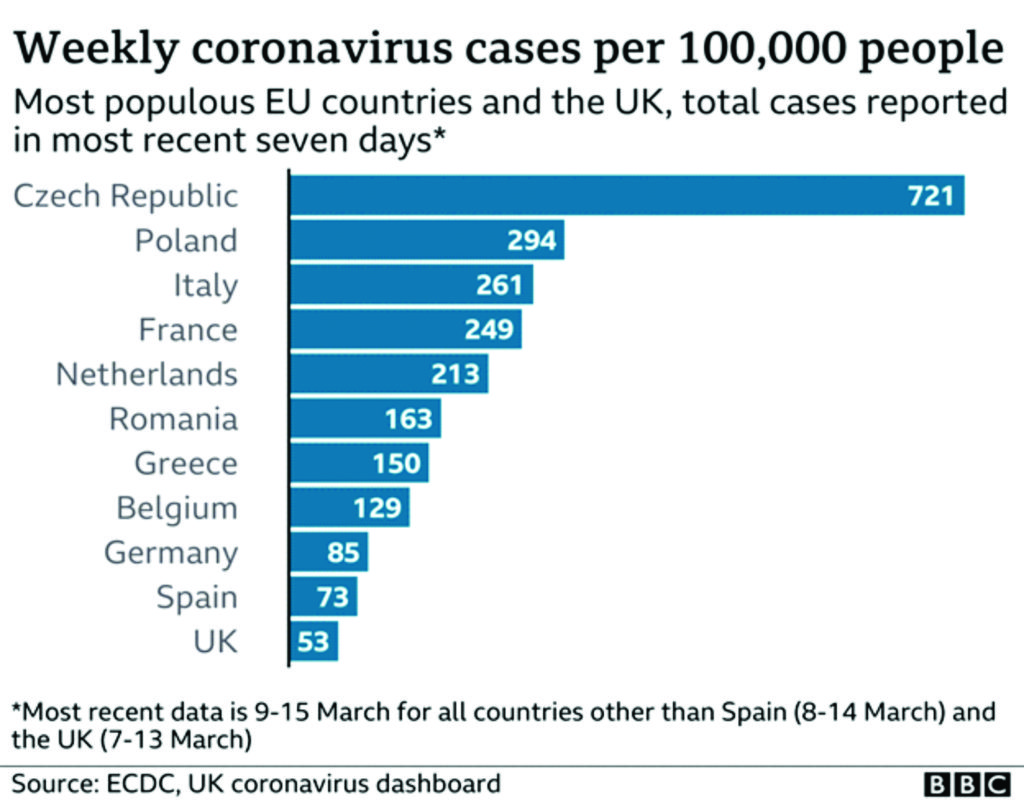

There is no doubt that these were some of the same countries that performed poorly, that were practically seen to be helpless when the pandemic was raging and ravaging their countries, plucking off their citizens in thousands and sending them to the Greater Beyond. But when suddenly some couple of people died with or without causal connection to the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine they suddenly became holier-than-thou, seemingly hitting vengefully back at Britain where it is most painful, giving it a bloody face with a heavy punch to the nose. It is analogous to a street brawl where a lone individual was given a beating of his life by a gang of bad boys.

How University of Oxford found itself in this ugly and messy situation may probably never be understood. But there can be no denial of the Oxford’s good intention about its foray into the scientific and medical search for the vaccine solution to the raging pandemic. Its venture is salutory. Its collaboration with AstraZeneca may not also be questioned on the basis of this good volitional intention to find vaccine for the coronavirus pandemic. In short, University of Oxford stands on unquestionable high philosophical, scientific, medical and even political pedestals as regard its involvement and engagement with AstraZeneca to produce the AZD1222 vaccine for the British and world markets.

However, Oxford/AstraZeneca found itself in a hyper-competitive environment among the world top-most Big Pharma vaccine makers including those sponsored directly by Governments, for instance, in Russia and China. It is a clustered global environment only meant for the “Big Boys” in the pharmaceutical industry. Every company engaged and working to produce the first vaccine for the coronavirus pandemic find itself working under extreme pressure in a VUCAed environment of vulnerability, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity that have also come to affect and pervade the global scientific community to a large degree like the geopolitical environment. It is a rat- or horse-race to the top of the ladder!

Its sins may probably be found in the manner it approached the enterprise: the procedures adopted, the pressure mode under which its scientists forced themselves to work in the race for the vaccine knowing fully the dangers involved in such conditions. Under such pressurized and/or heated environment, mistake can easily occur. Under this perceptible unbearable conditions, a slip or slight mistake becomes costly in its composite effects. And that was exactly what happened.

Thus, in passing the final judgment, University of Oxford may not be accused of wilful intent to cause harm to any of the end-users of the AZD1222 vaccine – for instance, all those who are claimed to have died as a result of blood clot linked to the vaccine. By extension too, AstraZeneca may not also be accused of such “evil” intention at all. What happened was a combination of avoidable “errors” that conspired against the perceptible good volition to serve and save humanity from the skulduggery and yoke of the coronavirus pandemic.

However, the error, mistake, snafu (several adjectives have been deployed to describe what has happened – depending on the sentiment of the individual writer) that has come to lead to international controversy dates back to 2020. The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine problem started late 2020 precisely when it was announced as a “breaking news” which sent the British populace into wild jubilation that would later turn awry and sour in the mouth by March 2021. A back-review reveals that something momentous has gone wrong in the process of producing and testing the efficacy of the vaccine.

A good account of what transpired during the experimental stage of the vaccine was provided by Fergus Walsh reporting for BBC News.30 It is a story of intrepid scientists (such as Prof Teresa Lambe, Prof Sarah Gilbert, and Prof Andrew Pollard) working round the clock to find the template for the new experimental coronavirus vaccine. Interestingly, this was in January 2020 when the coronavirus from China has not even been declared a pandemic by any official quarter. These scientists may have been guided by intuition, whether they are aware of this or not, to embark on this journey that brought the whole British society to where it is today. The scientists were looking for the Weapon X to fight what was coming on the horizon not knowing exactly what this enemy look like. The Weapon X is what turned out to be the Oxford/AstraZeneca (AZD1222) vaccine they had agreed upon to be the stealth or visible fighter against the coronavirus.

In the early hours of Saturday 11 January, according to Fergus Walsh in his report, Prof Teresa Lambe was woken up by the ping of her email. The information she had been waiting for had just arrived in her inbox: the genetic code for a new coronavirus, shared worldwide by scientists in China. She got to work straight away, still in her pyjamas, and was glued to her laptop for the next 48 hours. “My family didn’t see me very much that weekend, but I think that set the tone for the rest of the year,” she says. By Monday morning, she had it: the template for a new experimental coronavirus vaccine. The first death from the new virus was reported around the same time, but it was still a month before the disease it causes was named Covid-19.31

Lambe’s team at Oxford University’s Jenner Institute, led by Prof Sarah Gilbert, was always on the lookout for Disease X – the name given to the unknown infectious agent that could trigger the next pandemic. They had already used their experimental vaccine system against malaria and flu and, crucially, against another type of coronavirus, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (Mers). So they were confident it could work again.32

That weekend was the first step on a journey to create a vaccine at lightning speed, for a disease that would, in a matter of months, claim more than 1.5 million lives. … There have been dramas along the way, including:

- a rush to charter a jet when a flight-ban prevented vaccine from getting into the country

- dismay at totally false reports on social media that the first volunteer to be immunised had died

- concern that falling infection rates over the summer would jeopardise the hope of quick results

- how an initial half-dose of the vaccine unexpectedly provided the best protection

- an admission from the chief of Oxford’s partner, drug company AstraZeneca, that it would have run the trials “a bit differently”.

In the middle of January Prof Andrew Pollard, the director of the Oxford Vaccine Group, which runs clinical trials, shared a taxi with a modeller who worked for the UK government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies. During the journey, the scientist told him data suggested there was going to be a pandemic not unlike the 1918 flu. “I went from someone who was aware of a small outbreak in China, which was of academic interest, to realising that it was going to change our lives. It was a chilling moment,” Pollard says.33

Trouble, however, seemed to start during the trial, i.e. testing the efficacy of the vaccine which was found to be satisfactory, without side-effects, up to a point. The green light to go ahead wth the mass production of the vaccine was already flashing on the dashboard.

