By Alexander Ekemenah, Chief Analyst, NextMoney

“I understand the despair and frustration of so many Americans, and how they’re feeling. I understand why many governors, mayors, county officials, tribal leaders feel like they’re left on their own without a clear national plan to get them through the crisis. Let me be very clear. Things are going to continue to get worse before they get better. The memorial we held two nights ago will not be our last one, unfortunately. There are moments in history when more is asked of a particular generation, more is asked of Americans than other times. We are in that moment, now. History is going to measure whether we are up to the task. I believe we are. Next one is making sure that the National Guard and FEMA support is available. This next one is relates to expanding access to treatment for Covid-19.”

– President Joe Biden, January 2021

“We’re all SO TIRED of COVID. But there’s actually a lot of good news. Cases plummeting. Vaccines steadily rolling out, with more vaccines on the way. We just need to hang in there a few more months, and the worst will be behind us.”

– Former CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, in a tweet1

Introduction

According to Council on Foreign Relations-sponsored Independent Task Force report released in October 2020, “The United States and the world were caught unprepared by the COVID-19 pandemic despite decades of warnings of the threat of global pandemics and years of international planning. The failure to adequately fund and execute these plans has exacted a heavy human and economic price. Hundreds of thousands of lives have already been lost, and the global economy is in the midst of a painful contraction. The crisis—the greatest international public health emergency in more than a century—is not over. It is not too early, however, to begin distilling lessons from this painful experience so that the United States and the world are better positioned to cope with potential future waves of the current pandemic and to avoid disaster when the next one strikes, which it surely will.”2

The United States and indeed the rest of the world find themselves at a critical watershed point in history with the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic that originated from Wuhan city, in Hubei Province of China. Since December 31, 2019 and especially since January 2020, the world gradually came to the brink of crisis of almost complete breakdown of global health system. In most countries of the world, including the United States, the health sector for the first time in recent years came under intense pressure of being overwhelmed by the flood of patients suffering from the coronavirus pandemic. Indeed, in some countries, the health sector was so overwhelmed that it threw up philosophical dilemma or crisis of having to decide which patient to receive immediate attention while others are left unattended to – a dilemma that went straight against the entire philosophical Hippocratic oath to save all lives at whatever cost.

Unfortunately, the coronavirus pandemic chose to break out under an Administration in the United States that from all growing evidences of either willful carelessness or criminal negligence chose to fidget while the whole country was being engulfed by the pandemic, killing thousands in the process. The situation has been analogously compared to Emperor Nero of Rome making merriment while the city burns! The pandemic also broke out when the United States was also facing historic challenge from one of its global arch-rivals and contenders for global hegemonic supremacy, China, a rivalry that came under the rubric of trade and tech wars between the two countries, including disputes over South China Sea.

The pandemic also came to the United States in a presidential election year. Naturally the pandemic became a theme of the election campaign between the two contending parties and other splinter groups/stakeholders, a theme of heated and acrimonious debate. Even after the election was over and with the victory of candidates other than the incumbents in office, the pandemic was still hitting hard at the fabric of the health system with daily turnover of 100, 000 infection rate and thousands of deaths.

Then suddenly, just few days to the inauguration of a new President, the hitherto Frankenstein monster of a pandemic started slowing down. Indeed, it is generally agreed by all observers and analysts watching the unfolding epochal developments in the United States that hardly has President Joe Biden settled down in the Oval Office that the pandemic that was hitherto frightfully spreading like Prairie fire started slowing down. It is no longer news that, at last, the pandemic is on the decline.

In some quarters, this is seen as a sign of good omen of what more to expect in the next several months the more President Biden gets a firmer handle on pressing issues facing the country. But the pandemic is the biggest issue of all as at the moment, a existential crisis of immense proportion.

There are big questions, however. How did this decline actually come about within a short period of President Joe Biden settling down in office? What are the fundamental factors responsible for this indisputable decline? What happens after the flattened curve? How should the United States henceforth relate to China that gave the world this pandemic?

This article seeks to itemize the responsible factors for critical interrogation and examination.

Falling Figures

A deep dive or a telescopic view across the Atlantic Ocean presents a unique panorama of factors or variables that are now being contested as the corpus of reasons responsible for the declining coronavirus pandemic in the United States. They are being contested because there is no concrete agreement over the body of factors that might have been responsible for this decline.

Why this panorama is unique is because of what may be its likely impact across the world in relations to those countries still struggling with the pandemic. It is also unique given the background of the lacklustre performance of the previous administration which saw over three hundred thousand dead before a new administration was ushered into the Oval Office in the White House on January 20, 2021.

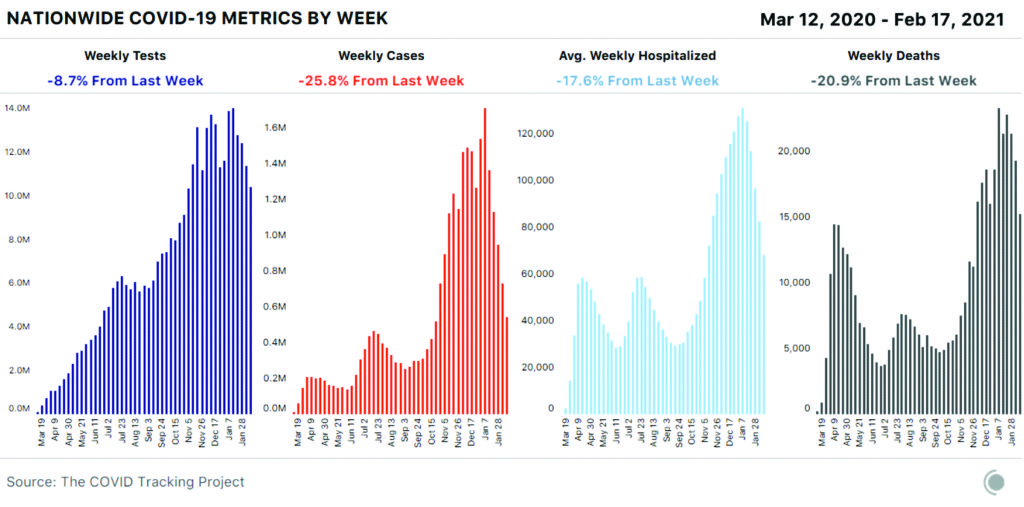

The infection rate reached its peak around mid-January 2021. According to Reiss Thebault (2021) writing in Washington Post: The rolling daily average of new infections in the United States hit its all-time high of 248,200 on Jan[uary] 12, [2021] according to data gathered and analyzed by The Washington Post. Since then, the number has dropped every day, hitting 91,000 on Sunday, its lowest level since November.3

As at January 15, 2021, just five days to the inauguration of President Joe Biden, the mortality rate has hit a hillcrest of 397,9944 But as at February 19, 2021, there have been total cases of 27,944,914 with 492,946 total deaths. In the previous two weeks, there were reported 1,092,063 confirmed cases (at -45%) with one case 299 people infected and 33,556 reported deaths (-26%)5

According to the National Geographic: New cases of the disease have declined for the fifth straight week, dropping by 23 percent. Each region of the country has also recorded “substantial declines” in hospitalizations—although the total number of people hospitalized remains higher than at the peak of previous surges last spring and summer. Deaths related to COVID-19 have also fallen by nearly 21 percent.6

As at February 22, 2021, there were reported 28,147,867 total cases with 498,654 total deaths based on 7-day and 14-day daily average. In the previous two weeks, there were 1,009,882 confirmed cases at -44% with 1 in 323 people infected and 33,718 reported deaths at -23%7

Julie Bosman and Donald McNeil of New York Times put the declining percentage at 21: “Nationwide, new coronavirus cases have fallen 21 percent in the last two weeks, according to a New York Times database, and some experts have suggested this could mark the start of a shifting course after nearly four months of ever-worsening case totals.”8

The pandemic reached its crescendo in mid-January 2021. According to The Atlantic: For 16 weeks, throughout the fall and then straight through the data disruptions around Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day, the number of people currently hospitalized with COVID-19 has risen. On October 13, there were 36,000 people with COVID-19 in U.S. hospitals. Yesterday, on January 13, there were 130,000.9 [A]fter two weeks of holiday-muddled death data, the inevitable consequence of these rising hospitalizations arrived. States reported 23,259 COVID-19 deaths this week, 25 percent more than in any other week since the pandemic began. For scale, the COVID-19 deaths reported this week exceed the CDC’s current estimate for flu-related deaths during the entire 2019–20 season.10

The decline still remains within a narrow band. There has been no siesmic shift. But the bandwidth is significant for the mere fact that it is coming on stream and is still unfolding. It has not dropped sharply or steeply but it is visibly on a downward slope. Therefore, crunching these numbers require careful attention to the state and regional fluctuations within the context of worrisome several variants of the pandemic that have emerged for which there have been no rational explanations as to the origins of these variants.