As the trial grew, it was clear that Oxford’s small manufacturing facility would not be able to keep up with demand. The team decided to outsource some of the manufacturing to Italy. But when the first batch was ready, there was a snag – the Europe-wide lockdown meant there were no flights to airlift it from Rome. “Eventually we chartered a plane to bring 500 doses of vaccine because it was the only way we could get it here in time,” says Green.34

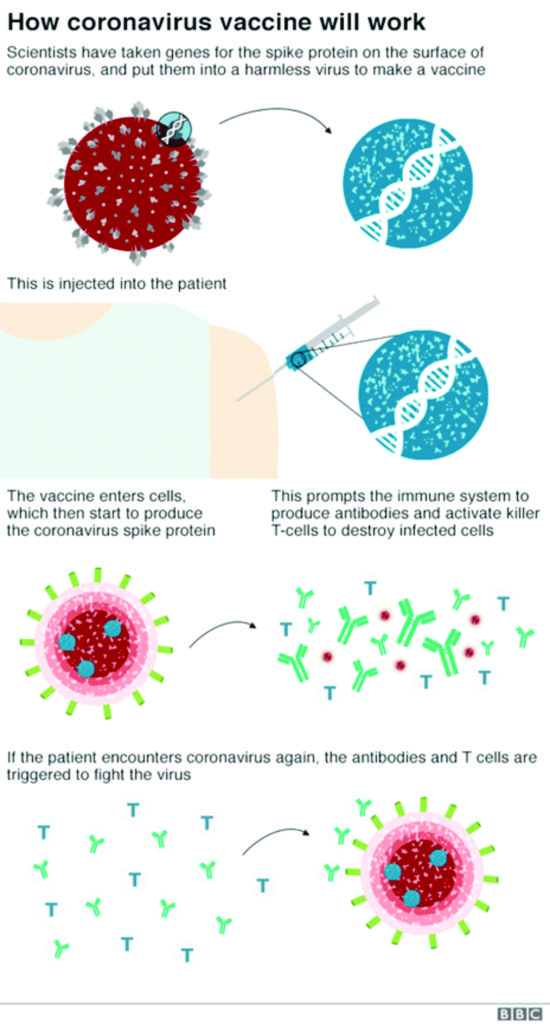

This is a really important part of the story which ended up being highly significant months later.35

The Italian manufacturers used a different technique to Oxford to check the concentration of the vaccine – effectively how many viral particles are floating in each dose. When the Oxford scientists used their method, it appeared that the Italian vaccine was double strength. What to do? Calls were made to the medical regulators. It was agreed that volunteers should be given a half measure of the vaccine, on the basis that it was likely to equate to something more like a regular dose. This was partly a safety issue – they preferred to give them too little rather than too much.36

But after a week, the scientists became aware that something unusual was going on. The volunteers were getting none of the usual side-effects – such as sore arms or fever. About 1,300 volunteers had only received a half-dose of the vaccine, rather than a full one. The independent regulators said the trial should continue and that the half-dose group could remain in the study.37

The Oxford team bristle at any suggestion that there was a mistake, error, call it what you will. Perhaps the most accurate characterisation is that the volunteers were inadvertently given a lower dose. In months to come, they would be the stellar group in terms of vaccine efficacy.38

From the start, the team at Oxford had had the goal of creating a vaccine that could help the world. To do that they would need billions of doses – something only industry could provide. Sir Mene Pangalos, of the Cambridge-based pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca, suggested the company could help.39

But there was a potential hitch – Oxford insisted the vaccine should be affordable, which meant no profit for the pharmaceutical company. “Not usually the way big pharma works,” says Pollard.40

After intense negotiations, they reached a deal at the end of April. The vaccine would be provided on a not-for-profit basis worldwide, for the duration of the pandemic, and always at cost to low- and middle-income countries. Most importantly of all, AstraZeneca agreed to take on the financial risk, even if the vaccine turned out not to work. In May, in a huge vote of confidence, the UK government agreed to buy 100 million doses and provided nearly £90m in support. By then there were nearly a dozen coronavirus vaccines in human trials around the world.41

On 20 July, the initial results were released, showing whether the vaccine had stimulated the immune systems of the first 1,000 volunteers. The team was feeling the pressure. “I’ve worked in vaccines for long enough to know that most vaccines actually don’t work. And it’s the worst feeling in the world to have such high expectations and then to see nothing,” says Prof Katie Ewer, who leads the team studying T-cell response.42

It was good news, though. The vaccine appeared to be safe, and had triggered the two-pronged immune response they were hoping for – producing antibodies which neutralise the virus, and T cells which can kill cells which have become infected. But the data also led to a change of strategy. Until then, the Oxford team had hoped to produce a vaccine that could be delivered in a single dose, so there was more vaccine to go round.43

However, 10 participants who were given two doses showed a much stronger immune response, so all volunteers were invited back for a booster, to maximise the chances of protection. Although these early results were promising, at this stage there was still no evidence to show whether the vaccine would actually protect against Covid-19.44

Intriguingly, when the trial results came out, there were indications it may partly suppress transmission of the virus. But more evidence is needed. By the end of the summer, trials of the vaccine were running in six countries including the UK, Brazil, South Africa and the United States. Nearly 20,000 volunteers had been recruited. But on 6 September suddenly everything stopped. A participant had developed a rare neurological condition. “In a clinical trial of tens of thousands of people, stuff happens,” says Pollard. “People develop illnesses, there will be people who develop cancers and who develop neurological conditions – the difficulty… is to work out whether it’s associated with the… vaccine.45

An independent safety review did not find any reason to suspect the illness had been caused by the vaccine. But they couldn’t rule it out either. The volunteer is still part of the trial and is recovering. Safety regulators in the UK, Brazil and South Africa gave the green light for the trials to resume within days, but it was six weeks before they were allowed to resume in the US. All this came amidst a climate of anti-vaccine sentiment – not just online, but with demonstrations taking place around the world.46

Transparency and openness about the vaccination process is one way of overcoming such mistrust. This is partly why the extremely busy team of scientists has given the BBC access to their labs over the past year.47

Finally, on 21 November, the independent data safety committee was ready to reveal the Oxford-AstraZeneca findings. But the results were surprising – and more complex than expected. Whereas Pfizer and Moderna had one efficacy figure from one big trial each, the Oxford jab ended up with three numbers: 70% overall, with the two full doses giving 62% protection while the smaller group, who were given that initial half dose had the highest protection, had 90%. It was a result no one had expected.48

Crucially, no one who got the vaccine was hospitalised or got seriously ill due to Covid. Whereas in the control group there were 10 serious cases and one death. The fact that those who had unwittingly been given the initial half dose from Italy showed stronger protection is intriguing. It may be caused by the immune system being primed more gradually, but the scientists can’t yet explain it. Also, all the volunteers in this group were under 55.49

Real trouble started with this death that was argued to be as a result of blood clotting linked to the vaccine. Oxford/AstraZeneca refused to accept this possible linkage. According to Ewen Callaway, the analysis of the result produced both interesting and head-scratching effects. “A highly anticipated COVID-19 vaccine has delivered some encouraging — but head-scratching — results. The vaccine developed by the University of Oxford, UK, and pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca was found to be, on average, 70% effective in a preliminary analysis of phase III trial data, the developers announced in a press release on 23 November [2020].”50 But the analysis found a striking difference in efficacy depending on the amount of vaccine delivered to a participant. A regimen consisting of 2 full doses given a month apart seemed to be just 62% effective. But, surprisingly, participants who received a lower amount of the vaccine in the first dose and then the full amount in the second dose were 90% less likely to develop COVID-19 than were participants in the placebo arm.51

It was this discepancy in the result produced that was at the heart of the controversy. The argument is whether those who died from blood clot was as a result of (first) lower dosage or the second dosage or vice versa.

The Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine is made from a cold-causing adenovirus that was isolated from the stool of chimpanzees and modified so that it no longer replicates in cells. When injected, the vaccine instructs human cells to produce the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein — the immune system’s main target in coronaviruses. The vaccine entered phase III efficacy trials before other front runners, including Pfizer and Moderna, and trials are continuing in countries including the United States, South Africa, Japan and Russia. The 23 November analysis is based on 131 COVID-19 cases among more than 11,000 trial participants in the United Kingdom and Brazil, up to 4 November.52

Overall, the developers found that the 2-dose vaccine had an efficacy of 70%, when measured 2 weeks after participants received their second dose. But that figure is an average of the 62% and 90% efficacy from the two dosing regimens. “90% is pretty good, but the 62% for the second tested regimen are not that impressive,” said Florian Krammer, a virologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, on Twitter.53

A top priority for researchers is understanding why the vaccine seems to have performed so much better with a lower first dose. One explanation could lie in the data: the trial might not have been big enough to gauge the differences between the two regimens, in which case the differences might vanish once more cases of COVID-19 are detected, says Luk Vandenberghe, a virologist at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear institute and Harvard Medical School in Boston. The more effective ‘half-dose, full dose’ results were based on 2,741 trial participants, whereas the less efficacious arm included 8,895 volunteers. The press release did not specify in which group cases occurred.54

But, if the differences are real, researchers are eager to understand why. “I don’t think it’s an anomaly,” says Katie Ewer, an immunologist at Oxford’s Jenner Institute who is working on the vaccine. “I’m keen to get into the lab and start thinking about how we address that question.” She has two leading theories for why a lower first dose might have led to better protection against COVID-19. It’s possible that lower doses of vaccine do a better job at stimulating the subset of immune cells called T cells that support the production of antibodies, she says.55

Another potential explanation is the immune system’s response to the chimpanzee virus. The vaccine triggers a reaction not only to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, but also to components of the viral vector. It’s possible that the full first dose blunted this reaction, says Ewer. She plans to look at antibody responses to the chimpanzee virus to help address this question.56

“This is a plausible explanation,” says James Wilson, a virologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia who pioneered the use of adenoviruses for vaccines in the 1990s. By giving a half-dose first, “it is possible that AstraZeneca threaded the needle with their dosing”, he adds.57

AstraZeneca has said a review of safety data of 17 million people vaccinated with its Covid-19 vaccine has shown no evidence of an increased risk of blood clots. “A careful review of all available safety data of more than 17 million people vaccinated in the European Union and UK with Covid-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca has shown no evidence of an increased risk of pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis or thrombocytopenia, in any defined age group, gender, batch or in any particular country,” the company said. The drugmaker said there have been only 37 reports of blood clots among the more than 17 million people who have received the vaccine across the EU and Britain, which may have been just a coincidence.58

The big question is whether there is coincidence in science, something which philosophy of science has not been able to answer till date.

In a University of Oxford website the argument was made that “It is recognised that a vaccine is urgently needed to prevent people from becoming severely ill and dying from COVID-19. The aim of the UK COVID-19 vaccination programme is to protect those who are most at risk. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists around the world have come together to focus their efforts on developing vaccines to prevent people from becoming infected with the coronavirus. Over 270 vaccines are in various stages of development, and some of these utilise similar technologies to existing vaccines in use, whilst others involve newer approaches.59

Although clinical trials have been completed more rapidly during the pandemic, this has been achieved by overlapping the different stages (phase 1, 2 and 3) of clinical testing rather than completing them sequentially. Assessment of safety has not been compromised and the trials have been subject to the same strict regulatory requirements as any other vaccine studies. Each of the vaccines that has received or is under review for temporary licensing have been tested in trials with over 20,000 people, collecting many months of safety follow-up data. In many cases, these trials are larger than trials for other drugs and vaccines which have been licensed.”60

In the UK, two vaccines are currently in use, following regulatory approval. These are the BNT162b2 vaccine, developed by Pfizer and BioNTech and the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222), developed by the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca. Both of these vaccines have been authorised for emergency use by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), as well as a vaccine developed by Moderna, which is expected to be available from Spring 2021.61

The ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine was developed by the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca. The vaccine works by delivering the genetic code of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the body’s cells, similarly to the BNT162b2 vaccine. Once inside the body, the spike protein is produced, causing the immune system to recognise it and initiate an immune response. This means that if the body later encounters the spike protein of the coronavirus, the immune system will recognise it and destroy it before causing infection.62

This Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine uses the ChAdOx1 technology, which has been developed and optimised by the Jenner Institute over the last 10 years. This type of vaccine technology has been tested for many other diseases such as influenza (flu) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), another type of coronavirus.63

The ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine has been tested by the University of Oxford in clinical trials of over 23,000 people in the UK, Brazil and South Africa. AstraZeneca are also running a further trial with 40,000 people in the USA, Argentina, Chile, Columbia and Peru.64

Interim results from the UK and Brazil trials showed that the vaccine can prevent 70.4% of COVID-19 cases. This was calculated across two different groups of people, who received two different dose regimens. The vaccine was shown to prevent 73% of cases in individuals with at least one underlying health condition. The vaccine has also been shown to produce similar immune responses in older adults when compared with young, healthy individuals, although the efficacy data for this group is not yet available. The ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine is given as a two-dose course, which is given as an injection into the upper arm. The second dose is given 4-12 weeks after the first dose.65

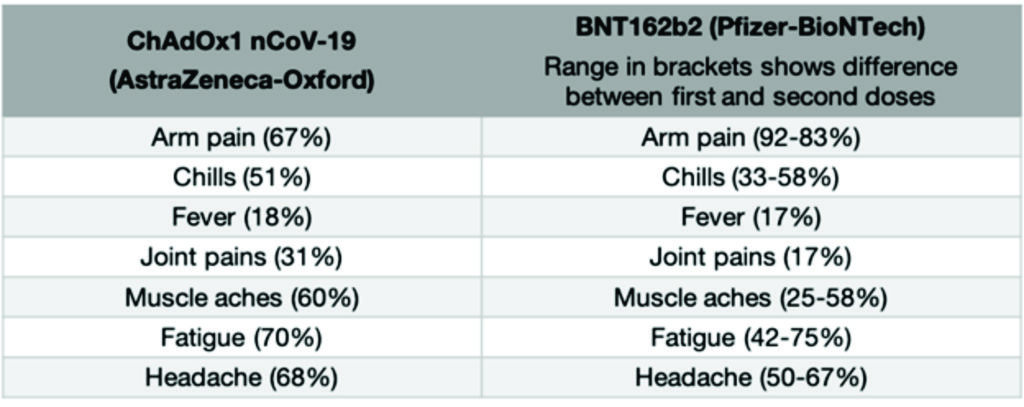

Because vaccines work by triggering your immune system to produce a reaction, you can however have side effects after you receive the vaccine that feel similar to having a real infection. Things like having a fever, or feeling achey, or getting a headache (often described as “flu-like” symptoms) are common after receiving many vaccines and this is the same for the approved COVID-19 vaccines. Having these symptoms means that your immune system is working as it should be. Usually, these symptoms last a much shorter time than a real infection would (most are gone within the first 1-2 days). The common side effects associated with the currently approved vaccines are below. These symptoms generally last 1-2 days following vaccination.

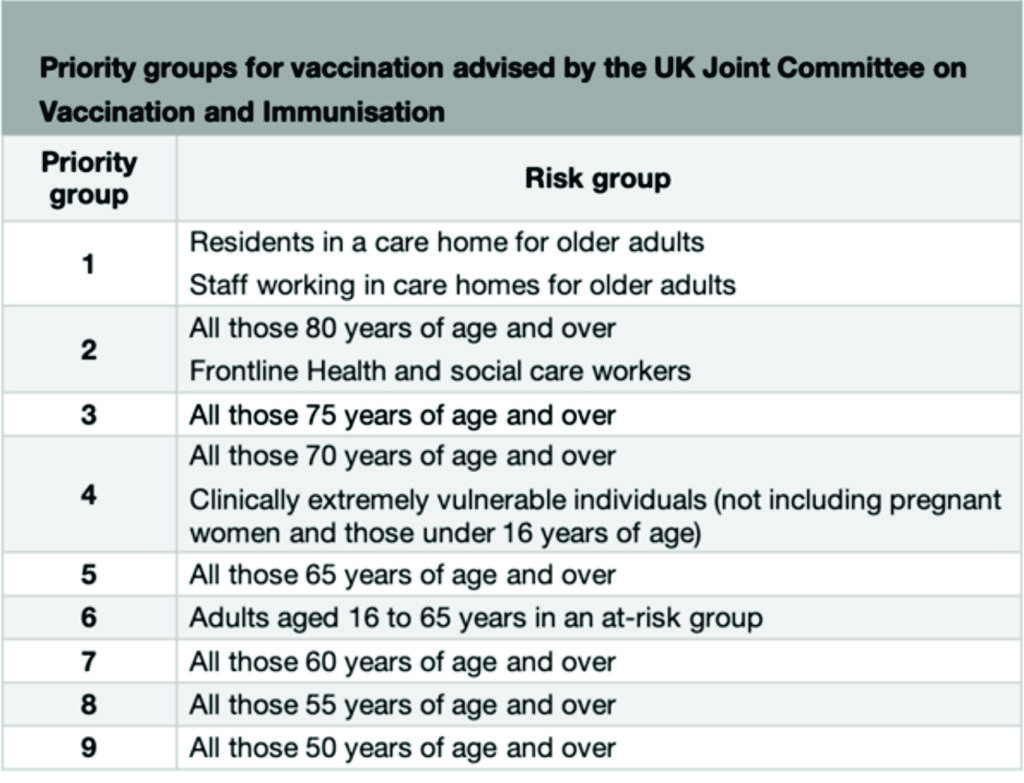

Following advice from the UK Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation, the programme will vaccinate people in the order of highest risk of severe COVID-19 disease, due to occupation, age or other risk factors. The categories are outlined below:

At-risk groups included in priority group 6 are:

- Chronic respiratory disease (including severe asthma)

- Chronic heart disease and vascular disease

- Chronic kidney disease

- Chronic liver disease

- Chronic neurological disease

- Diabetes

- Immunosuppression

- Dysfunction of the spleen

- Morbid obesity

- Severe mental illness

- Adult carers

- Younger adults in long-stay care homes

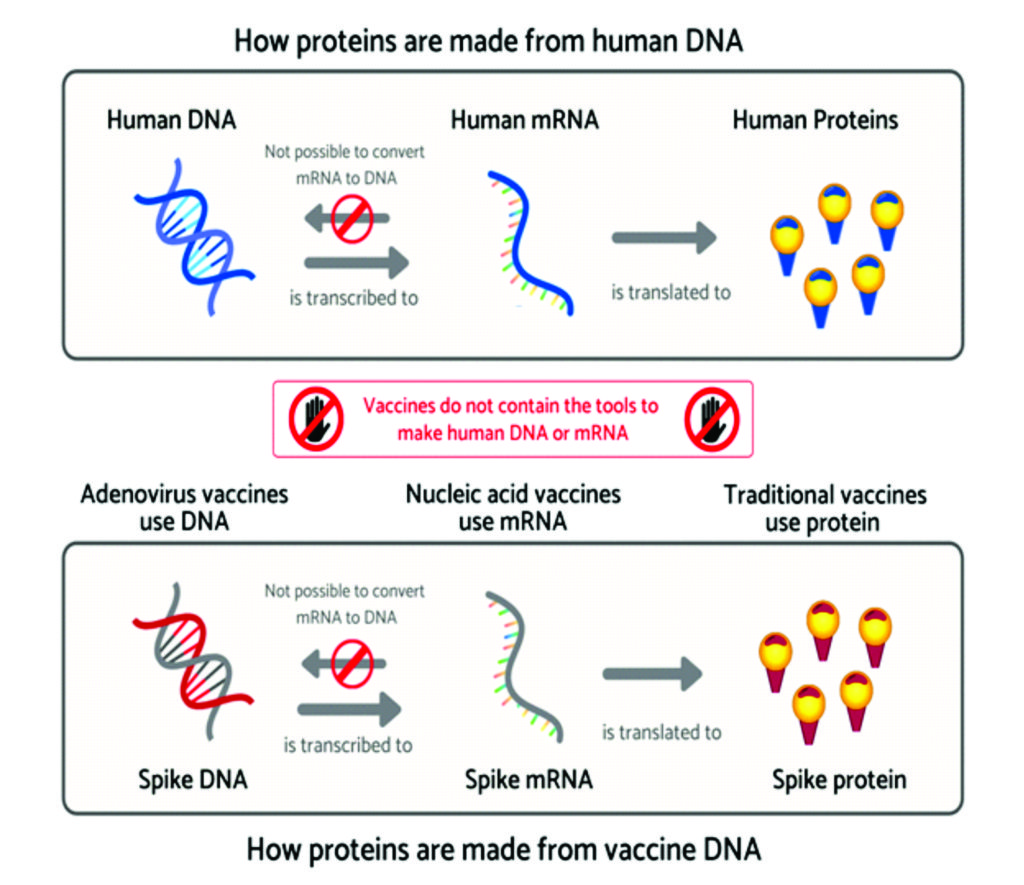

Newer vaccines such as mRNA vaccines and viral vectored vaccines, including the Oxford ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine differ from many traditional vaccines in the way they activate the immune system. Most traditional vaccines inject the antigen (part of the disease that stimulates an immune response) directly into the body. In contrast, these two newer approaches deliver the genetic instructions for the antigen to the body’s cells. The cells then manufacture the antigen which goes on to stimulate the immune response. Injecting genetic material has raised questions about the use of these vaccines, such as whether they can modify the DNA of those receiving them. Here, we will explain why this is not possible.66

A Reuters group of reporters also provided a special report that offers insights into what might have happened within the University of Oxford team of scientists working on the controversial vaccine.

The reporters reported that “On June 5 [2020], researchers at the University of Oxford quietly made a change to a late-stage clinical trial of their COVID-19 vaccine. In an amendment noted in a document marked CONFIDENTIAL, they said they were adding a new group of participants.67

The adjustment might seem minor in a large-scale study. But it masked a mistake that would have potentially far-reaching consequences: Many of the United Kingdom trial subjects had inadvertently been given only about a half dose of the vaccine.68 The new volunteers would now receive the correct dose. The trial continued.69

Much was riding on the Oxford vaccine, a British-led endeavour also involving UK drugs firm AstraZeneca. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government was desperate for a success story after its early mishandling of the pandemic contributed to one of the world’s highest death tolls from COVID-19 – around 65,000 by mid-December. The government has secured 100 million doses.70

On Nov[ember]. 23, [2020] Oxford and AstraZeneca delivered positive news. They announced that the regimen of a half dose followed by a full dose booster appeared to be 90% effective in preventing COVID-19. Two full doses scored 62%. Oxford researchers have said they aren’t certain why the half-dose regimen was much more effective.71

Some experts say the dosing discrepancy raises doubts about the robustness of the study’s findings. And they worry about another acknowledged peculiarity of the study: The half-dose regimen wasn’t tested on anyone over 55 – the group considered at high risk from COVID-19. In contrast, a vaccine produced by Pfizer/BioNTech was tested on thousands of people over 65, with an efficacy of 94%.72

John Moore, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, said there needed to be a better understanding of how the Oxford trial unfolded. “When you get corporate and academic scientists saying different things, it doesn’t give you the impression of confidence in what they’re doing,” he told Reuters. “Was the dosing thing a mistake or not?”73

Now a Reuters review of hundreds of pages of clinical trial records, as well as interviews with scientists and industry figures, provides the most detailed account to date of what went wrong with the dosing in the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine study. The review found that Oxford researchers were responsible for what their own clinical trial documents called “a potency miscalculation.”74

For Oxford and AstraZeneca, the stakes could not be higher. They hope to produce up to three billion doses of the low-cost vaccine by the end of next year, enough to inoculate much of the world, including many of its poorest inhabitants. For months, scientists at Oxford have been busily promoting the experimental vaccine’s prospects in bullish terms – beginning even before the first human test subjects were injected with the experimental vaccine.75