Prior to January 20, 2021, i.e. before Joe Biden was sworn in as the President, the coronavirus infection and mortality rates in the United States were the highest in the world. But the country is now seeing an encouraging decline in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. However, as at February 19, 2021, the United States still has the highest infection and mortality rates in the world. No other country has surpassed it.

COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths continue to fall as the United States recovers from the holiday surge of infections. The nation saw a 23-percent decline in cases this week (as at February 19), and on February 8, the U.S. recorded fewer than 80,000 new daily cases for the first time since late October—down from a peak of 295,000 new cases on January 8. Deaths have also declined for the second straight week, although there were still more than 19,000 lives lost this week (February 19).11

Even as cases in the Northeast part of the country have held steady during this period, new hospitalizations per capita have increased in Connecticut and New York. Also, although cases and deaths at long-term care facilities continued to drop a study published in the journal JAMA Network Open showed that COVID-19 deaths were more than three times higher in nursing homes with non-white residents.12

What become apparent was that the infection rate reached its plateau around mid-January 2021 and from there started slowly declining to its current status by end of February.13

Some of this good news can be attributed to the nationwide vaccine rollout, according to the COVID Tracking Project. Based on their data, nursing homes and long-term care facilities have recorded fewer COVID-19 deaths—and now account for a smaller percentage of U.S. deaths overall—which seems to correlate with vaccinations among this vulnerable group. In Texas, however, case counts are artificially low and vaccination has slowed as the region grapples with severe winter weather and power outages. Also, concerns remain high as coronavirus variants continue to spread across the country.14

But more significant in this scenario are the reported cases of the coronavirus variants that have more than doubled since January 31. The more contagious variant first spotted in the U.K. (B.1.1.7) has now been detected in 37 states. The variants initially spotted in Brazil (P.1) and South Africa (B.1.351) and are for the moment confined to two and five states, respectively.15

According to The Atlantic: All major indicators of COVID-19 transmission in the United States continue to fall rapidly. Weekly new cases have fallen from 1.7 million at the national peak in early January to fewer than 600,000 this week, and cases have declined in every state. As we’ve seen at many points in the pandemic, case numbers are changing most quickly, with hospitalizations and deaths declining after a delay: Cases have been falling sharply for five weeks, hospitalizations for four, and deaths for two. In this week’s numbers from nursing homes and other long-term-care facilities, we are now seeing solid declines in deaths correlated with COVID-19 vaccinations in this most vulnerable population.16

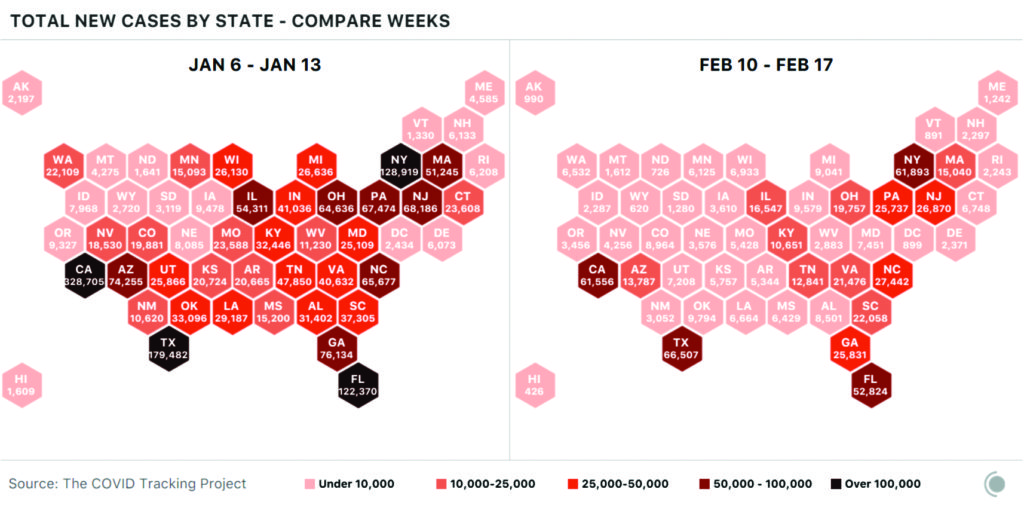

If we look at cartograms of the United States showing weekly new cases for the worst week in January and for the week ending yesterday [February 17], the drop in the number of cases in each state is startling. Although states are still reporting large numbers of cases, many more parts of the country show absolute levels much closer to what we saw before the most recent surge accelerated nationally in October.17

According to Daniel Arkin and Colin Sheeley, writing on February 15, 2021: The average number of daily new coronavirus cases in the United States fell below 100,000 Friday for the first time in months, according to an NBC News tally, but experts warn that infections remain high nationwide and Americans must continue to follow precautions to slow the spread of the virus.18 In the last 14 days, according to data compiled by NBC News, coronavirus cases have declined to varying degrees in all 50 states, as well as in Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands.18

Ten states and Puerto Rico saw a slight decrease between 10 and 25 percent. Forty states, plus the district and the Northern Mariana Islands, experienced a more significant decrease of 25 percent or more, according to the data. California, which has been hit hard by Covid-19 in recent weeks, saw a particularly dramatic decline of roughly 48 percent over the last 14 days.19

The encouraging trend lines were reflected in the average daily new cases nationwide. The seven-day average for cases dipped to 99,052 at the end of Friday — a sizeable drop from even a month ago, when the U.S. was averaging 239,284 cases a day. The seven-day average of new infections went above 200,000 for much of December and climbed to around 250,000 in January, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University.20 In another potentially encouraging sign, the U.S. recorded 779 deaths Sunday night — the first time since Nov. 29 that fewer than 1,000 people in the country have died from the coronavirus in a single day. It is worth noting, however, that single-day numbers are not good indicators of actual trends.21

Meanwhile, public health experts and top government officials have warned that the coronavirus remains a threat and precautions must remain in place. “We are still at about 100,000 cases a day. We are still at around 1,500 to 3,500 deaths per day. The cases are more than two-and-a-half-fold times what we saw over the summer,” Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said on NBC’s “Meet the Press”. “It’s encouraging to see these trends coming down, but they’re coming down from an extraordinarily high place,” she added.22 Walensky said that new variants — including one first detected in the United Kingdom that appears to be more transmissible and has already been found in more than 30 states — will likely lead to more cases and more deaths. “All of it is really wraps up into we can’t let our guard down,” Walensky said. “We have to continue wearing masks. We have to continue with our current mitigation measures. And we have to continue getting vaccinated as soon as that vaccine is available to us.”23

In total, the U.S. has recorded more than 27.7 million cases of the coronavirus and more than 487,000 deaths.24

These figures convey a tragic panorama that is as frightful as well. Oral and circumstantial evidences are now slowly emerging through off-the-cuff or slip-of-tongue statements by key officials and politicians in Trump Administration that indicated that Trump Administration did not really and sincerely intend to do anything about the coronavirus pandemic but to let it rage to the point of “herd immunity” and thus kill as many possible a citizen especially if that citizen were to be a black or any other colour.