In an interview that appeared on April 11 in Britain’s The Times newspaper, Sarah Gilbert, one of the vaccine’s chief researchers at Oxford, said she was 80% certain her team would be able to produce a successful vaccine, possibly as early as September. That was 12 days before a clinical trial to test its safety began.76

Oxford didn’t answer detailed questions for this story, but provided a statement saying the trials have been “conducted under the strict national, ethical and regulatory requirements.” It added that “all trial protocols and trial amendments have been subject to review and approval by the relevant authorities. All safety data have been reviewed regularly” by regulators.77

A spokesman for AstraZeneca referred questions about the UK clinical trial to Oxford, which sponsored it. A spokeswoman for Britain’s regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), declined to answer questions about the Oxford/AstraZeneca dosing issue. “Our rolling review is ongoing,” she said, “so this information is currently commercially confidential.”78 The UK’s Department of Health and Social Care declined to comment.79

On Dec. 8, Oxford published an interim analysis of its trial results and more than 1,100 pages of supplementary documents in the scientific journal The Lancet. These show that measuring the concentration of viral materials can be tricky, and they shed light on the chain of events leading up to the dosing discrepancy.80

According to the Oxford documents, in May researchers received a vaccine delivery from Italy’s IRBM/Advent — one of the contract manufacturers Oxford enlisted to complement its own vaccine production. The late-stage trial of the Oxford vaccine was about to begin.81

The shipment, batch K.0011, had undergone the Italian company’s quality check using an established genetic test – quantitative PCR, or qPCR – to determine viral matter per milliliter.82

Oxford ran its own analysis for good measure. The university had been using a different method known as spectrophotometry, which measures viral material in liquids based on how much ultraviolet light the viral matter absorbs.83

Oxford’s measurement showed that the batch was more potent than the Italian manufacturer had found, the documents show. Oxford trusted its own result and wanted to remain consistent with a measuring tool it had used throughout an earlier trial phase. So it asked Britain’s drugs regulator for permission to reduce the volume of vaccine injected into trial participants from the K.0011 batch. Permission was granted.84

“The decisions about dosing were all done in discussion with the regulator. So when we started the trial, we had some discrepancies in the measurement of the concentration of virus in the vaccine,” Andrew Pollard, the Oxford trial’s chief investigator, told Reuters.85

A spokeswoman for the regulator declined to discuss when it first became aware of the dosing issue.86

Trial participants who received shots from the Italian batch displayed milder than normal expected side effects, such as fever and fatigue. AstraZeneca executive vice president Mene Pangalos said the dose was measured incorrectly. “It ended up being half the dose,” he told Reuters. He called the mistake “serendipity,” given that data analysis later indicated the half dose, followed by a full-dose booster shot, was much more effective than two full doses.87 He also recently told the BBC: “There is no doubt I think that we would have run the study a little bit differently if we had been doing it from scratch. But ultimately, it is what it is.”88

IRBM/Advent told Reuters there was no manufacturing issue with the batch. The company said in a written statement that the measuring mishap was “the result of a change in the testing method” used to confirm the potency of the dose “once the material had been shipped.”89

The documents published in The Lancet confirm that the error lay with the Oxford researchers. A common emulsifier, polysorbate 80, used in vaccines to facilitate mixing, had interfered with the ultraviolet-light meter that measures the quantity of viral material, according to the documents. As a result, the vaccine’s viral concentration was overstated and Oxford ended up administering half doses of vaccine, believing they were full doses.90

The documents don’t give a detailed timeline, nor do they show that Oxford informed AstraZeneca at the time. But they do show that Oxford contacted the British regulator again, this time seeking approval to change its measuring method to the one used by the Italians, and to figure out how to proceed with a late-stage trial that had begun with participants receiving the wrong dose. The documents don’t provide full details of the communication between Oxford and the regulator.91

However, there was a startling revelation in the report by the Reuters reporters

Deep within the more than 1,100 pages of supplemental appendices published in The Lancet appeared a description of the dosing discrepancy — “a potency miscalculation.” That admission is contained in a “Statistical Analysis Plan” by Oxford and AstraZeneca dated Nov. 17.92 Six days later, Oxford and AstraZeneca announced the interim results of their clinical trials in the UK and in Brazil. “Oxford University breakthrough on global COVID-19 vaccine,” was the headline of an Oxford press release.93

AstraZeneca’s news release was more muted. “Two different dosing regimens demonstrated efficacy with one showing a better profile,” it stated. (Ibid) In interviews about the results with Reuters and the New York Times, AstraZeneca’s Pangalos spoke of “serendipity,” a “useful mistake” and a “dosing error.”94 But the firm’s chief executive officer, Pascal Soriot, told Bloomberg: “People call it a mistake — it was not a mistake.” A spokesman for AstraZeneca declined to comment on the statements.95

Meanwhile, the two scientists leading Oxford’s development of the vaccine — Sarah Gilbert and Adrian Hill — suggested that the half-dose was not administered by mistake. They didn’t provide evidence. Gilbert, an Oxford vaccinology professor, said it was normal for researchers to look at different dose levels during vaccine trials. “It wasn’t a mix-up in dosing,” she told the Financial Times in an article published on Nov. 27.96 A few days later, Hill told Reuters it was a conscious decision by researchers to administer a lower dose. “There had been some confusion suggesting that we didn’t know we were giving a half dose when we gave it — that is really not true,” he said.97

Gilbert and Hill together have about a 10% stake in a private biotech firm called Vaccitech that was spun out of Oxford University, according to a filing with Companies House, the UK’s companies’ registry, dated Oct. 29. According to a spokeswoman for Vaccitech, the company transferred its rights to the vaccine to Oxford University’s research commercialization arm in exchange for a share of the revenue. “If the vaccine is successful then all shareholders and investors in the company could potentially indirectly benefit,” she wrote in an email.98 Hill and Gilbert didn’t respond to detailed questions for this article.99

Some big questions are these: Could there have been a cover-up about the dosing discrepancy among the scientists? Or was just a pure mistake or error? Why are the Oxford scientists unwilling to even entertain the idea of a mistake or error in their work? Why not go all over again in reviewing their works to see whether there may have been a point (currently overlooked) where this mistake or error could have happened? Was this unwillingness to review their works all over again not against openess and transparency which the group has hitherto demonstrated? Are there plausible deniability for such mistakes or errors? Were there conflicts of interests as reported in the Reuters’ special report above? Are these conflicts of interests jurisprudentially criminal in nature? Can they be prosecuted?

What has become apparent from the above analysis is that there is no hiding place once a slip, mistake or error has been made either deliberately or inadvertently. The only option is to come out clean and openly rather than hide behind stubborness or obstinacy that further escalates the crisis. It is obvious that the Oxford team of scientists were trying to hide their mistake or error from public scrutiny. Several officials contacted by the Reuters’ reporters declined to comment or answer questions put to them which can be interpreted to mean they are aware of something having gone wrong but playing safe. They were probably clumsy at doing this given the inquisitiveness through the media: print and social media some of which rely on sensational reporting to attract wider followership. This is another whole dimension to the controversy: how media fed into the crisis and escalated it to the stratosphere. It might not be out of place to suggest that the EU countries that have rejected the vaccine acted while hiding behind the preponderant weight of public opinion aggregated through the media in order to quickly divert public opinion from their hitherto poor performance in handling the coronavirus pandemic when is was at its raging peak.

The Political Tango between Britain and EU

The political angle to the controversy was thrown open by none other than an article that appeared in prestigious and respected The Lancet medical journal in February 2021 by Rob Hyde.

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen made a startling speech last week in relation to widespread criticism of how Europe has so far handled the COVID1-19 vaccine roll-out. “We were late in granting authorisation. We were too optimistic about mass production. And maybe we also took for granted that the doses ordered would actually arrive on time”, she said. Views differ widely, however, on whether the EU did anything wrong in how it went about securing vaccines for its citizens.100

The EU aims to both secure vaccine supplies, and also provide support for the development of further vaccines in the union. Its approach is centralised. The Commission acts on behalf of all 27 member states by negotiating advance purchase agreements with vaccine manufacturers. Approval is then made by the European Medical Agency (EMA).101

The benefit of this approach is that, in theory, the EU can secure lower prices. As a huge bloc, the EU should have significant bargaining power in negotiations. Another advantage is that vaccines are ordered on behalf of all EU countries. This stops wealthier states such as Germany, France, and the Netherlands buying up all available vaccines, leaving nothing for economically weaker states such as Romania and Bulgaria.102

According to the EU’s website, its vaccine strategy is funded via “a significant part” of the €2·7 billion emergency support instrument. This money is used as a down payment on the vaccines that EU member states will then purchase. Other funds are also being used to boost production capacity. The aim is to make millions, or even billions, of doses of a vaccine.103

It normally takes around 10 years to develop a vaccine. The Commission’s strategy, however, is an accelerated programme that is designed to develop the vaccine and make it available within 12–18 months.104

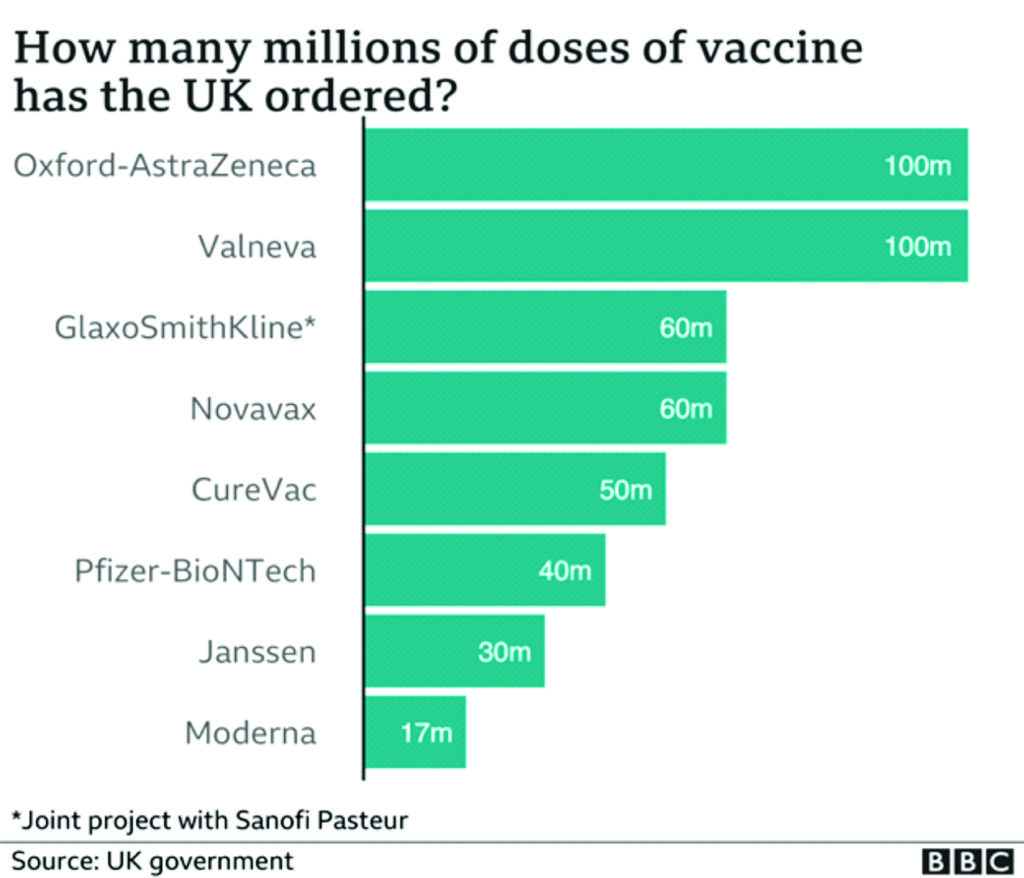

But just how accelerated is this programme? So far, the EU has concluded contracts for COVID-19 vaccines with Moderna (160 million doses), Sanofi-GSK (300 million doses), AstraZeneca (400 million doses), Johnson & Johnson (400 million doses), CureVac (405 million doses), and Pfizer–BioNTech (600 million doses). It has also had exploratory talks with the pharmaceutical companies Novavax and Valneva. However, the EMA has so far granted conditional market authorisation only to the AstraZeneca, Moderna, and Pfizer–BioNTech vaccines.105

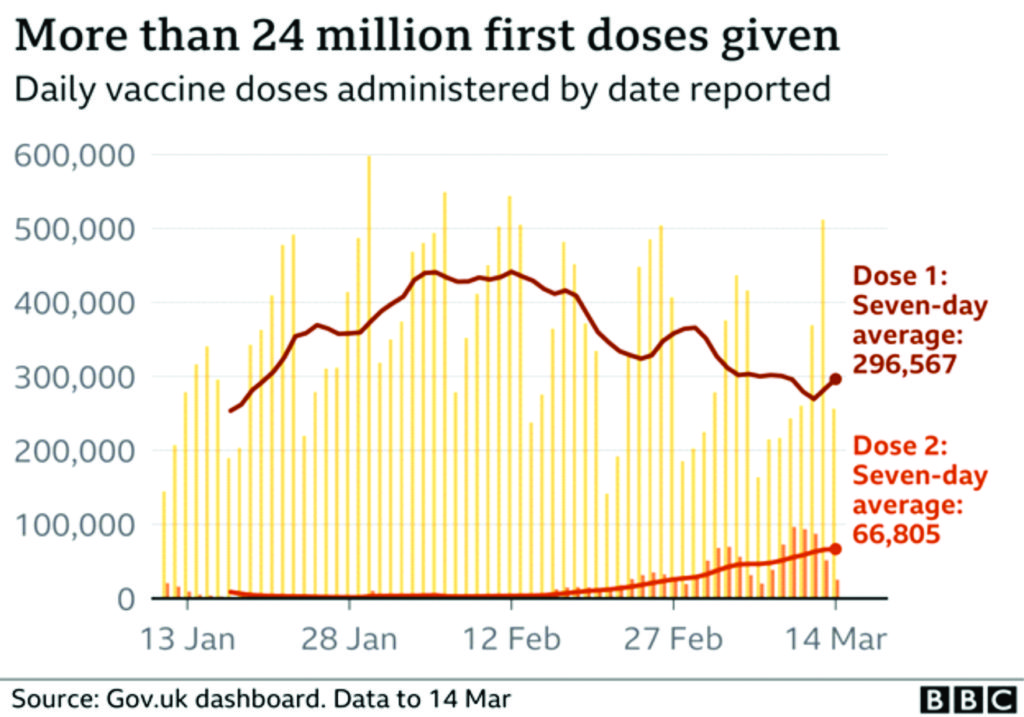

Further questions have been asked about the speed at which people are being vaccinated, particularly in comparison with the UK. The UK was the first country to approve the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, on Dec 2, 2020, and later rolled out the AstraZeneca–Oxford and Moderna vaccines. The EU, however, did not approve the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine until Dec 20. As of Feb 15, more than 15 million people in the UK had received at least one dose of the vaccine; around 23% of the population. In the EU, however, only 4·4 people per 100 000 have.106

A key explanation for the gap between the EU and UK vaccine roll-outs is down to the British–Swedish company, AstraZeneca, and the controversial vaccine procurement contacts. In summary, the UK got there first, placing an order in May, 2020, for 100 million doses. It also made sure the contracts had clear delivery dates.107

The EU signed a deal for 300 million doses of the vaccine, but not until August, 2020. Furthermore, according to reports in the German newspaper Bild, procurement expert Gerd Kerkhoff concluded the contract was “a complete disaster”. The contract had 18 “best reasonable efforts clauses”, which legally allowed the company not to deliver on agreed dates, if it said it was not able to.108

On Jan 29, 2021, the EU began trying to gain greater control over access to the vaccine. It announced that EU-based manufacturing plants, such as the Pfizer production plant in Puurs, Belgium, would now have to request authorisation to be able to export the vaccine. The EU even threatened to stop the flow of vaccine from Ireland to Northern Ireland, although this proposal was swiftly withdrawn after provoking outrage not just in London and Belfast, but also in Dublin. European media quickly slammed the Commission for threatening the Northern Ireland peace process.109