According to this racist-oriented mindset, the many black or other colour that die the better. It was this sinister motive that was behind the lacklustre performance of Trump Administration as regard the pandemic, running from pillar to pole without achieving anything concrete. Even though former President Donald Trump called the pandemic a “Chinese” or “Wuhan” virus, he and the entire Administration never saw the pandemic as an internal or national security threat or clear and present danger but rather as an ordinary public health risk that will soon disappear on its own accord. “It is a flu that will soon go away” is the summary of the lackadaisical but sinister worldview or operational mindset of the Trump Administration towards the coronavirus pandemic. It is evilry of the greatest Darkness that sacrificed the public health and welfare of the citizens to the most selfish and narrow political expediency.

It was no longer the pandemic that was the internal or national security threat but rather the sinister worldview and mindset to let the pandemic rage and kill as many people as possible that is of the greatest danger to the security and welfare of the citizens. While China bears the moral and legal blameworthiness for starting the pandemic, it is equally important not to forget the lackadaisical attitude of an Administration that has led to death of thousands of innocent citizens who are not properly and sufficiently educated as to the danger of existential crisis posed by the pandemic. Trump Administration is guilty of this criminal negligence – for want of a better terminology to describe the political malfeasance that led to deaths of thousands of people peaking the highest in the world. For it is inconceivable how a government would be stiff-necked to treat a pandemic that threatens the foundation of public health and even public security with so much levity or kid-gloves.

There is a relevant and inescapable question here: What would have been the cumulative effects of the pandemic by now, if it was still Donald Trump that is in the White House? The scenario could not have been imagined. It would have been sheer horror. Under Donald Trump’s watch, the pandemic went from the First to Second and Third Wave/Season. The pandemic would have been heading full-blast to the Fourth Wave by now if it is Donald Trump that is still in the White House. Here it is not a question of some group of people sitting down in a secret office to engineer such a Wave. The lackadaisical attitude that has taken on an official stance would have inexorably led to it. For the GOP ardent supporters of Donald Trump and his chutzpah or hubris, this might sound or seem preposterous or prejudicial a statement to make. But it is quite possible to make a projection of the future in either short, medium or long term based on established pattern (objective facts or conditions) of the immediate past, for instance, from January 2020 to January 2021 to fact-check what Donald Trump did or did not do to halt the raging pandemic.

The Achilles Heel of the US in relation to the pandemic under Trump Administration was revealed by the Council on Foreign Relations-sponsored Independent Task Force report released in October 2020.

- The Task Force assesses the U.S. performance during the COVID-19 pandemic as deeply flawed. The United States has declared pandemics to be a national security threat but has not acted or organized itself accordingly. The federal government lacks a strong focal point and expertise at the White House for ensuring pandemic readiness and coordinating an effective response. Despite intelligence and public health warnings of an imminent pandemic, the United States did not act quickly enough in mobilizing a coherent nationwide response, wasting precious weeks that could otherwise have been used to implement a nationwide strategy and capacity for testing and contact tracing to identify new infections and reduce their spread. These failures had grievous economic and health consequences, forcing states, localities, and employers to resort to blunt interventions, including imposing severe limits on human movement and shuttering businesses and public places. Without clear federal guidance, many states relaxed these public health measures prematurely, resulting in new spikes.

- The Task Force finds that the United States compounded these early mistakes with other unforced errors on public health risk communication. Elected U.S. officials, including President Donald J. Trump himself, often fell short as communicators, failing to offer the American people clear, reliable, and science-based information about the risk of infection; to adequately defend public health officials against harassment and personal attacks; and to release timely guidance on the utility of the public health measures implemented to combat the spread of the disease.

- The pandemic also exposed the nation’s inadequate investment in state and local health systems, many of which were quickly overwhelmed. The failure to maintain an adequate Strategic National Stockpile (SNS)—and to clarify the rules governing its use—led to shortages of essential medical supplies and competition among states over scarce medical equipment. More generally, COVID-19 revealed tremendous confusion over the respective responsibilities of federal, state, local, and tribal governments, resulting in blame-shifting and an incoherent U.S. approach to this public health emergency.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed the lack of coordination in U.S. and global pandemic preparedness and response in three areas. It has illustrated the risks of overdependence on a single nation, such as China, for essential medicines and medical equipment in a global pandemic. It has exposed the lack of a multilateral mechanism to encourage the joint development and globally equitable distribution of lifesaving vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics. Finally, it has revealed the limitations of existing national and global systems of epidemic threat surveillance and assessment, which left public health officials and researchers without access to timely data.

- This pandemic has exposed the failure of the United States to invest adequately in the public health of the U.S. population or to provide sufficient protections to marginalized, at-risk, and underserved groups to prevent outbreaks from accelerating into epidemics. The Task Force recommends that the United States adopt a national policy establishing and enforcing pandemic readiness standards for hospitals and health systems and ensuring that these institutions respect and promote health equity. The CDC, in collaboration with states and localities, should make it standard practice to collect and share data on the vulnerability of specific populations, most notably Black Americans, Native Americans, Latin Americans, low-income families, and the elderly, to pandemic disease. The U.S. federal, state, and local governments should craft strategies, programs, budgets, and plans for targeted public health investments that increase the resilience of these communities, as well as nursing home residents and essential workers. The Task Force considers this a matter of both social justice and global and U.S. health security.

- No factor undercut the early U.S. response to COVID-19 more than the lack of a comprehensive, nationwide strategy and capability for testing, tracing, and isolation. To avoid a reoccurrence of those failures in future pandemics, the Task Force recommends that the United States immediately develop and adequately fund a coherent national strategy and capability to support testing and contact tracing by states and localities, following CDC guidance, that can be rapidly scaled up in any public health emergency, including by leveraging the latest digital technologies, incentivizing research and development of diagnostics such as low-cost rapid tests, and training tens of thousands of contact tracers.

- The United States cannot afford to have public health messages muddled or discounted because they are couched in partisan messaging that seeks to downplay or exaggerate the dangers the country faces or the precautions needed to address these threats. The Task Force calls on all U.S. public officials to accept, as a critical dimension of successful pandemic preparedness and a fundamental obligation of their positions, the responsibility of communicating with the American people in a clear, transparent, and science-based manner. This should include increased reliance on public health experts—including from the CDC, HHS, National Institutes of Health, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and other technical agencies—to provide briefings and timely guidance to the American people.

- To ensure that the nation possesses sufficient quantities of essential medicines and equipment in an urgent public health emergency (whether a pandemic or bioterror event), the executive branch and Congress should work together to ensure that the Strategic National Stockpile is appropriately resourced and stocked for future pandemics, and that there is no confusion between federal and state governments as to its purpose. In an extended pandemic crisis, the SNS system should be prepared to act as a central purchasing agent on behalf of state governments.

- In parallel with this step, the United States should use incentives to diversify its global supply chains of critical medical supplies and protective equipment for resilience and reliability, without unduly distorting international trade and running afoul of WTO commitments. This approach could include pursuing emergency sharing arrangements among close U.S. partners and allies and strengthening multilateral regulatory cooperation among major producer nations to ensure common standards and quality control, especially during emergencies. The FDA should produce regular updates on supply chain vulnerabilities.

- Finally, the Task Force urges the United States to support multilateral mechanisms to develop, manufacture, allocate, and deliver COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics in a globally fair manner consistent with public health needs. Absent such global coordination, countries have been bidding against one another, driving up the price of vaccines and related materials. The resulting arms race threatens to prolong the pandemic, generate resentment against vaccine-hoarding nations, and undermine U.S. economic, diplomatic, and strategic interests. The Task Force recommends that the United States work with political leaders from countries representing the majority of global vaccine-manufacturing capacity to support the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI); Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; and WHO in developing a globally fair allocation system that can be expanded for potential use in future pandemics.