Fierce criticism of von der Leyen has also come from the usually pro-EU media in Germany—the very country which von der Leyen once served as defence minister. Die Zeit newspaper’s Alan Posener said that “if the British were still EU citizens, they would be like us: instead of having vaccinations, simply waiting for Godot”. Der Spiegel said that the EU had attempted to secure the vaccines in a “hare-brained manner, as if it were a summer sale, a bargain hunt on a whim.” Peter Tiede of the daily Bild newspaper claimed that von der Leyen had “disgraced Europe”.110

Not everyone, however, shares these views. Ellen ‘t Hoen, is a lawyer and public health advocate at research group Medicines, Laws and Policy, and is former policy director for Médecins sans Frontières’ Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines. Speaking to The Lancet, she said people should be cautious before envying the UK’s approach. “What is the UK going to gain if other countries in Europe don’t have the vaccine? It only works if you say ‘everyone for themselves’ and you build a big wall around yourself.”111

It is evident that the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine faced two major problems which come to constitute a hydra-headed monster or to be specific a Janus-faced monster: the logistic problem associated with the demand-and-supply disequilibria and the two-dose efficacy disequilibria/discrepancy. Oxford/AstraZeneca has not been able to resolve any of the problem satisfactorily. However, the saving grace so far has been that the vaccine is already on the global market shelf and is being administered in several countries outside those countries that rejected it, Through this “escape route” Oxford/AstraZeneca can recoup its losses but the damage to its reputation would be long lasting.

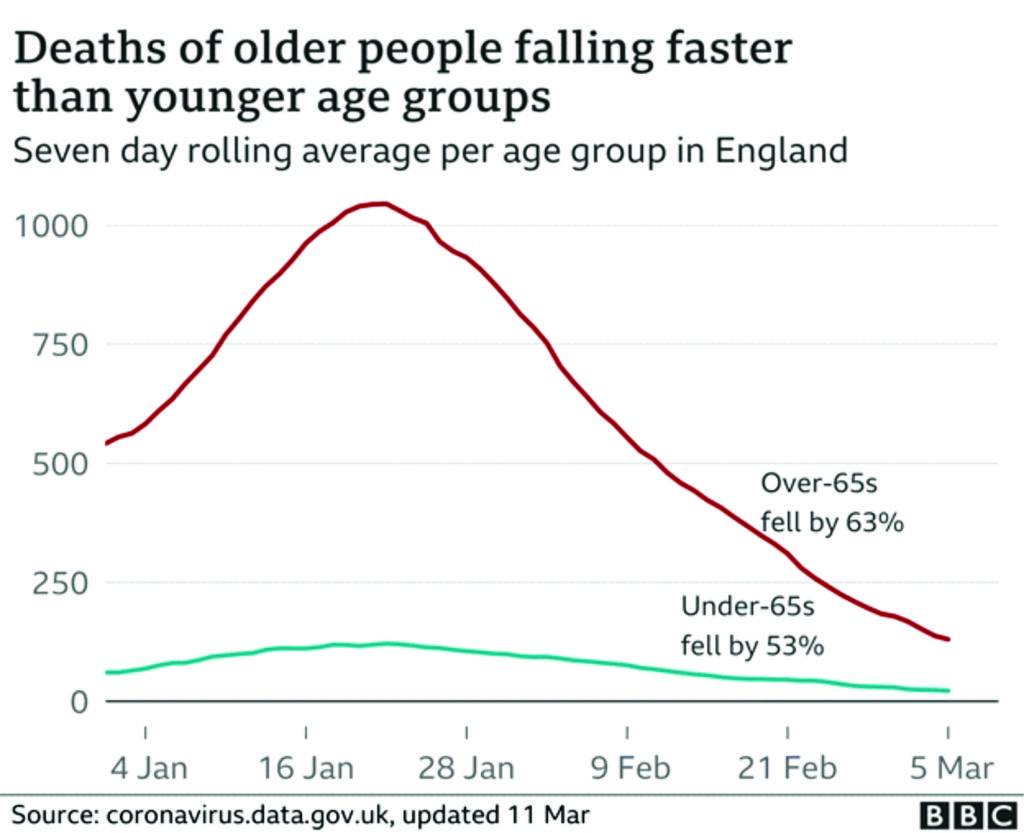

There were two further interesting pieces of research works published in The Lancet during the controversy which go to shed more light on the vaccine especially as regard the trials carried out in the United Kingdom, Brazil and South Africa about the efficacy of the vaccine on different age groups.

In early January 2021, The Lancet medical journal published an article by a group of scientists. The research was funded by UK Research and Innovation, National Institutes for Health Research (NIHR), Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Lemann Foundation, Rede D’Or, Brava and Telles Foundation, NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Thames Valley and South Midland’s NIHR Clinical Research Network, and AstraZeneca.

The aim of the report is finding “A safe and efficacious vaccine against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), if deployed with high coverage, could contribute to the control of the COVID-19 pandemic.”112

The primary objective was to evaluate the efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against NAAT-confirmed COVID-19. The primary outcome was virologically confirmed, symptomatic COVID-19, defined as a NAAT-positive swab combined with at least one qualifying symptom (fever ≥37·8°C, cough, shortness of breath, or anosmia or ageusia).113

The report evaluated “the safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine in a pooled interim analysis of four trials.”114

Findings show that: “Between April 23 and Nov 4, 2020, 23 848 participants were enrolled and 11 636 participants (7548 in the UK, 4088 in Brazil) were included in the interim primary efficacy analysis. In participants who received two standard doses, vaccine efficacy was 62·1% (95% CI 41·0–75·7; 27 [0·6%] of 4440 in the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 group vs71 [1·6%] of 4455 in the control group) and in participants who received a low dose followed by a standard dose, efficacy was 90·0% (67·4–97·0; three [0·2%] of 1367 vs 30 [2·2%] of 1374; pinteraction=0·010). Overall vaccine efficacy across both groups was 70·4% (95·8% CI 54·8–80·6; 30 [0·5%] of 5807 vs 101 [1·7%] of 5829). From 21 days after the first dose, there were ten cases hospitalised for COVID-19, all in the control arm; two were classified as severe COVID-19, including one death. There were 74 341 person-months of safety follow-up (median 3·4 months, IQR 1·3–4·8): 175 severe adverse events occurred in 168 participants, 84 events in the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 group and 91 in the control group. Three events were classified as possibly related to a vaccine: one in the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 group, one in the control group, and one in a participant who remains masked to group allocation.”115

In participants who received two standard doses, efficacy against primary symptomatic COVID-19 was consistent in both the UK (60·3% efficacy) and Brazil (64·2% efficacy), indicating these results are generalisable across two diverse settings with different timings for the booster dose (with most participants in the UK receiving the booster dose more than 12 weeks after the first dose and most participants in Brazil receiving their second dose within 6 weeks of the first). Exploratory subgroup analyses included at the request of reviewers and editors also showed no significant difference in efficacy estimates when comparing those with a short time window between doses (<6 weeks) and those with longer (≥6 weeks), although further detailed exploration of the timing of doses might be warranted.116

Efficacy of 90·0% seen in those who received a low dose as prime in the UK was intriguingly high compared with the other findings in the study. Although there is a possibility that chance might play a part in such divergent results, a similar contrast in efficacy between the LD/SD and SD/SD recipients with asymptomatic infections provides support for the observation (58·9% [95% CI 1·0 to 82·9] vs 3·8% [−72·4 to 46·3]). Exploratory subgroup analyses, included at the request of reviewers and editors, that were restricted to participants aged 18–55 years, or aligned (>8 weeks) intervals between doses, showed similar findings. Use of a low dose for priming could provide substantially more vaccine for distribution at a time of constrained supply, and these data imply that this would not compromise protection. While a vaccine that could prevent COVID-19 would have a substantial public health benefit, prevention of asymptomatic infection could reduce viral transmission and protect those with underlying health conditions who do not respond to vaccination, those who cannot be vaccinated for health reasons, and those who will not or cannot access a vaccine, providing wider benefit for society. However, the wide CIs around our estimates show that further data are needed to confirm these preliminary findings, which will be done in future analyses of the data accruing in these ongoing trials.117