- The only certain thing is that when this pandemic is brought under control, another will eventually take its place. Pandemic threats are inevitable, but the systemic U.S. and global policy failures that have accompanied the spread of this coronavirus were not. This report is intended to ensure that in future waves of the current pandemic and when the next pandemic threat occurs, the United States and the world are better prepared to avoid at least some of the missteps that have cost humanity so dearly.25

It is this evil that Biden Administration has come to correct, reverse or roll back. That day was February 18, 2021, when Biden Administration released and rolled out the National Strategy for the COVID-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness dated January 21, 2021. This National Strategy is an attestation to the commitment of Biden Administration to pass the test of history as regard defeating the deadly pandemic that has come to wreck so much havoc on American public health, economy and damage its international image and reputation.

As the Biden administration on announced a “full-scale wartime effort” to combat the virus, Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the nation’s top infectious-disease expert, said the nation’s outbreak “looks like it might actually be plateauing in the sense of turning around,” but he cautioned that the country remained in a dire situation.26

Thirty-seven states are seeing sustained reductions in cases, with only one reporting significant increases. Arizona and California, which reached disastrous new case records in recent weeks, have reported noticeable drops over the past several days. Around some Midwestern cities that drove surges of infections in the early fall, case numbers have fallen 50 percent or more from their peaks.27 Still, the country continues to average nearly 190,000 new cases each day, more than any point of the pandemic before December. Deaths from the coronavirus are still extraordinarily high, with more than 4,300 deaths announced on Wednesday, the second-highest daily total of the pandemic. And in some places, there has been no progress at all.28

Factors and Variables

So, why are cases declining so rapidly?

Dr William Schaffner an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, said there may be a variety of reasons. “Vaccinations likely are making a small contribution to the decline in COVID cases. A drop from the holiday surge and perhaps more mask wearing may be playing a role,” he told Healthline. “That said, I suspect that ‘community immunity’ (herd immunity) is starting to occur in some parts of the country due to extensive asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic transmission, and might well be the most important element producing the decline in new cases of COVID,” he said.29

Experts do have concerns that the plunging numbers are encouraging some states to lift mask mandates and some communities to reopen businesses and public facilities too quickly. “I don’t think it’s wise to lift safety measures like mask mandates. We are not yet out of the woods yet,” Dr Jamila Taylor director of healthcare reform and a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, told Healthline. “While we are making some progress in containing the virus, in addition to increasing access to testing and vaccinations, states must continue to mandate mask wearing and limit the capacity at restaurants,” she said. “This is particularly true for states that continue to experience challenges with the containment of COVID-19. With new variants increasingly spreading, I worry that loosening our precautions prematurely could end in disaster as we head into the spring and summer months,” Taylor said.30

Healio asked several infectious disease experts about these and other issues. They agreed that there is no one reason for the decline in cases.What is really driving the current downward trend in cases in the U.S.? According to Amesh A. Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security: “I think the downward trend is multifactorial and has to do with the fact that travel is back to a baseline after increases over the holiday weeks, people are being more mindful of wearing face coverings, there has been a significant proportion of people infected who have some immunity and there also may be some small contribution from vaccines.31

Cornelius (Neil) J. Clancy, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of the extensively drug-resistant pathogen lab and mycology program, University of Pittsburgh was of the view that it is “multifactorial, involving some combination of behavior (masking, distancing, restricting travel and masking, getting through the holidays, etc.), seasonality, cumulative past infections and vaccination reducing vulnerable targets and perhaps some tapering off in number of tests performed.”32

Carlos del Rio, MD, FIDSA, Infectious Disease News Editorial Board Member and executive associate dean, Emory University School of Medicine said the rapid decline in cases in the U.S. likely “has many origins. The first one is that holidays are over. We had a huge surge as a result of having Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s in rapid sequence while variants were spreading unknowingly. Now that holidays are over, people are not gathering as much, then transmission has slowed down. We are also being more careful; people are wearing masks (even double masking) because of the variants. There is also testing. Testing has gone down quite a bit, and as a result, there is less case detection. Finally, there may be starting to have an impact of vaccines, but my gut feeling is that it is too early for that.33

However, Jeanne Marrazzo, Infectious Disease News Editorial Board Member and director of the Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine said it is “complex. We have gotten far enough out from the super spreader opportunities presented by the end-of-the-year holidays, and I believe the community as a whole reacted to the peaks in December and January by escalating mask use and social distancing to a considerable extent. I would like to think that vaccination efforts in the last month are playing a role, especially in the most vulnerable people and in essential (including health care) workers, but it will take some time to figure out if that is the case. Finally, I do think that in general the level of diagnostic testing is declining as efforts shift over to ramping up vaccination. That might be contributing to a decline in case counts that isn’t necessarily an accurate reflection of true underlying disease. That said, the declines in hospitalizations are indisputable, and that is very encouraging.”34

According to Derek Thompson (2021) there are four basic reasons for the decline: social distancing, seasonality, seroprevalence and vaccines.35

These factors can only be understood if they are contextualized within the larger environment of the global tapestry. This is because at a point in time and space they were non-effective in halting the spread of the pandemic until now. The worrisome question is why and/or how?

Both the Federal and States Governments under Trump Administration have been largely criticized for allowing the pandemic to spread without taking concrete and effective steps to halt it.

For instance, the much respected scholars, Thomas Bollyky and Stewart Patrick, writing for Council on Foreign Relations accused Trump Administration and several state governments of wasting precious time in responding to the outbreak of the pandemic in the US. “The federal government and many states wasted precious weeks that could otherwise have been used to implement aggressive testing and tracing, social-distancing policies, and isolation, quarantine, and other public health interventions to dampen the rate of new infections. Two prominent epidemiologists estimate that if the government had issued social-distancing guidelines two weeks earlier in March, the United States could have cut death rates by 83 percent in the first months of the pandemic. Had the guidelines been issued just one week earlier, according to these researchers, mortality would have still dropped by 55 percent.36

Fast forward. Many state governors are now anxious to lift all restrictions and return the “system” to “Old Normal” thus subtly resisting the “New Normal” dictating facemask wearing, social distancing mandate, handwashing and sanitizing regularly, etc. These governors are not willing to enforce compliance with the restrictions based on the arguments about individual freedom of choice and/or will, forgeting in this scenario the principle of “all for one, one for all”. Most of these governors can be regarded as modern social Darwinists: tactically allowing many people to die as a result of failure to comply with elementary social and health safety measures because of their vaunted “individual freedom” or the so-called “beauty” of herd immunity that was gradually elevated to the front burner and reified into a vulgar height.

Let us examine some of the factors.

Facemask and Social Distancing

The contribution of facemask wearing and keeping of social distance to the decline of the pandemic must be taken with a pinch of salt – more so when there is no sufficient evidence of increase in facemask wearing and keeping of social distances across the states and regions in the country especially when there were evident hostile attitude towards them hitherto before now. This is one area that may be perhaps more difficult to establish the validity of their contribution to the decline. Why? Because under Trump Administration, there was not only resistance to wearing of facemasks but also keeping social distances – even inside the White House. Trump Administration did not do much to enforce these rules, if it ever did anything at all. Compliance was placed under freedom of choice which allows many citizens to avoid wearing facemask in public places.

It was only when Biden Administration came on board on January 20, 2021 that wearing of facemask became mandatory on all Federal properties, airlines and buses. There was leading by example in which case we see President Joe Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris and other high government officials wearing facemask both in the White House and other public places.

As at the time of writing this, it is barely a month that President Biden took over the reign of government. How facemask wearing and keeping social distance could have suddenly resulted in cumulative contribution to the decline of the pandemic is still largely inexplicable. It cannot be ascertained. There is no data and statistics on the level of compliance with facemask wearing and keeping of social distances resulting into decline of the spread of the pandemic.

This notion probably lie in the realm of general observation. There are no scientific proofs to back up this notional argument. Facemask wearing and keeping of social distances are generally regarded as preventive measures – not cure. It does not in the final analysis actually prevent contracting the pandemic through any of the known channels or vectors. There are even rhetorical questions: Are people just wearing facemask and keeping social distances? Why were they not effective before January when the pandemic started to visibly nose-dive in its spread? Are citizens suddenly wearing more facemask and keeping social distance in January 2021 than the entire previous year?

For those countries that have since early 2020 defeated the pandemic especially in the Mekong-Pacific region, there have been no body of scientific or medical evidences of the medical role played by wearing of facemask and keeping social distancing in the defeat of the pandemic. There were even no mass vaccination because at any rate there was no known vaccine readily available at this point in time. Rather, it was a combination of early rapid response involving contact tracing, testing, deployment of smart technology and sophisticated medical facilities. The role of sheer commitment of the political leadership in these countries, their evident refusal to play politics with public health safety issues and enforcement of volitional “force of will” remain indisputable in the entire matrix of the factors responsible for defeating the pandemic in these countries.

There are even countries like Afghanistan, Mongolia, Tibet and the Himalayan region that recorded near zero infection and casualty rates. There was no reported mass-scale wearing of facemask and keeping of social distances in these countries. There were no vaccinations. In these countries, it was business of daily life as usual, mostly struggling to survive economic hardship. Nothing more. For those countries like Nigeria, Senegal and several other sub-Saharan African countries that recorded comparatively low infection and mortality rates, wearing of facemask and keeping social distances have not been cited exclusively in any scientific research as part of the corpus of reasons for the declining pandemic in this category of countries.

Yet this cannot be completely ruled out as possible factors that are now argued to be helping to crunch down the infection and mortality rates in the US. Some analysts even elevated it to the top of the list in the taxonomy of the reasons for the decline. “If I were ranking explanations for the decline in COVID-19, behavior would be No. 1,” says Ali Mokdad, a global-health professor at the University of Washington, in Seattle. “If you look at mobility data the week after Thanksgiving and Christmas, activity went down.”37

Other officials have pointed to Google mobility data to argue that Americans withdrew into their homes after the winter holidays and hunkered down during the subsequent spike in cases that grew out of all that yuletide socializing. New hospital admissions for COVID-19 peaked in the second week of January—another sign that social distancing during the coldest month of the year bent the curve.38

Our cautious behavior evidently requires the impetus of a terrifying surge. In the spring, southern and western states thought they had avoided the worst of the early wave, and governors refused to issue mask mandates. Then cases spiked in Texas, Florida, and Arizona, and mask-wearing behavior in the South increased. When cases came down again, people relaxed, cases went up again, and the awful do-si-do continued.39

There is no doubt that the ordinary American attitudinal posturing towards the pandemic can be considered bizzare. Americans can be said to not have taken the pandemic serious enough especially keeping themselves safe from it. They were haughty towards it. They cherish their freedoms in form of age-old social habits more than anything else which have become idolatry for them. They do not see the pandemic as a veritable danger to their freedoms and that the only way they can overcome the pandemic is by abating their freedoms temporarily – which in the final anlysis is a protective shiled for these same freedoms in the collective sense of it. American behaviour was aided and abetted by an Administration in the White House that do not even consider the pandemic enough grave threat to public health safety or security.

Overall, the peg of this factor is very vulnerable. It is made of weak material substance that made it structurally unstable. Mobility reduced across the country and between the US and other countries due to restrictions placed on air travel especially. But reduction in mobility is not equivalent by any stretch of imagination with full compliance with facemask wearing and keeping of social distances especially when it comes to travelling cross-country through road transportation or train.

Seroprevalence

This is perhaps the most tricky of all the factors

Since this first case of COVID-19, several seroepidemiologic investigations have been conducted to understand the spread of asymptomatic and subclinical infections in the general population.40 Additionally, seroprevalence studies offer greater insight into how effective containment strategies, such as social distancing and quarantines, are working to control transmission rates.41

Many seroprevalence studies conducted across the world have shown that the number of undiagnosed, missing cases is probably greater than confirmed cases.42 In a study published in the JAMA of Internal Medicine, investigators collected serum samples from 16,025 geographically diverse individuals in the United States between March 23 through May 2020. There was no evidence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in most specimens. The adjusted estimates of the percentage of people who were seroreactive to the spike protein antibodies of SARS-CoV-2 were between 1.0% in people from San Francisco to 6.9% in people from New York City.43 The study also found that the estimated number of COVID-19 infections were between 6 to 24 times higher than the number of reported cases. According to the researchers, their results may be explained by individuals who had mild disease or no symptoms who did not seek medical attention or undergo testing. These people, however, likely contribute to a viral transmission.44

In another cross-sectional study from Korea, researchers tested the seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in outpatients. The goal of the study was to understand the burden of COVID-19 as well as the level of herd immunity in this population. In total, the study included 1,500 serum samples which were obtained from outpatients who attended two hospitals between May 25 and May 29 in southwestern Seoul, Korea.45 Using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay to detect immunoglobulin G (IgG), among other antibodies, against SARS-CoV-2, the investigators found an overall 0.07% anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody seropositivity. According to the researchers, this low seroprevalence indicated that the pandemic, at least in certain regions in Korea, was under control via its social distancing and contact tracing programs in place.46 Based on the findings from these studies, many scientists, clinical researchers, and governing bodies suggest proposed approaches to achieve herd immunity, such as through natural infection, is highly unethical. Additionally, professionals indicate suggest achievement of herd immunity may also be unachievable, based on current data. Effective and safe COVID-19 vaccines and therapies may be the priority approach for the pandemic.47

[Furthermore] Testing for severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes Covid-19, is complex and politically sensitive. Seroprevalence studies use antibodies as markers of pathogen exposure to estimate the proportion of the population that has been infected.48

Considerable variation has been observed in the results of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence studies. A recent survey in Spain suggested that a small fraction of the population was seropositive, despite the country being severely affected by the virus. However, within-individual variation has been observed in immune responses to viral exposure, particularly in those with mild or asymptomatic disease. For example, a pilot study from the Karolinska Institute found the percentage of people mounting T cell responses after mild covid-19, asymptomatic disease, or exposure to infected family members, consistently exceeded the percentage mounting detectable IgG serological responses against the virus. Such discordant results could have major implications for epidemiological modelling of disease transmission and herd immunity.49

Seroepidemiological studies may underestimate the true seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 for several reasons. Accuracy demands the use of an assay sensitive enough to reliably detect antibody responses to mild infection across different post-exposure scenarios. The selection of target antigen is critical, with recent data showing that the trimeric spike glycoprotein offers superior detection to the nucleocapsid in people with low level antibody responses.4 Of the 24 serological diagnostic tests that the FDA initially authorised for emergency use, six consider only the nucleocapsid, including high throughput tests in widespread use.50

The nature of the pandemic means that tests have been evaluated mostly on people who experienced severe covid-19 symptoms. Recent evidence describes a clear link between the magnitude of serological responses and severity of illness. This implies that unless assay performance is also assessed in mild and convalescent cases, the threshold for a positive result may be too high, resulting in missed community cases.51

Other problems with test calibration include the effect of demographic factors such as age, sex, and ethnicity on antibody responses and hence assay results, and the effect of timing, since early testing before seroconversion may result in false negative results. Preliminary reports showing rapid decline in virus specific IgG levels suggest that testing too late may also miss cases.52

Test performance is also influenced by the choice of antibody. Of the FDA authorised tests, most detect only IgG and IgM antibodies, the dominant components of the bloodborne antibody response. But IgA also has an important role in the immune response to respiratory tract infections and seems immunologically relevant in covid-19, particularly in asymptomatic people.53