In our studies, the demographic characteristics of those enrolled varied between countries. In the UK, the enrolled population was predominantly white and, in younger age groups, included more female participants due to the focus on enrolment of health-care workers. This is a typically lower risk population for severe COVID-19. The demographic profile combined with the weekly self-swabbing for asymptomatic infection in the UK results in a milder case-severity profile. In Brazil, there was a larger proportion of non-white ethnicities, and again the majority of those enrolled were health-care workers.118

We have previously reported on the local and systemic reactogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and shown that it is tolerated and that the side-effects are less both in intensity and number in older adults, with lower doses, and after the second dose. Although there were many serious adverse events reported in the study in view of the size and health status of the population included, there was no pattern of these events that provided a safety signal in the study. Three cases of transverse myelitis were initially reported as suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions, with two in the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine study arm, triggering a study pause for careful review in each case. Independent clinical review of these cases has indicated that one in the experimental group and one in the control group are unlikely to be related to study interventions, but a relationship remained possible in the third case. Careful monitoring of safety, including neurological events, continues in the trials. All safety data will be provided to regulators for review.119

In this interim analysis, we have not been able to assess duration of protection, since the first trials were initiated in April, 2020, such that all disease episodes have accrued within 6 months of the first dose being administered. Further evidence will be required to determine duration of protection and the need for additional booster doses of vaccine.120

The results presented in this Article constitute the key findings from the first interim analysis, which are provided for rapid review by the public and policy makers. In future analyses with additional data included as they accrue, we will investigate differences in key subgroups such as older cohorts, ethnicity, dose regimen, and timing of booster vaccines, and we will search for correlates of protection.121

Until widespread immunity halts the spread of SARS-CoV-2, physical distancing measures and novel therapies are needed to control COVID-19. In the meantime, an efficacious vaccine has the potential to have a major impact on the pandemic if used in populations at risk of severe disease. Here, we have shown for the first time that a viral vector vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, is efficacious and could contribute to control of the disease in this pandemic.122

In early March 2021, The Lancet medical journal published another article by the same group of scientists already mentioned above. The report is an independent research funded by NIHR, UK Research and Innovation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Lemann Foundation, Rede D’Or, the Brava and Telles Foundation, and the South African Medical Research Council.123

Their research findings reveal that “Between April 23 and Dec 6, 2020, 24 422 participants were recruited and vaccinated across the four studies, of whom 17 178 were included in the primary analysis (8597 receiving ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and 8581 receiving control vaccine). The data cutoff for these analyses was Dec 7, 2020. 332 NAAT-positive infections met the primary endpoint of symptomatic infection more than 14 days after the second dose. Overall vaccine efficacy more than 14 days after the second dose was 66·7% (95% CI 57·4–74·0), with 84 (1·0%) cases in the 8597 participants in the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 group and 248 (2·9%) in the 8581 participants in the control group. There were no hospital admissions for COVID-19 in the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 group after the initial 21-day exclusion period, and 15 in the control group. 108 (0·9%) of 12 282 participants in the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 group and 127 (1·1%) of 11 962 participants in the control group had serious adverse events. There were seven deaths considered unrelated to vaccination (two in the ChAdOx1 nCov-19 group and five in the control group), including one COVID-19-related death in one participant in the control group. Exploratory analyses showed that vaccine efficacy after a single standard dose of vaccine from day 22 to day 90 after vaccination was 76·0% (59·3–85·9). Our modelling analysis indicated that protection did not wane during this initial 3-month period. Similarly, antibody levels were maintained during this period with minimal waning by day 90 (geometric mean ratio [GMR] 0·66 [95% CI 0·59–0·74]). In the participants who received two standard doses, after the second dose, efficacy was higher in those with a longer prime-boost interval (vaccine efficacy 81·3% [95% CI 60·3–91·2] at ≥12 weeks) than in those with a short interval (vaccine efficacy 55·1% [33·0–69·9] at <6 weeks). These observations are supported by immunogenicity data that showed binding antibody responses more than two-fold higher after an interval of 12 or more weeks compared with an interval of less than 6 weeks in those who were aged 18–55 years (GMR 2·32 [2·01–2·68]).”124

The analysis presented here provides strong evidence for the efficacy of two standard doses of the vaccine, which is the regimen approved by the MHRA and other regulators. Following regulatory approval, a key question for policy makers to plan the optimal approach for roll-out is the optimal dose interval, which is assessed in this report through post-hoc exploratory analyses. Two criteria that contribute to decision making in this area are the effect of prime-boost interval on protection after the second dose and the degree to which the vaccinated individual is at risk of infection during the time period before the booster dose, if there were either reduced efficacy with a single dose or rapid waning of efficacy before the second vaccination.125

Exploratory analyses are presented in this report that show protection with dosing intervals from less than 6 weeks to 12 weeks or more and that a longer interval provides better protection after a booster dose without compromising protection in a 3-month period before the second dose is administered.126

In exploratory analyses, a single standard dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 had an efficacy of 76·0% (95% CI 59·3 to 85·9) against symptomatic COVD-19 in the first 90 days after vaccination, with no significant waning of protection during this period. It is not clear how long protection might last with a single dose because follow-up is limited to the time periods described here, and, for this reason, a second dose of vaccine is recommended.127

A second dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 induces increased neutralising antibody levels and is probably necessary for long-lasting protection. However, where there is low supply of vaccine, a policy of initially vaccinating a larger cohort with a single dose might provide better overall population protection than vaccinating half the number of individuals with two doses in the short term. With the evidence available at this time, it is anticipated that a second dose is still required to potentiate long-lived immunity. Recent modelling of delayed boosting suggests that even in the presence of substantial waning of first-dose efficacy, programmes that delay a second dose to vaccinate a larger proportion of the population result in greater immediate overall population protection.128

In our study, vaccine efficacy after the second dose was higher in those with a longer prime-boost interval, reaching 81·3% in those with a dosing interval of 12 weeks or more versus 55·1% in those with an interval of less than 6 weeks. Point estimates of efficacy were lower with shorter dosing intervals, although it should be noted that there is some uncertainty because the CIs overlap. Higher binding and neutralising antibody titres were observed in sera with the longer prime-boost interval, suggesting that, assuming there is a relationship between the humoral immune response and efficacy, these might be true findings and not artifacts of the data. Greater protective efficacy associated with stronger immune responses after a wider prime-boost interval have been seen with other vaccines such as those for influenza, Ebola virus disease, and malaria.129

The findings presented here for the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine are consistent with policy recommendations in different countries to use dose intervals of 4–12 weeks for this vaccine.130

Finally the authors declared that “It is not clear what effect each of these individual sources of variation in the data have on vaccine efficacy estimates. However, the same trend seen with efficacy is also seen in the immunological data, suggesting an underlying biological mechanism.131

Vaccination programmes aimed at vaccinating a large proportion of the population with a single dose, with a second dose given after a 3-month period, might be an effective strategy for reducing disease, and might have advantages over a programme with a short prime-boost interval for roll-out of a pandemic vaccine when supplies are scarce in the short term. Two doses of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 was efficacious in preventing symptomatic COVID-19. These results confirm those seen in the interim analysis of the trials.132

Despite these pieces of research work, several EU countries were not swayed nor persuaded by the findings of these researches. They still went ahead to impose the ban on the administration of the vaccine in their countries.

According to Rebecca Robbins and Benjamin Mueller, writing in New York Times, “[t]he announcement this week [November 23, 2020] that a cheap, easy-to-make coronavirus vaccine appeared to be up 90 percent effective was greeted with jubilation. “Get yourself a vaccaccino,” a British tabloid celebrated, noting that the vaccine, developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, costs less than a cup of coffee.133 But since unveiling the preliminary results, AstraZeneca has acknowledged a key mistake in the vaccine dosage received by some study participants, adding to questions about whether the vaccine’s apparently spectacular efficacy will hold up under additional testing.134

Scientists and industry experts said the error and a series of other irregularities and omissions in the way AstraZeneca initially disclosed the data have eroded their confidence in the reliability of the results. Officials in the United States have noted that the results were not clear. It was the head of the flagship federal vaccine initiative — not the company — who first disclosed that the vaccine’s most promising results did not reflect data from older people.135