Seroprevalence is also an excellent evaluation of the prevention measures of the health care staff. In general, the measurement of seroprevalence in Spain and Italy showed a much higher prevalence of the health care personnel, indicating a weakness in prevention measures as well as their high risk. In Marseilles, the percentage of positive test results among health care staff in direct contact remained very low in May 2020, at 3.5% (Edouard et al., 2020), due to the importance of the protective measures deployed. As a matter of fact, we had to import protective artifacts directly from China, as no stock was available in France. All in all, this work opens the door to a more general reflection on the conduct of epidemiological studies to refine the consequences of social or protective measures in the spread of the virus in a given site.54

In a study carried out by Luca Piccoli, Paolo Ferrari, Giovanni Piumatti, et all (2021) the researchers found out “that nearly 10% of HCWs developed SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies, and that while the direct contact with patients was associated with a higher risk of infection, the reorganization of the health system per se was not.” after conducting, in spring 2020, “a study to assess seroprevalence and risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection associated to hospital reorganization in 4726 HCWs employed in acute care hospitals in Southern Switzerland, a region which was severely affected by COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic.”55

The relatively low seroprevalence observed in our HCW cohort is consistent with the one reported in similar studies in 3056 HCWs at a single hospital in Belgium (6.4%) and in 40,329 HCWs in the greater New York City area (13.7%), while other studies in 2004 HCWs at an integrated care organization in London, UK, and in 2590 HCWs at a teaching hospital in Madrid, Spain reported much higher seroprevalences (up to 31.6%)56

We studied the impact of the reorganization of acute care hospitals on risk of infection in HCWs. We found that SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies were up to 75% more likely in HCWs in direct contact with COVID-19 patients, compared to those not exposed to COVID-19 patients. This is not consistent with evidence from a study conducted in a Belgian hospital, in which neither being directly involved in clinical care nor working in a COVID-19 unit increased the odds of being seropositive. However, the overall seroprevalence and the proportion of doctors and nurses in our sample (67.1%) were higher compared to the Belgian sample (51.4%). Moreover, the seroprevalence among frontline workers was less than double the one observed among administrative, service, and maintenance staff, which is consistent with evidence from a recent study conducted in HCWs in Denmark.57

Some limitations of this study are worth noting. The reorganization of health services implies that the likelihood of exposure to COVID-19 patients, and the enforcement of PPE and other preventive measures varied across the study sites. Next, despite the very large sample, response rate was overall around 65% of the eligible HCWs. However, response rates were not differential across hospital site, ward/ unit type, and HCWs category (i.e. the three main exposures to risk of infection). We did not explore the reasons for not participating, but it is unlikely that the study cohort is an overrepresentation of staff who were not exposed to or did not develop detectable antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, because while through data collection and blood sampling 12.6% of the staff was on sick leave, only 2.2% was due to COVID-19 related illness or quarantine. Moreover, participation rate was highest (82%) in frontline HCWs, which might contribute to a slight over rather than under estimation of the true seroprevalence. Conversely, because we conducted the study during the first wave of the pandemic, latency in seroconversion may have contributed to an underestimation of the true rates of infection in HCWs, because testing might have been performed too early. Indeed, 90 HCWs had detectable SARS-CoV-2 IgM but not IgG antibodies. The former develop (and decay) earlier than the latter, and including IgM positive subjects, the overall seroprevalence would reach 11.5%. A follow-up sampling is under way to ascertain whether seroprevalence increased with time in our cohort. Finally, recall and social desirability biases in the reporting of symptoms by participants cannot be excluded. However, this seems unlikely, and information bias is likely low also because of the high health literacy and level of awareness of COVID-19 in a sample of HCWs who were well aware of being at the forefront of the societal response to the epidemic during the lockdown months.58

In conclusion, our results suggest that in a region struck extremely hard during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 IgG seroprevalence in HCWs may be lower than feared and expected. Higher availability of PPE, stringent adherence to hand hygiene and physical distancing rules could explain the contained viral transmission within hospitals. Health services reorganization, while effective in streamlining and managing the high burden of COVID-19 patients requiring hospital admission, was not a major contributor in minimizing the risk of infection based on serological data among HCWs. Further studies are needed to assess whether these results are representative of other hospitals to help guide better infection control practices.59

In mid-May 2020, Wuhan launched a population-scale city-wide SARS-CoV-2 testing campaign, which aimed to perform nucleic acid and viral antibody testing for citizens in Wuhan. Here we show the screening results of cluster sampling of 61 437 residents in Wuchang District, Wuhan, China.60

A total of 1470 (2.39%, 95% CI 2.27–2.52) individuals were detected positive for at least one antiviral antibody. Among the positive individuals, 324 (0.53%, 95% CI 0.47–0.59) and 1200 (1.95%, 95% CI 1.85–2.07) were positive for immunoglobulin IgM and IgG, respectively, and 54 (0.08%, 95% CI 0.07–0.12) were positive for both antibodies. The positive rate of female carriers of antibodies was higher than those of male counterparts (male-to-female ratio of 0.75), especially in elderly citizens (ratio of 0.18 in 90+ age subgroup), indicating a sexual discrepancy in seroprevalence. In addition, viral nucleic acid detection using real-time PCR had showed 8 (0.013%, 95% CI 0.006–0.026) asymptomatic virus carriers. (Ibid) The seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan was low. Most Wuhan residents are still susceptible to this virus. Precautions, such as wearing mask, frequent hand hygiene and proper social distance, are necessary before an effective vaccine or antiviral treatments are available.61

Taiwan has been efficacious in countering the current global COVID-19 epidemics, with only 489 confirmed cases and 7 deaths, accounting for 2•07 and 0•03 per 100,000 of the general population, respectively, as of September 2, 2020. However, the potential risk for asymptomatic infections and the prevalence rates of COVID-19 remain unknown. We searched PubMed for peer-reviewed articles and preprint reports on “seroprevalence”, “SARS-CoV-2 antibody”, “anti-SARS-CoV-2”, and similar terms, up to August 31, 2020. There were only a few and most serological studies focused on specific subpopulation in “hotspot” regions of the world. Additionally, in most serological studies only one single type of laboratory test was performed, which might generate more false positive results and over-estimate the prevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.62

This is the first study that establishes an algorithm for COVID-19 serology test composed of two integrated platforms and screens the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in a significant number of individuals to accurately estimate the COVID-19 seroprevalence in Taiwan. Additionally, our testing dates were grouped into two separate weekly periods, one in May and one in July, to investigate the temporal variability of COVID-19 seroprevalence; no increase of seroprevalence rates was observed in the second weekly period.63

Our findings reveal a 0•05% seroprevalence of COVID-19 in Taiwan, which is a relatively low seroprevalence observed compared to other countries worldwide. Also, there is no increase of anti-SARS-CoV-2 detection rate 7 to 10 days after a long weekend holiday full of indoor and outdoor social activities all around the island, indicating that epidemic prevention measures in Taiwan currently are appropriate and effective. The low seroprevalence of COVID-19 in Taiwan, found in our study, helps evaluate the population proportion of the suspected asymptomatic infection and provide information for making public policies to manage the possible next wave of COVID-19 pandemics.64

Serological antibody testing is a more suitable assay for screening and estimating the prevalence of the disease, and helping make public policies for the infection control. Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 can be successfully detected from patients approximately one week after the infection. Serologically detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies provides evidence of a previously infected population as well as information regarding how many asymptomatic cases may have occurred. Compared to RT-qPCR assays, the antibody detection assays are more advantageous with faster turn-around time, higher throughput and less workload.65

Taiwan has been rather successful in countering the current COVID-19 outbreak, with only 489 confirmed cases (2.07 per 100,000) and 7 deaths (0•03 per 100,000), respectively, accounting for 0•0019% and 0•0008% of the global total as of September 2, 2020. With experiences from SARS epidemics, Taiwan was able to quickly and efficiently carry out strategies fighting against COVID-19. In January, before the outbreak of COVID-19, Taiwan had already commenced airport and onboard quarantine measures for passengers who arrived from Wuhan or transited through China, Hong Kong, and Macau. Hospitals activated negative pressure isolation wards and public places were requested to provide body temperature monitoring and hand sanitizers. In March, the Taiwan government implemented a series of strict epidemic prevention policies, including international travel restriction, wearing surgical masks and maintaining social distance. Effective policies and decent public health education protected Taiwan from community transmission [13]. However, the potential risk for asymptomatic infections and the prevalence rates of COVID-19, which are critical for Taiwan’s epidemic prevention actions, remain largely unknown.66

However, in our study, the estimated seroprevalence was 0•05%, implying that approximately 11,800 adults might have anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, which is substantially 24-fold greater than the case number of confirmed COVID-19 in Taiwan. Given the above experimental data and calculative information, a large proportion of Taiwanese people might have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus, however, most of them were asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic and not qualified for a diagnostic viral nucleic acid test. The etiological mechanisms of this subclinical manifestation of COVID-19 remain enigmatic and await further investigation. Noteworthy, compared with reports in the literature, the seroprevalence of 0•05% in Taiwan is significantly lower than that in most regions of the world and there is no increase of detection rate 7 to 10 days after a long weekend holiday full of social activities all around the island, indicating that epidemic preventions nowadays in Taiwan are appropriate and effective.67

The risk along with serological anti-SARS-CoV-2 assays for population screening is the possibility of false-positive results, which might lead to the erroneous assumption of past or present infection and subsequently putative immunity, which may place the individual into a hazardous situation of acquiring or transmitting COVID-19.68

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first small-scale population study in which a serology testing algorithm for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was established and a significant number of domestic residents were screened for the presence of antibodies to estimate the seroprevalence of COVID-19 in Taiwan. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, Taiwan government has implemented effective policies to protect Taiwan from community transmission. However, without widely screening for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, we are not able to assess the epidemiology of COVID-19 in Taiwan.69

The results in the present study reveal a 0•05% seroprevalence of COVID-19 in Taiwan, which may help evaluate the prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and provide valuable information for government’s decision making to adapt plans for facing challenges from the possible next pandemic to come.70

Serum samples from 316 healthcare workers of the University Hospital Essen, Germany were tested for SARS-CoV-2-IgG antibodies. A questionnaire was used to collect demographic and clinical data. Healthcare workers were grouped depending on the frequency of contact to COVID-19 patients in high-risk-group (n = 244) with daily contact to known or suspected SARS-CoV-2 positive patients, intermediated-risk-group (n = 37) with daily contact to patients without known or suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection at admission and low-risk-group (n = 35) without patient contact.71

In 5 of 316 (1.6 %) healthcare workers SARS-CoV-2-IgG antibodies could be detected. The seroprevalence was higher in the intermediate-risk-group vs. high-risk-group (2/37 (5.4 %) vs. 3/244 (1.2 %), p = 0.13). Four of the five subject were tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 via PCR. One (20 %) subject was not tested via PCR since he was asymptomatic. (Ibid) The overall seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare workers of a tertiary hospital in Germany is low (1.6 %). The data indicate that the local hygiene standard might be effective.72

The seroprevalence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was examined among 105 healthcare workers (HCWs) exposed to four patients who were laboratory confirmed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. These HCWs were immediately under quarantine for 14 days as soon as they were identified as close contacts. The nasopharyngeal swab samples were collected on the first and 14th day of the quarantine, while the serum samples were obtained on the 14th day of the quarantine. With the assay of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and microneutralization assay, 17.14% (18/105) of HCWs were seropositive, while their swab samples were found to be SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative. Risk analysis revealed that wearing face mask could reduce the infection risk (odds ratio [OR], 0.127, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.017, 0.968), while when exposed to COVID-19 patients, doctors might have higher risk of seroconversion (OR, 346.837, 95% CI 8.924, 13479.434), compared with HCWs exposed to colleagues as well as nurses and general service assistants who exposed to patients. Our study revealed that the serological testing is useful for the identification of asymptomatic or subclinical infection of SARS-CoV-2 among close contacts with COVID-19 patients.73

With particular reference to the United States, in a literature review carried out by Chih-ChengLai, Jui-Hsiang Wang and Po-Ren Hsueh, it was found that “The seroprevalence can vary across different sites and the seroprevalence can increase with time during longitudinal follow-up. Although healthcare workers (HCWs), especially those caring for COVID-19 patients, are considered as a high-risk group, the seroprevalence in HCWs wearing adequate personal protective equipment is thought to be no higher than that in other groups. With regard to sex, no statistically significant difference has been found between male and female subjects. Some, but not all, studies have shown that children have a lower risk than other age groups. Finally, seroprevalence can vary according to different populations, such as pregnant women and hemodialysis patients; however, limited studies have examined these associations. Furthermore, the continued surveillance of seroprevalence is warranted to estimate and monitor the growing burden of COVID-19.74

In the USA, SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody testing using a lateral flow immunoassay test (Premier Biotech) was performed on the residents of Los Angeles County, California, or within a 15-mile (24-km) radius, between April 10 and April 14, 2020. Overall, 35 of the 863 adults included tested positive, with an unadjusted prevalence of 4.06% (exact binomial CI 2.84–5.60%). After adjusting for test sensitivity and specificity, the unweighted and weighted prevalence rates of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were 4.34% (bootstrap CI 2.76–6.07%) and 4.65% (bootstrap CI 2.52–7.07%), respectively.75

In the San Francisco Bay Area, the seroprevalence was tested using the Architect SARS166 CoV-2 anti-nucleocapsid protein IgG and was found to be only 0.1% in 1000 blood donors in March 2020.76

In New York, a total of 15,626 adult residents with complete data were tested from April 19 to April 28, 2020. Of the included residents, 15,101 (96.6%) had suitable specimens, of which 1887 (12.5%) were reactive and 340 (2.3%) were indeterminate. After weighting, 12.5% were estimated to be reactive, and after further adjustment for test characteristics, the estimated cumulative incidence was 14.0% (95% CI 13.3–14.7%.77

The largest study was conducted in several regions, including San Francisco Bay Area, California, Connecticut, South Florida, Louisiana, Minneapolis-St Paul (St Cloud metro area), Minnesota, Missouri, New York, Philadelphia metro area, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Western Washington State from March 23 to May 12, 2020. A validated SARS-CoV-2 spike protein ELISA was used to test 16,025 persons, and the results showed that the adjusted estimates of seroprevalence ranged from 1.0% in the San Francisco Bay Area (collected April 23–27, 2020) to 6.9% in persons in New York City (collected March 23–April 1, 2020).78

In Indiana, the seroprevalence among 3658 randomly selected non-institutional participants was 1.01% (n = 38) between April 25 and April 29, 2020. In Oregon, the overall seropositivity was 1.0% (n = 9) among 897 participants from 19 facilities participating in the Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network. In Blaine County, 208 out of 917 adult residents had positive anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG and the overall seroprevalence was 22.7% between May 4 and May 9. The highest seroprevalence was found to be 31.5% among 200 asymptomatic residents in Chelsea, Massachusetts.79

In summary, the reported seroprevalence ranged from <0.1% to more than 20% in the different regions and could increase with time. Regular monitoring of the seroprevalence at each site should be indicated to establish the epidemiology of COVID-19.80

From the above cross-sectional review of literature and research publications, it is obvious that it is very hasty to jump to the conclusion that seroprevalence has helped to slow down the pandemic in the United States or elsewhere where there have been no previous researches to justify this assertion. While seroprevalence studies have helped reveal the biological ecosystems of people (care health workers for instance) inadvertently exposed to the coronavirus in different geographic locations across the world, their resitance or immunity levels, these studies have not shown precisely how seroprevalence has in any way helped to slow down the circulation or spread of the coronavirus. There were no body of preponderant evidences of people previously exposed to other types of epidemic or pandemic that serves as antibodies or immunity to the current coronavirus pandemic. The figures obtained from these seroprevalance studies, for instance, in Japan did not indicate their relationship to the low infection and mortality rates in Japan as a whole.

However, there is probably no doubt that seroprevalence studies could help to map out strategies and the required policy actions adapted to the requirement of particular population cohort or group, it is also understood as a fundamental point that pandemic such as coronavirus is a universal phenomenon in its nature that have different impacts in its nature across all populations. Many researches are in general agreement with the possibility of seroprevalence studies being used to fashion out policy instruments to prevent the spread of the pandemic – but not seroprevalence per se slowing down the spread of the disease.

Thus to assert that seroprevalence might have helped to slow down coronavirus in the US seems to be a preposterous statement.

Vaccination

Vaccination has also been identified as one of the factors helping to slow down the spread of the pandemic. Increasing vaccination has no doubt contributed to the slowing down of the pandemic in spite of the reported side-effects of some of the vaccines. Many vaccines have come on stream, something which was slow in coming during the time of Trump Administration that can now be attributed to the high-tension wire politics underlining manufacturing and distribution of the vaccines by Big Pharma companies. Thus during Trump Administration era, vaccination was something it was not willing to touch even with a long pole, stammering a lot of incomprehensible grammars to excuse why vaccination has not taken off on a full scale before leaving office in disgrace.

There is, however, non-availability of sufficient data and statistics to buttress the contribution of vaccination to the decline of the pandemic. Which of the vaccines has been identified as being more effective and has contributed to the declining rate of pandemic victims? What is the spread of this vaccination exercise among the states and regions and the specific locations of the decline linked with specific vaccines? Why is there still subtle resistance to the vaccination exercise in some places?

There is no doubt that the vaccination is progressing in the country. However, the U.S. has been acknowledged to be still far behind several other countries in getting its population vaccinated. Providers in the U.S. are administering about 1.3 million doses of Covid-19 vaccines per day, on average. Almost 30 million people have received at least one dose, and about 7 million have been fully vaccinated. As at February 15, it was reported that nearly “40 million people have received at least their first dose of a coronavirus vaccine, about 12 percent of the U.S. population. Experts have said that 70 percent to 90 percent of people need to have immunity, either through vaccination or prior infection, to quash the pandemic. And some leading epidemiologists have agreed, saying that not enough people are vaccinated to make such a sizable dent in the case rates.81

Researchers at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation are among those who attribute declining cases to vaccines and the virus’s seasonality, which scientists have said may allow it to spread faster in colder weather.82 In the IHME’s most recent briefing, the authors write that cases have “declined sharply,” dropping nearly 50 percent since early January. “Two [factors] are driving down transmission,” the briefing says. “1) the continued scale-up of vaccination helped by the fraction of adults willing to accept the vaccine reaching 71 percent, and 2) declining seasonality, which will contribute to declining transmission potential from now until August.”83

While agreeing that Americans are now probably reaping the fruits of their good behavior – and not much due to increased vaccinations, a former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Tom Frieden, in an interview with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria GPS was of the view that “It’s what we’re doing right: staying apart, wearing masks, not traveling, not mixing with others indoors.” “I don’t think the vaccine is having much of an impact at all on case rates,” Tom Frieden asserted.84

The current CDC director, Rochelle Walensky, [similarly] said in a round of TV interviews that behavior will be crucial to averting yet another spike in infections and that it is far too soon for states to be rescinding mask mandates. Walensky also noted the declining numbers but said cases are still “more than two-and-a-half-fold times what we saw over the summer.” “It’s encouraging to see these trends coming down, but they’re coming down from an extraordinarily high place,” she said on NBC’s “Meet the Press.”85

A fourth, less optimistic explanation has also emerged: More new cases are simply going undetected. On Twitter, Eleanor Murray, a professor of epidemiology at Boston University School of Public Health, said an increased focus on vaccine distribution and administration could be making it harder to get tested. “I worry that it’s at least partly an artifact of resources being moved from testing to vaccination,” Murray said of the declines.86

The Covid Tracking Project, which compiles and publishes data on coronavirus testing, has indeed observed a steady recent decrease in tests, from more than 2 million per day in mid-January to about 1.6 million a month later. The latest updates blames this dip on “a combination of reduced demand as well as reduced availability or accessibility of testing.” “Demand for testing may have dropped because fewer people are sick or have been exposed to infected individuals, but also perhaps because testing isn’t being promoted as heavily,” the authors write. They note that a backlog of tests over the holidays probably produced an artificial spike of reported tests in early January, but that even when adjusted, it’s still “unequivocally the wrong direction for a country that needs to understand the movements of the virus during a slow vaccine rollout and the spread of multiple new variants.”87

Derek Thompson raised a critical point in connection with vaccination.

COVID-19 cases started falling in January, when almost nobody outside of the health-care industry had been vaccinated. So vaccines probably don’t help us understand why the plunge started. But they can tell us a bit more about why the decline in hospitalizations has accelerated—and why it’s likely to continue.88

The vaccines—especially the synthetic-mRNA vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—are highly effective at preventing infection. But preventing infection is not all they do. Among those infected, they also reduce symptomatic illness. And among those with symptoms, they reduce long-term hospitalization and death to something like zero. A vaccine is not just one line of immunological defense, but several—a high wall protecting a castle and, to fight the few who bypass the wall, a group of castle defenders holding vats of searing-hot tar to pour all over the invaders. (Research indicates that some vaccines, such as AstraZeneca’s, lose their efficacy in the presence of coronavirus variants, but others, such as Pfizer’s, seem to provide potent protection. More research is necessary to say anything certain about how the vaccines protect against serious illness caused by the more contagious new strains.)89

A bit of back-of-the-envelope math shows why this period of declining hospitalizations should keep going. Let’s assume the CDC is correct that about 25 percent of adults have COVID-19 antibodies from a previous infection. Let’s add to that number the 10 percent of adults who have received vaccine shots since December, assuming an overlap of 3 percent. That would mean one-third of adults currently have some sort of protection, either from a previous infection or from a vaccine. At our current vaccination pace, we’re adding about 10 million people to this “protected” population every week. We’re accelerating toward a moment, sometime this spring, when half of American adults should have some kind of coronavirus protection. And we should be particularly optimistic about severe illness among older Americans, since the vaccines are disproportionately going to people over 50, who have accounted for 70 percent of all hospitalizations.90

That’s a lot of messy arithmetic. But the upshot is simple: Even if the rise of new variants slows the decline in cases, it is unlikely to lead to a sharp rise in mortality and hospitalizations. Although the pandemic isn’t over, we have perhaps reached the beginning of the end of COVID-19 as an exponential, existential, and mortal threat to our health-care system and our senior population.91

The role of COVID-19 vaccines may ultimately be more akin to that of the flu shot: reducing hospitalizations and deaths by mitigating the disease’s severity. The COVID-19 vaccines as a whole are excellent at preventing severe disease, and this level of protection so far seems to hold even against a new coronavirus variant found in South Africa that is causing reinfections. This, rather than herd immunity, is a more achievable goal for the vaccines. “My picture of the endgame is we will, as fast as we can, start taking people out of harm’s way” through vaccination, says Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at Harvard. The virus still circulates, but fewer people die.92

Seasonality

According to Derek Thompson “Behavior can’t explain everything. Mask wearing, social distancing, and other virus-mitigating habits vary among states and countries. But COVID-19 is in retreat across North America and Europe. Since January 1, daily cases are down 70 percent in the United Kingdom, 50 percent in Canada, and 30 percent in Portugal.93

This raises the possibility that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is seasonal. Last year, a meta-study of coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV-2 found that they typically peak in the Northern Hemisphere during the winter, with the most common peak months being January and February. “The apparent seasonality of human coronaviruses across the globe suggests that this phenomenon might be mined to produce improved understanding of transmission of COVID-19,” the authors concluded.94

The notion of seasonality is both obvious and mysterious. We know that many respiratory viruses are less virulent in the summer, accelerate in the closing months of the calendar year, and then recede as the days grow longer after December. But as the Harvard epidemiologist Michael Mina told New York magazine, “We don’t fully appreciate or understand why seasonality works.”95